The diagnosis of diabetes is a significant event in a person’s life. This article will explore the varying reactions to diagnosis, and how an understanding of the grief process can help us appreciate both the psychological impact of a diabetes diagnosis and how we can help people to accept it. It will also support the reader to understand those individuals who have been diagnosed for some time but may still be “denying” or struggling to come to terms with the diagnosis.

What people with diabetes say about their experience of diagnosis

The following quotes are from people on the diabetes.co.uk forums:

- “First came the fear, followed by the anger – and finally the curiosity.”

- “I’m feeling totally overwhelmed by it all, to be honest, I feel guilty and ashamed that I have it, and can’t even begin to contemplate spending the rest of my life counting blood sugar numbers.”

- “The guilt just eats away at me.”

- “I’m constantly living with the fear that I’ll end up going blind, or having a limb amputated, or something else, due to the diabetes.”

- “I see the worry and stress on my husband’s face, and it literally breaks my heart every time. I feel awful for being the cause of his stress.”

- “I remember being quite relieved when I was diagnosed with diabetes, like somehow I knew I had it, and I welcomed the answer to why I had been feeling so ill for the last few months.”

Accepting the diagnosis is a process, not an event

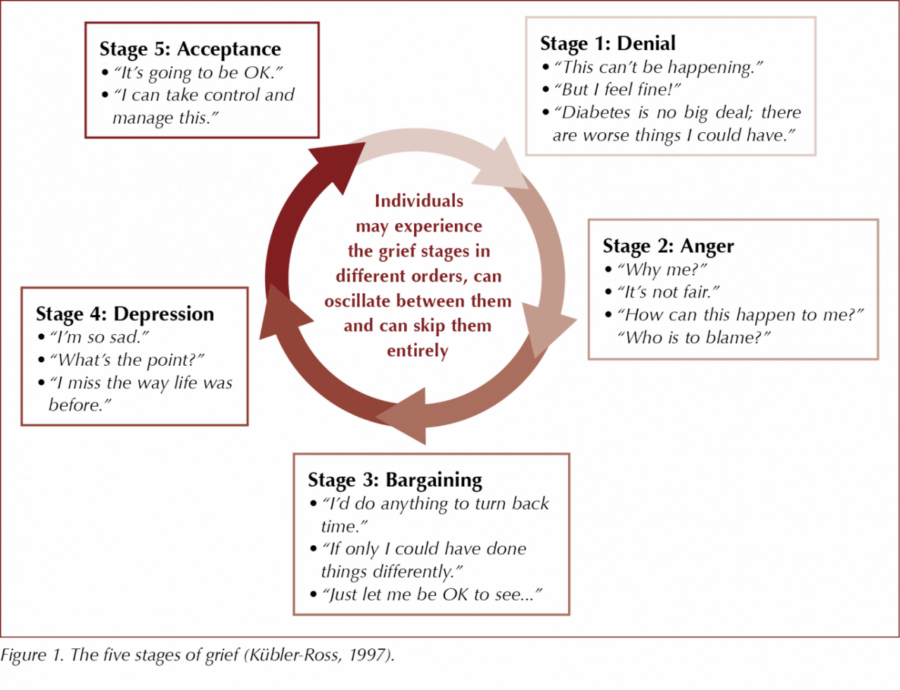

Many studies into the effects of being diagnosed with a chronic health condition have likened it to the grieving process (Kübler-Ross and Kessler, 2005). There can be a mourning for the loss of health and wellbeing. In the same way as grieving, dealing with a diagnosis is therefore a process, not an event. The five stages of grief (Kübler-Ross, 1997) provide a valuable framework for understanding the impact of the diagnosis (Figure 1).

The grief cycle has been offered as a framework to better understand the diagnoses of many long-term health conditions, including diabetes. Whilst there may be differing views of the value of using such a model, it can certainly enrich our understanding of the range of reactions towards diagnosis.

Although depicted as a cycle with stages, individuals experience grief differently, often skipping stages or oscillating between them. In a similar way to grief, which can persist for a long time, people with diabetes can move between stages over years, occasionally decades. Sometimes, the people we care for may never truly accept their diagnosis. Family members can also experience reactions in this way.

By becoming aware of the feelings your patients have towards their diagnosis and recognising which stage of the process they are in, you can help them to manage the potential difficulties better.

Stage 1: Shock and denial

The experience of being diagnosed is a significant life event – there is a sudden awareness that life has its limits. Numbness, confusion, fear, blame and avoidance are all natural responses to this news. It is likely an individual is in this stage when we hear these kinds of reactions:

- “Diabetes is no big deal; there are worse things I could have.”

- “But I feel fine!”

- “Why bother to care for it? I’ve got to die of something someday.”

Denial can be a healthy defence mechanism. It functions as a defence after unexpected news. It allows the person to collect themselves and, with time, come to terms with the event. Denial is often conceptualised negatively, but psychologically it can play an important role in the short term, defending against the painful feelings of this new reality. Being able to put diabetes in its own compartment for a time allows one to get on with life, and is a way of gaining back some control, until the individual can get used to the idea of having the condition. But while there can be some positive elements to denial, over the long term the negative aspects outweigh the possible benefits, and people who continue to use denial as a way of coping tend to have poorer diabetes health than those who do not (Polonsky, 1999).

Stage 2: Anger

Shock and denial can be replaced by feelings of anger, rage, envy and resentment. The obvious question for the person is often “Why me?” This stage can be challenging as the anger is often displaced onto others, such as health professionals and family members. Although not pleasant to be on the receiving end of, anger is a natural human emotion. The encouragement is to try not to take it personally or get defensive, although this is easier said than done! Ask what you can do to help and look for ways you can help the person feel more in control of their condition.

