It is worth reflecting on Jan Apelqvist’s recent editorial, which outlined the evidence that supports the role of the multidisciplinary footcare team and the optimal components of a preventative footcare programme. The newly launched Second International Consensus Document (Schaper et al, 2007) and The Diabetic Foot Journal’s own consensus documents all provide a sound rationale for best models of practice. There are many other reviews, position documents and national and international guidelines that have impacted on practice and made a measurable difference to the diabetic population. It is inappropriate to name them all, but the international consensus on the diabetic foot has arguably had the biggest impact in global terms (Boulton et al, 2005).

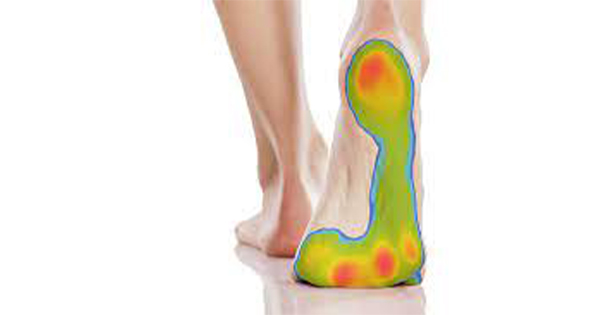

In an interesting report from Stephen Morbach (2006), who is Chairman of the Diabetic Foot Study Group of the European Association for the study of Diabetes (EASD) he makes the point that there is evidence of both success and failure with the implementation of a multidisciplinary footcare team across Europe (Holstein et al, 2000; Van Houtum et al, 2004; Trautner et al, 2001). The identification of the reasons for success and failure requires close scrutiny. The influence of healthcare organisations and reimbursement in prevention and management of the diabetic foot ulcer should not be underestimated (Boulton et al, 2005). In his report, Stephen Morbach describes the success in Denmark, where the amputation rates have decreased by 40 % (from 1982–93) and where Danish people with diabetes are reimbursed for most of their payments for special shoes, insoles and their visits to the podiatrist. In addition, it is estimated that adequate treatment is available for up to 75 % in a multidisciplinary setting.

This contrasts with the picture in France where podiatric care is poorly reimbursed and only 20 % of diabetic patients are screened for neuropathy. In Germany, high amputation rates have been published, despite the widespread approach of multidisciplinary departments. However, less than 20 % of diabetic patients with foot problems are referred to the specialist clinics from primary care. As a result of the lack of common structure of diabetic foot care across Europe, the founding of the Eurodiale consortium has evolved and may well provide very useful data for a European consensus. There may be some very useful lessons to be learnt from our European neighbours, including the significance of reimbursement, the importance of insole and footwear provision and the requirement for structured podiatry services. What about the situation in the UK?

In every locality throughout the UK, there are multidisciplinary foot clinics that include members from the following professions: podiatrist, diabetes nurse, diabetologist, angiologist/intervention radiologist, vascular surgeon, microbiologist, orthopaedic surgeon, orthotist and shoemaker. In addition, every district has a structured preventative programme that includes appropriate screening, allocation of risk status, structured referral pathways and an education programme with complete diabetes data sets for comprehensive audit and evaluation. You may not recognise this scenario.

Whilst every reader of this journal will probably advocate the described foot service above, it is unlikely that it is common practice. However, I am aware of a number of centres in Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland that do come very close to the ideal suggested. Perhaps if the ideal structured diabetic foot services had been in place before the latest round of NHS reforms and practice-based commissioning, we would have less to fear. I suspect that those primary care trusts that have less-well-organised foot services will have more to be concerned about regarding their future.

Many of you may receive the Practical Diabetes International journal. There is a relatively new item titled What’s It Like in My Patch? (Gossage A, 2007) that calls for all diabetic healthcare professionals to write in and describe their situation in the light of the current state of the NHS. It is abundantly clear that there are major differences in the way that diabetes services are delivered. It may be timely to make a similar request to The Diabetic Foot Journals’ readers to help determine the current situation throughout the UK.

Whilst there are several helpful documents to help shape diabetic foot services and the commissioning of diabetes services; for example, the national minimum skills framework for commissioning of footcare service for people with diabetes (FDUK, 2006), the diabetes NSF delivery strategy (DoH, 2003), the diabetes commissioning toolkit (DoH, 2006a), the diabetic foot guide – national diabetes support team (DoH, 2006b) and the diabetes national workforce competence framework guide (Skills for Health, 2004), there remain concerns about the future for diabetic foot services and their patients.

The main area for concern is the possible fragmentation of the hospital-based multidisciplinary footcare team and the subsequent quality of care for these patients with active foot lesions. However, how many multidisciplinary footcare teams are in operation in the UK? It would be really useful to determine the current situation in order to audit and evaluate before the impact of the reforms occur. Otherwise, we will have little evidence to defend our current practices.

The right Hon The Lord Morris of Manchester AO QSO is the current president of the Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists and has been a great ally of the podiatry profession. On 8 May, 2007, he asked her Majesty’s Government whether or not they have any plans for ensuring urgent access to podiatric care for diabetics, irrespective of where they live, under the National Health Service.

In the response from Lord Hunt, he indicated that it was up to primary care trusts in partnership with local stakeholders to determine how best to use their funds to meet national and local priorities for improving health. Lord Hunt referred to the NSF for diabetes (DoH, 2003) and the national diabetes support team diabetic foot Guide (DoH, 2006b) that would aid the commissioning process.

It is heartening to read of the prominence of the multidisciplinary footcare team as examples of gold standard care throughout the diabetic foot guide. It is of paramount importance for those charged with the commissioning process to avail themselves of the key documents and make the right decisions. On further reflection, it appears that where there is a multidisciplinary footcare team, there is inevitably a dedicated consultant physician. The diabetic population should not have to rely upon those few heroes. There really ought to be appropriate, robust systems in place.

Perhaps Gordon Brown who has made the NHS his priority on the domestic front will indeed listen both to patients and to healthcare professionals up and down the country. He has been on record to state that access to healthcare services must be improved upon. This will be welcome news for those diabetic patients who develop limb-threatening infections. The diabetic foot community need to make it absolutely clear that we know what works and what is required. It is not the time to dismantle good practice. However, it is the time to improve suboptimal practice. Is diabetic foot care a post code lottery? Can you access bespoke footwear for your patients?

Let us know what the current situation is in your area.