The recently published guidelines for type 2 diabetes, prevention and management of foot problems were developed by the National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (NICE, 2004) and will be welcomed by many practitioners involved with diabetic foot care.

The rigorous approach that NICE have adopted in developing the guidelines include: acknowledged expert advisory groups, systematic review of evidence, peer review, and a grading scheme that ranks the quality of the evidence that underpins the guideline recommendations. The effectiveness of the NICE guidelines will depend on the following:

- Validity, reliability, relevance and flexibility.

- Cost-effectiveness/resource implications.

- Dissemination, implementation and regular review.

The guidelines’ layout has to be applauded; there are clearly defined sections, clarity and clear indication of the nature of evidence that they were developed from. A couple of the recommendations may be rather unrealistic in terms of resource implications, but that is hardly surprising given the nature of existing diabetes foot services throughout England and Wales. There is some ambiguity surrounding the nature of the ‘foot protection team’ and the guidance regarding foot care education.

Few would disagree with the key priorities for implementation. My only criticism is the omission of any imperative to record and store data on an appropriate diabetes database. I note the inclusion of Appendix D about technical detail on the criteria for audit, which is contained in the National Diabetes Audit and in the GP contract. Perhaps my concern is unrealistic, but unless we record standardised valid data, we will continue to struggle to provide meaningful evidence of any improvement of our service. The implications of annual review, regular review (3–6 months) and frequent review (1–3 months) for the different risk group categories suggested, will place a very high demand on existing services. There will have to be significant changes in the way diabetic foot services are organised and resourced in order to deliver this guideline. However, the guideline may provide some leverage to squeeze additional resources from the local health communities.

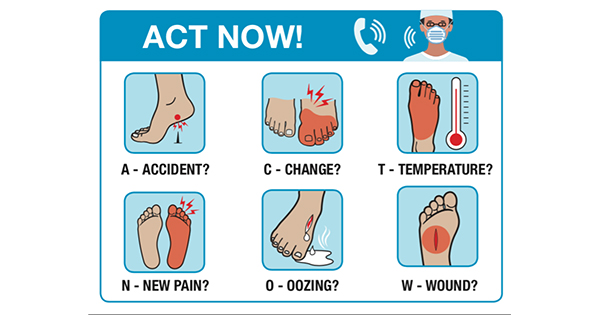

Several guidelines are dedicated to foot health education and patient behaviours, a dramatic improvement on past guidelines that have often neglected this key topic. It brings into sharp focus the outstanding need to identify best practice if we are to prevent and reduce the burden of morbidity of the diabetic foot ulcer. A statement in guideline 1.1.1.11, ‘Use different patient education approaches until optimal methods appear to be identified in terms of desired outcomes,’ sums up the paucity of our knowledge of best practice. There is abundant evidence from the document that the experts are aware of the issues surrounding foot care education. Guideline 1.1.1.9 states that structured patient education should be made available.

A more contentious guideline (1.1.6.11) suggests that ‘for patients with foot ulcers or previous amputation, healthcare professionals could consider offering graphic visualisations of the sequelae of disease, and providing clear, repeated reminders about foot care.’ The use of scare tactics should be carefully evaluated, as some key research findings indicate that they can have undesirable outcomes.

Section 1.1.6, ‘Care of people with foot ulcers’ contains guidelines that will depend on the existence of care pathways and a recognised multidisciplinary foot care team. It is suggested that ongoing care of an individual with an ulcerated foot should be undertaken without delay by a multidisciplinary foot care team. The subsequent guideline explicitly describes the members of the team, which can only really be based in the secondary hospital setting. I suspect that many healthcare professionals working in primary care may not entirely concur. It may be that the authors have used the term ‘ongoing care’ to be interpreted broadly and do not intend to exclude the concept of shared care between the primary and secondary sectors.

‘Implementation in the NHS’ (section 3) has general comments about the resources and timelines required. The implementation will build on the NSF for Diabetes and the Diabetes Information Strategy in England and Wales and should form part of the development plans for each local health community in England and Wales.

Conclusion

Guidelines are only as effective as those who resource, implement and evaluate them. The debate on models of care and best practice will continue. The NICE guidelines cannot afford to be ignored. We now have an important, valid document that can be used as a national benchmark for diabetes foot services, and healthcare professionals are expected to take it fully into account when exercising their clinical judgement. With the increase in litigation, it may be judicious for clinicians to reflect on their current practices using the document, as it could be used in the courts against them!