Few qualitative studies examine the perceptions of foot complications among people with diabetes. The research that is available on the topic focuses on the perceptions of people with existing or previous foot ulceration (Ashford et al, 2000; Hjelm et al, 2003; Searle et al, 2005; Gale et al, 2008) with little information available on the perceptions of people newly diagnosed with diabetes. If early preventative interventions are to be successful, it is important to understand people with diabetes’ thoughts and beliefs about feet and foot care soon after diagnosis.

This study examines the perceptions of diabetic foot disease among people newly diagnosed with diabetes. The participants’ knowledge of diabetic foot ulceration – causes, management and complications – as well as their knowledge of self-care of the foot, were explored during a small focus group discussion.

Methods

A qualitative research approach was used and an interview schedule developed (Box 1). Participants were selected via quota and snowball sampling methods to take part in digitally recorded focus groups lasting approximately 45 minutes.

Inclusion criteria

Participant inclusion criteria were:

- Type 1 or 2 diabetes.

- Diabetes diagnosis within the preceding 6 months.

- Aged 18–65 years.

- Had attended their first diabetic foot screening appointment with a podiatrist where they would have received information regarding diabetic foot complications and advice on self-care.

- Able to give written consent.

Due to limited resources, people who met the inclusion criteria but could not speak English, or had a mental health issue or communication or behavioural difficulties were excluded.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh and also via the integrated research application system with Sunderland Research Ethics Committee.

Analysis of data generated

Interviews were transcribed and analysed using interpretive phenomenological analysis to identify emergent themes.

Results

Eight people agreed to attend the focus group; 4 people cancelled on the day. One focus group comprising four participants was conducted. Table 1 summarises participant demographics.

Beliefs about illness and consequences of disease

Two participants had very poor knowledge of the impact of diabetes on the foot. This was evidenced by responses to the question: What impacts of diabetes on your feet are you aware of? Participant 1 said: “No not any … something like numbness, innit?”, while Participant 2 reported “None whatsoever”. However, these responses were at odds with later responses from these two participants that indicated more knowledge than was initially volunteered. By comparison, Participants 3 and 4, respectively, provided somewhat more comprehensive answers: “Numbness, gangrene, ulcers. You can get ulcers on your feet”; “Cellulites for one … you can end up losing your limbs.”

One comment highlighted confusion in Participant 2 about their diabetes. Participant 2 – despite a clinical diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in his medical notes, having attended his diabetic foot screening appointment with a podiatrist and agreeing to participate in the focus group – stated that he was not sure whether he had diabetes or not.

Most (3/4) of the participants believed diabetic foot ulceration to be caused by internal factors (e.g. neuropathy). Participant 4 was also able to identify internal and external factors (e.g. trauma) as contributing to ulceration: “Don’t go bare foot in the garden as people have done and stand on nails [laughs, implying an ulcer-inducing accident experienced by her husband who has diabetes and a history of ulceration].”

Psychological and social impacts

Three participants exhibited negative emotions when describing diabetic foot disease, in particular reduced mobility, peripheral sensory loss and pain. Comments included: “Numbness, which is horrible to feel … [neuropathic pain] is terrible because pain killer doesn’t take it away and it’s like electric shocks” (Participant 4); “Yes, I’m worried about mobility problems in the future” (Participant 3).

Anxiety and fear regarding foot ulceration and amputation were expressed by three participants. The participant who had experience of foot problems (through an effected family member) expressed more fear and anxiety than those without related experience. Participant 4 said: “My husband [had a diabetic foot ulcer]. It was terrible … we all thought he’d lose his foot and so much of his leg … you could see the bone in between his toes! You can end up losing your limbs. It scares me”.

The negative impact of diabetic foot complications on family members and relationships was also described by Participant 4: “They [people at risk of ulceration] don’t realise how the family feel. What they are doing to themselves. He didn’t have his slippers on [when an accident occurred that precipitated ulceration]”.

Health-seeking behaviour and self-care attitudes

All participants said that they were more concerned by other complications of diabetes, rather than those related to the foot. Participant 2 said: “You know, I’ve got that many problems in my body that [my] feet are the last thing I think of. I have problems with [my] heart, kidneys”.

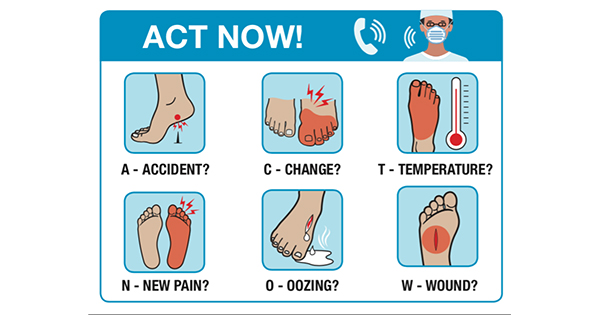

Although participants were able to suggest some aspects of diabetic foot complications, knowledge of self-care behaviours was poor and participants were vague regarding adherence. When asked to describe methods of foot ulcer prevention, Participant 1 said “Clean them, innit?”, while Participant 3 suggested “Hygiene, look for infection”. Only Participant 4 was able to give a more comprehensive response (to which she reported to adhere): “Comfortable shoes … never tight squeezing feet, in case that does a lot of damage … check toes, cracks in feet … nails need to be kept short and checked regularly”. Furthermore she understood that if there were any problems to seek immediate medical help.

