“Silo working has been a disaster,

Too specialised to care,

About the PWD,

Who in despair,

Travelling between hospitals,

Wasting taxi fare.”

– Anonymous

One of the constants in the NHS since its inception has been the cyclical change in terms of service delivery management. In this process, we have often failed to consider the changing needs of the “patient”, and certainly relevant to this is the healthcare journey for people with diabetes and their families and carers. However, with every change comes an opportunity, and with every opportunity there is a chance to make improvements for those we are caring for. In England, for example, the current structure of primary care, which now encompasses Primary Care Networks (PCNs), has the potential to drive such developments in care in a population that is living longer but with multiple co-morbidities, and in which health inequalities persist.

PCNs were established in July 2019 and are groupings of local general practices that provide a mechanism for sharing staff and collaborating while maintaining the independence of individual practices. They typically cover a population of around 30 000 to 50 000 people. The COVID-19 pandemic has seen many excellent examples where PCNs have been able to demonstrate the advantages of working in this way, facilitating initiates such as “Hot Hub” working and vaccination delivery in a more efficient way than the previous “siloed working” ethos.

In supporting the objectives of the NHS Long Term Plan, Clinical Commissioning Groups are set to be disestablished in 2022 and PCNs, as they mature, will help to integrate primary care with secondary and community services and the emerging integrated care systems. This is a positive step for people with diabetes, who need to be able to move seamlessly between levels of service provision in response to their changing medical and emotional needs as they travel on their healthcare journey.

This opportunity to develop systems and strategies to better manage long-term conditions has become even more significant now, as we consider how we can reset routine diabetes care as we emerge from the pandemic against a backdrop of capacity and workforce issues across all levels of healthcare provision. Never has it been more important that all healthcare professionals work cohesively to ensure care delivery that facilitates the best outcomes for people with diabetes, whilst also ensuring that healthcare professionals themselves feel confident and supported in their roles.

Delivering best practice across PCNs

A new guide, Best Practice in the Delivery of Diabetes Care in the Primary Care Network, has been produced by a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals as a gold-standard guide for PCNs to benchmark their diabetes services against, and from which they can take any aspects of guidance, recommendations and best practice examples that they feel they would want to implement.

There is recognition that there is significant variation amongst PCNs regarding diabetes service delivery, as PCNs are developing at a different pace across England. Some PCNs are already delivering gold-standard diabetes care whilst others are finding challenges in establishing a basic level of service. The PCN document serves to guide and signpost rather than being prescriptive, and it shines a spotlight on examples where success has been achieved through imaginative use of local services and expertise.

The PCN guide is available here. In addition, we have prepared an accompanying quick guide for the journal, available here.

The CoDES experience

The CoDES (Community Diabetes Education and Support) pilot project is one of many examples of success to choose from. Within Central Manchester, we have looked to many aspects of the care delivery system advocated within the PCN document. The pilot began in 2018, ahead of the formulation of PCNs, but was a service established to work within a neighbourhood of practices (six in total) to deliver best-practice care in an area with a high spend on diabetes and yet relatively poor outcomes, most especially in terms of cardiovascular disease.

A team of two primary care diabetes specialist nurses, under the governance of the secondary care provider and Clinical Commissioning Group, worked in a bespoke way with practices to establish what their needs were. This acknowledged the fact that practices, or indeed PCNs, have the best understanding of their capacity, demographics and, ultimately, the needs of their cohort of persons with diabetes. CoDES offered bespoke support appropriate to each practice’s request, ranging from face-to-face reviews and healthcare professional education, through to email and multidisciplinary team support as required.