Stage 3: Bargaining

“I’d do anything to turn back time” “If only I could have done things differently’” “Just let me be OK to see…” “If only…” and “what if…” thoughts. Those with religious/spiritual beliefs may pray, “Please God…”

These kinds of daydreaming and bargaining statements can offer some reprieve from the pain of anger. Guilt and regret are likely to be felt at this stage. Reminding people that there are many factors that can contribute to developing diabetes can help them not to be overwhelmed with guilt.

Stage 4: Depression

“I’m so sad.” “What’s the point?” “I miss how life was before diabetes.” Different from the clinical term of depression, this stage of the acceptance journey could be, paradoxically, a sign of progress. It demonstrates that the person understands the certainty of the diagnosis, which is essential for resolution and progression. There can be a sense of hopelessness but, like grief, it usually will pass.

It can be tempting to try and encourage the person to cheer up or not to be sad. However, if the person can express their sorrow to an empathic listener, acceptance is much easier. If it persists, make use of depression screening questions and refer for mental health support.

Stage 5: Acceptance

“It’s going to be OK.” “I can take control and manage this.” Acceptance indicates that the person has come to terms with the diagnosis; however, it should not be mistaken for a happy stage necessarily! Although diabetes will usually remain an unwelcome visitor to life, it can become a part of the person that can be cared for, rather than a stranger to be dreaded or battled against.

The importance of the diagnosis conversation

Although just a routine part of the primary care professional’s working day, the diagnosis conversation is pivotal, as it sets the scene for the person’s relationship with their diabetes. We model how important (or not) diabetes is by the things we say and the way we say them. Contrast the way that a diabetes diagnosis is delivered in healthcare settings compared to a diagnosis of cancer or HIV. If the health professional does not seem concerned, for some patients this can act as a model and encourage their own lack of concern, and therefore lack of activation to engage with their diabetes.

The diagnosis conversation impacts clinical outcomes

A link has been demonstrated between the type 2 diabetes diagnosis conversation and clinical outcomes (Dietrich, 1996). The reaction/attitude that healthcare professionals displayed towards patients at the point of diagnosis was critical in influencing their attitude towards the perceived seriousness of the condition and, consequently, their ability to self-manage.

A stance of clarity is important. People with diabetes often report that they are not clear whether they actually have a diagnosis of diabetes (Jarvis and Rubin, 2007). They may have been told they have “borderline” diabetes or are “tipping into” diabetes. This is equivalent to telling a woman she has a “touch of pregnancy”. It is important that we be clear in our communication.

Polonsky et al (2010) investigated people’s experiences at diagnosis and their diabetes-related distress and self-management efforts 1–5 years later. Clinical outcomes were significantly better among those who reported that they had:

1. Been reassured at diagnosis that diabetes is both serious and can be managed successfully.

2. Been instilled with a sense of hope.

3. Developed a clear action plan with their healthcare provider.

How to provide support

Aim to convey a sense of both seriousness and optimism. Communicate that diabetes is a serious condition while reassuring that it can be managed successfully: “It’s important that you know that diabetes is a serious health condition. The good news is there are lots of treatment options available to manage it, so if we work together, there’s no reason why you can’t live a long and healthy life with the condition”.

Convey a sense of hope that they will learn to manage their condition with time. Give information about diabetes to take away, taking into account the appropriate amount, type and medium tailored to the individual’s preferences. This is perceived as emotionally supportive, and the person will be able to access the information when the time is right. Develop a clear action plan for their next step – their next appointment, a referral for education, signposting to Diabetes UK peer support services, and so on.

Supporting people who may be “in denial”

Denial is a protective response to news that is difficult to take in and can often persist for many years. However, if the person has attended their appointment with you, they arguably are not in complete denial! A suggested question is: “I understand diabetes isn’t the most important thing to you right now. We’ve got a few minutes to think and I’d be keen to know, what is important to you right now?” Listen and be empathic, interested and curious. Once the patient has finished, you could ask, “I’m just wondering how diabetes may impact [the priority they’ve just spoken about] in the long term? I’m here to support you, whenever you’re ready.”

The person may not have a ready response to this question, and it isn’t likely to transform denial immediately, but it is likely to be a more useful question than simply reinforcing health education messages if that approach has already not led to behaviour change.

Helpful responses from the health professional

- “This is a lot to take in.”

- “This is hard news to hear.”

- “This is a big life event and you are likely to feel a range of emotions in the days to come.”

- “It’s OK to feel the way you do.”

- “You have a right to feel upset about this news.”

- “Although these feelings might not feel normal to you, they are natural response to receiving this news.”

- “You might experience tears, anger, being more short-tempered than usual, feeling more anxious and lower in mood. This is very usual.”

Conclusion

Every individual diagnosed with diabetes is unique, and therefore every reaction to a diagnosis conversation will be a unique one. This article has explored the psychological impact of diagnosis and how we can support people to navigate the journey of diagnosis. Diabetes is a medical condition, yet diagnosis brings with it an emotional response – for both individuals involved in the conversation. There is growing evidence that if health professionals can create a space in our medical settings to focus on the emotional impact of diabetes, improved clinical outcomes can occur (Alam et al, 2009). Supporting the newly diagnosed person in the ways outlined in this article can contribute towards savings in the long-term – whether that be clinical time, NHS spend or emotional and physical wellbeing over a lifetime.

The mortality benefits of smoking cessation may be greater and accrue more rapidly than previously understood.

2 Apr 2024