Although it has been known for some time that cardiovascular mortality rates in people with and without diabetes have been declining, this is the first study to explore how this has changed the composition of the mortality burden in those with diabetes. The study used the well-validated UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) primary care database, which is representative of the English population, to identify 313,907 people with diabetes who were compared in 1:1 proportions with age- and sex-matched controls without diabetes from the same database. Links to the Office for National Statistics database provided mortality data. The authors estimated annual overall mortality rates and those from 12 specific causes in people with diabetes and compared with rates in those without diabetes.

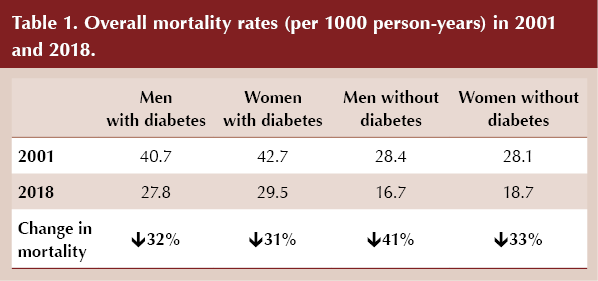

Overall mortality rates declined in both populations, and cause-specific deaths decreased in 10 of 12 conditions studied, most markedly for ischaemic heart disease and stroke. All-cause death rates declined from 40.7 to 27.8 per 1000 person-years in men with diabetes, and from 28.4 to 16.7 per 1000 person-years in men without diabetes (a decline of 32% and 41%, respectively). Key data from the study, including comparison of mortality rates between those with and without diabetes, are summarised in Table 1 and Table 2. Mortality rates from dementia and liver disease increased in those with and without diabetes, but the increases in people with diabetes were greater. Cancer deaths decreased in both groups but the reduction was smaller in those with diabetes.

|

|

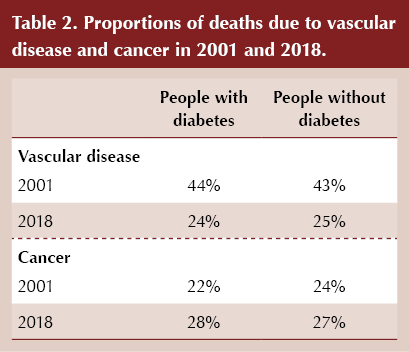

The proportion of deaths due to vascular disease fell from 44% in 2001 to 24% in 2018 in people with diabetes, while the proportion due to cancer increased from 22% to 28%. Falls in vascular death rates were slightly smaller in those without diabetes, and although the proportion of cancer deaths increased by less in those without diabetes, cancer still accounted for a greater percentage of deaths than vascular deaths in both those with and without diabetes.

The absolute gap between overall mortality rates in those with and without diabetes was broadly maintained between 2001 and 2018 (excess deaths per 1000 person-years fell from 12.3 to 11.1 in men with diabetes, and from 14.5 to 10.8 in women with diabetes). When men and women were combined, in 2001 the gap in cause-specific death rates between those with and without diabetes was greatest for ischaemic heart disease, diabetes and stroke, but by 2018 cancer mortality was responsible for the largest percentage of the diabetes-related death gap.

People with diabetes are nearly twice as likely to develop liver or pancreatic cancer and significantly more likely to develop other “diabetes-related cancers” (gall bladder, endometrium, colorectal and breast) than people without diabetes (Song, 2021). In this paper, mortality rates for “diabetes-related cancers” and “other cancers” were collected and reported separately. Cancer mortality in the period from 2001 to 2018 declined both in people with and without diabetes, but at a much lower rate in those with diabetes compared to those without. The diabetes-associated gap in death rates declined significantly for ischaemic heart disease and stroke but increased for dementia, other cancers and diabetes-related cancers.

The authors attributed the decline in vascular mortality to improvements in behaviour change (e.g. smoking, cholesterol and salt consumption); prioritising those with diabetes for preventative measures, including incentivisation by the Quality and Outcomes Framework; and treatments improving survival rates in those with vascular disease. They suggested that the increase in liver disease mortality could be attributed to obesity and high alcohol consumption but could be more complex.

Risk ratios of 1.25 for autism spectrum disorder and 1.30 for ADHD observed in offspring of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy.

18 Jun 2025