Participant 3 reported that he had previously acquired a foot wound, sustained after tripping while walking barefoot. The wound was managed at home. The participant failed to recognise that the injuries sustained while walking barefoot could be the precursor to ulceration. Nor did he concede that any self-care practices could have prevented the event; when asked how the wound came about, he stated: “Well I’m diabetic, so I guess that’s what happened”.

Perceptions of healthcare professionals and the system

Participants’ perceptions of healthcare professionals were generally positive. Participant 4 said: “Well they’re very good up here … they check your nails, your feet, they do the test”. Participant 3 said: “The information and material given is good”, but went on to say “I rang the surgery reception for feet pain … and nobody seemed to put me through to anyone”.

Discussion

Positive foot care behaviours, such as attendance of podiatry appointments, use of foot creams and adherence to approved footwear, can reduce the risk of foot ulceration (Suico et al, 1998). Thus, an appreciation of, and adherence to, self-care behaviours is key to ulcer prevention.

Experience in clinical practice and reports from the literature suggest that people with diabetes do not routinely adhere to self-care recommendations (McNabb, 1997; Armstrong et al, 2003). Reasons for non-adherence are complex, however it has been postulated that patients’ beliefs about their condition may influence their adherence to self-care practices and could affect help seeking behaviour (Vileikyte et al, 2001). It is, therefore, important to determine how patients with diabetes perceive and understand foot ulceration.

Knowledge about diabetic foot disease and self-care of the foot was variable in this small cohort of people with recently diagnosed diabetes. Some participants recognised that the possible consequences of diabetes for the foot included neuropathy, infection, ulceration and amputation. Participants believed that ulcers mainly arose as the result of internal factors, such as neuropathy and poor glycaemic control. Only one participant identified that external factors, such as trauma, also play a role in ulceration.

The most informed participant in the present study was able to identify diabetes-related foot problems and suggest a range of self-care behaviours for ulcer prevention. This participant had second-hand experience of diabetic foot disease having supported her husband with a history of foot ulceration. Her higher-level understanding of the causes and consequences of diabetic foot disease supports Tessaro et al’s (2005) findings that those with diabetes know little about the diabetic foot before diagnosis unless a family member has the condition.

One participant reported a foot injury, although failed to recognise that any self-care practices could have prevented the event, or that the event could have resulted in ulceration. This participant’s experiences and beliefs are consistent with Gale et al’s (2008) findings that the perception among their cohort with diabetes was that minor foot injuries were not of particular consequence and not potentially ulcerative. The participant’s feeling that he could not have done anything to avoid or prevent the wound is reflected by the findings of Hjelm et al (2003) who found that people felt that their diabetic foot ulcers were out of their own control. Snoek et al (1999) described that this kind of cognitive attitudinal impediment – not a lack of information or ability – is frequently the main barrier to good self-care.

Interestingly, one participant reported being unsure as to whether he had diabetes – despite a clinical diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in his medical notes, having attended his diabetic foot screening appointment with a podiatrist and agreeing to participate in the focus group. This may partially be explained by Peel et al’s (2004) finding that patients reported that their GPs were unwilling to deliver a definitive diabetes diagnosis. Given an uncertain diagnosis, these patients displayed increased anxiety and were unwilling to adapt their lifestyle to incorporate suggested self-care measures.

Most of the participants expressed that their feet were the least of their worries. This is supportive of previous studies

where participants reported that diabetes diagnosis is followed by large volumes of information on all body systems. Thus, advice regarding complications of the feet and their care tended to be considered peripheral (Searle et al, 2008).

Anxiety and fears regarding foot ulcers and amputations were also central themes, as they were in previous qualitative studies (Ashford et al, 2000; McPherson and Binning, 2002; Hejlm et al, 2003; Searle et al, 2008). Mobility concerns were also highlighted as an area of concern (Ashford et al, 2000; McPherson and Binning, 2002; Hejlm et al, 2003).

Limitations of the study

Caution needs to be taken when drawing conclusions based on the results presented here. Only four people participated in this study, making the sample population too small for the results to be confidently considered to be representative of the wider population with diabetes. There was a preponderance of male participants. All participants were white British, English speaking in origin; minority ethnic groups and patients from other areas were not represented.

The interviewer was also a podiatrist, which may have affected participants’ responses. An independent interviewer would have limited such bias.

Conclusion

This explorative study suggests that, although people newly diagnosed with diabetes knew of diabetic foot ulceration, the majority were unsure what this was and knowledge of causes and consequences of this was limited. Overall, participants believed that diabetic foot ulcers were due to internal factors and recognition of external causes was limited, therefore participants perceived that foot ulcers could not be prevented. Participants who had previous experiences of foot ulcers contributed a broader discussion compared with those with no experience. Participants tended to perceive that their feet were the least of their worries given other health concerns.

This study examined the views of people newly diagnosed with diabetes, which is the first of its kind to the authors’ knowledge. The person with diabetes’ perceptions of their condition and associated complications can influence adherence to treatment and care-seeking attitudes, and therefore should be taken into account when devising care plans.

Qualitative studies examining the perceptions of foot complications among people with diabetes is in its infancy. This gap in the research needs to be addressed to provide a more holistic approach to preventative self-care of the diabetic foot.