Bone fragility and fractures are emerging as an important, common and severe complication of diabetes (Hofbauer et al, 2022). The possibility that bone changes associated with diabetes are related to microvascular effects were previously discussed in a review in the same journal in 2017, but with little clinical impact (Shanbhogue et al, 2017). People with type 1 diabetes have reduced bone mass and strength, while bone mass is normal but fragility increased in type 2 diabetes. There is a 32% increased relative risk of fracture in those with diabetes compared to those without diabetes and, as with many complications, a higher relative risk of 1.51 in those with type 1 diabetes compared to 1.22 in those with type 2 diabetes. The hip fracture relative risk is as high as 4.23 in those with type 1 diabetes and 1.27 in those with type 2 diabetes, compared with those without diabetes. People with type 1 diabetes also have a doubling of risk of atypical femoral fractures, even if they have not had bisphosphonate treatment, which usually predisposes to these fractures. Men with type 2 diabetes have a higher risk of fracture at all sites than women, and people with obesity and type 2 diabetes have more injuries than those without diabetes, which may partly result from neuropathy and retinopathy.

In people with diabetes, hip-fracture risk is five times higher in those who have previously had any fracture. As well as the conventional fracture risk factors, such as low bone density, family history of fractures, increasing age and female sex, falls are a significant risk factor, more common amongst those treated with insulin and sulfonylureas (SUs) who develop hypoglycaemia, those with neuropathy, vitamin D deficiency, wide glucose fluctuations and sarcopenia.

The FRAX calculator, with or without inclusion of bone mineral density (BMD) data from DXA scanning, is used to estimate 10-year risk of any fracture and hip fracture. The absolute fracture risk in people with type 2 diabetes has been calculated to be 30–50% higher than that predicted at each level of BMD or FRAX score. As a result, osteoporosis should be diagnosed at a T-score of –2.0, rather than –2.5 in people with type 2 diabetes. Four adjustments to FRAX inputs may improve predictive accuracy and treatment thresholds, including adding rheumatoid arthritis as a marker of inflammation, a trabecular bone score adjustment, decreasing measured femoral T-score by 0.5 standard deviations or increasing age by 10 years.

According these experts, there is no evidence that DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 RAs or SGLT2 inhibitors have detrimental effects on bone metabolism (despite early concerns with canagliflozin in one study), and metformin has neutral or positive effects. SUs and insulin may increase fractures through hypoglycaemia and falls. Thiazolidinediones increase fracture risk from 12–14 months into treatment, due to increasing adipocytes and decreasing osteoblast precursors in bone marrow. Non-vertebral fracture rates overall are 30% higher compared to those without diabetes, and double in those treated with insulin.

Potential mechanisms

People often develop type 1 diabetes prior to achieving peak bone mass, and it is likely that lack of insulin’s anabolic effects reduces achieved peak bone mass.

Bone remodelling by osteoclasts and osteoblasts is important for normal bone repair. High glucose/HbA1c levels reduce bone formation and osteoclast function, resulting in low bone turnover, and there is an increase in adipocytes at the expense of osteoblasts in bone marrow. There is a pro-inflammatory state, and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) accumulation makes collagen in bones stiffer and less resistant to fracture. Poor microvascular supply appears to cause hypoxia and cortical porosity, which can be seen on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT.

So what can we do?

Increased bone fragility increases with disease duration. People with type 1 diabetes may have bone loss at an early age and have an increased fracture risk throughout life.

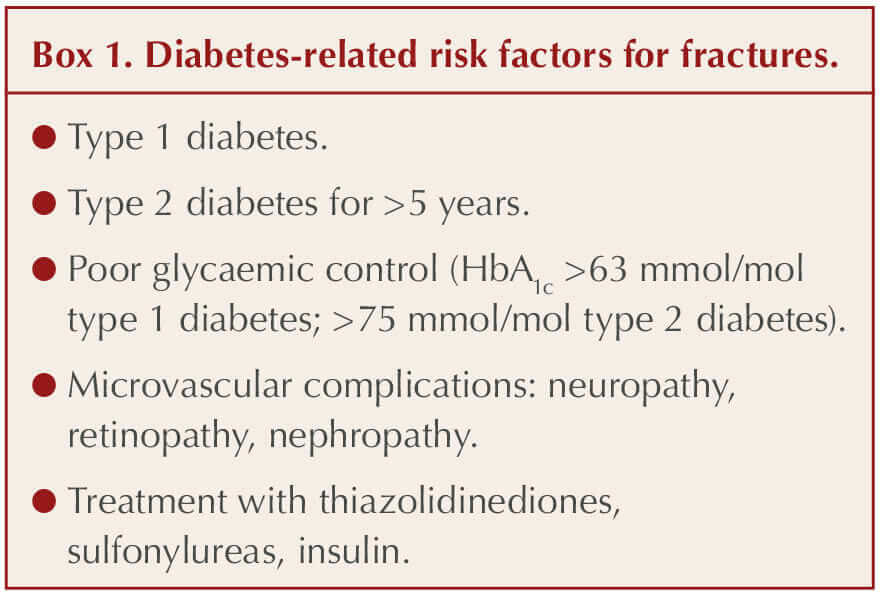

● Assess diabetes-related risk factors for fracture (see Box 1).

● Consider specialist support/multidisciplinary input for those at highest risk of falls and fractures, including those with neuropathy, retinopathy, nephropathy, peripheral vascular disease and gait abnormalities.

● Poor glycaemic control (HbA1c >63mmol/mol in type 1 diabetes, >75 mmol/mol in type 2 diabetes) is associated with high bone fragility and fractures. Aim for good control using drugs that do not increase hypoglycaemia or have detrimental impact on bone.

● Consider vitamin D measurement (or supplementation) in those at risk of falls and fractures or in care homes.

● Undertake bone assessment in type 2 diabetes after 5 years, including: risk factor assessment; FRAX with adjustments; evaluation of vertebral fractures with X-ray or during DXA scan; and measurement of BMD using DXA scan. A correction factor of –0.5 for the BMD result is recommended in those with diabetes, so it is important to notify the scanning unit when referring people with diabetes. Repeat DXA scan after 3–5 years, if low fracture risk.

● Rapid bone loss and increased fragility fracture risk occurs after bariatric surgery, so 2-yearly DXA scan recommended.

● Ensure age-adjusted protein, calcium and vitamin D intake. Accompany weight loss with resistance and endurance physical activity training, which can improve glycaemic control, prevent sarcopenia and reduce falls.

● Consider vitamin D supplementation (400–800 IU daily) if 25(OH) vitamin D level <20 ng/mL (higher doses if obesity and malabsorption) and calcium supplementation if dietary intake <1.2 g/day.

● There is limited evidence for commonly used osteoporosis therapies in those with diabetes. Since bone turnover may be low and many people with diabetes will have low eGFRs making them unsuitable for some therapies, specialist guidance should be sought, although recommendations for conventional bone therapies are provided in this review. Anabolic agents, such as teriparatide, may be most effective in those with previous fractures.

● Following surgical fracture treatment, post-operative complications, such as wound infections and delayed or non-union of fractures, are commoner with diabetes. Mortality following hip fracture is 28% higher in men and 57% higher in women with diabetes versus those without. Longer admissions and detrimental impact on diabetes control and sarcopenia are likely in survivors.

Click here to read the study in full.

The mortality benefits of smoking cessation may be greater and accrue more rapidly than previously understood.

2 Apr 2024