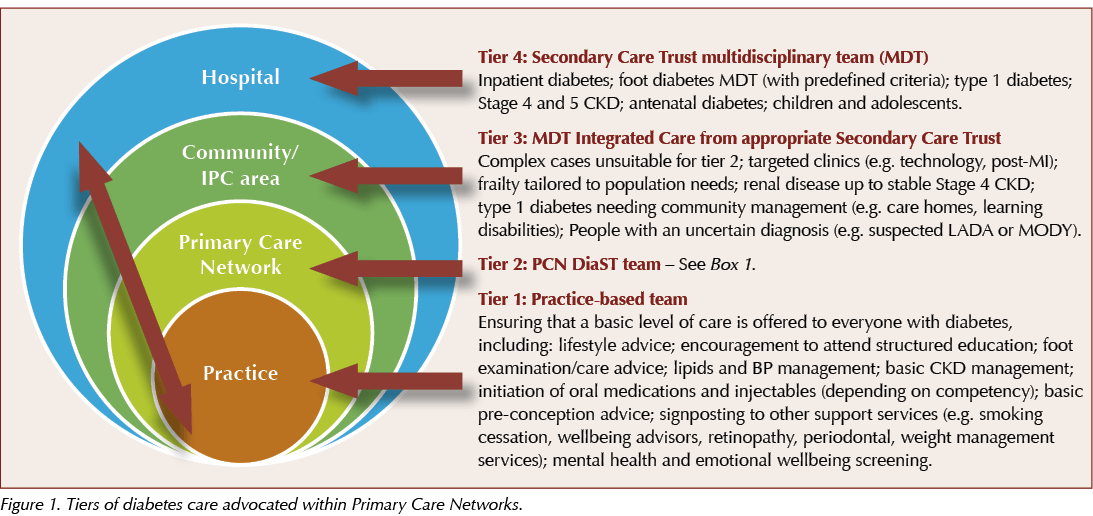

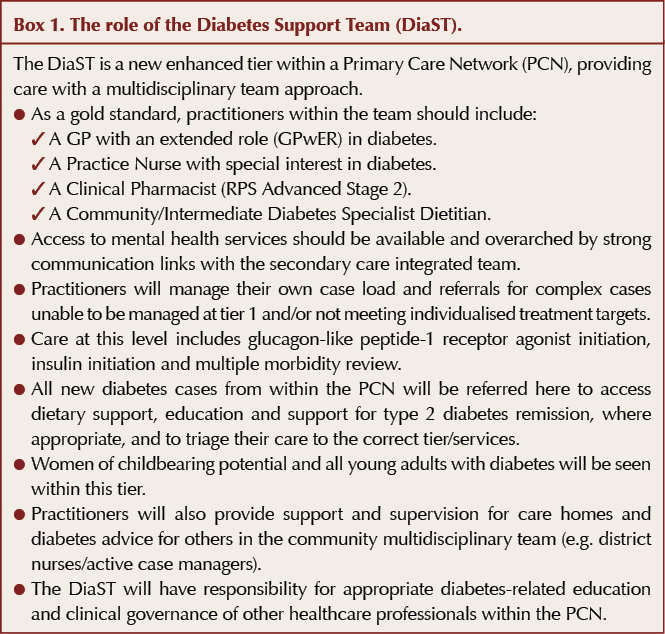

CoDES functioned across different tiers of diabetes care as defined within the guide (see Figure 1). At times it acted as a member of the Diabetes Support Team (Box 1) and at others as part of an Integrated Community Team. The former role was more prominent in the earlier term of the pilot; however, as mentoring, role-modelling and formal education were rolled out, practices evolved their own Diabetes Support Team formations and CoDES began to focus on the tier 3 service, providing care to those with, for example, cardiorenal complications and pre-conception care needs.

Concluding remarks

Primary care is under enormous pressure, and this guide is certainly not intended to add to that burden; rather it is there to help alleviate some of the pressures by providing a template and guidance, including examples of best practice, which would enable PCNs to get off the starting line and develop their services.

We hope this document will give PCNs some food for thought and act as a guide when the services for people with diabetes are being reviewed to provide best possible care for the person with diabetes. In addition it may serve as a useful model for the management of other long-term conditions.

We also hope it will provide an opportunity for a more collaborative approach between primary, community and secondary care, and put an end to siloed working and barriers to care. Doing so will ultimately benefit both service users and providers.

Risk ratios of 1.25 for autism spectrum disorder and 1.30 for ADHD observed in offspring of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy.

18 Jun 2025