The GP surgery involved in this case study, East Leicester Medical Practice, is based in inner-city Leicester and has a higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes than the national average, with just over 1000 people with diabetes on its list of 12,000 patients (prevalence, 8.3%). The practice offers enhanced care as per a local model. Like many general practices, the struggle to recruit GPs and practice nurses in order to deliver sufficient care and proactive review to this group of patients is a real one.

Diabetes specialist nurses have been appointed to care for some of the most complex patients, but the huge workload created by over 1000 people with diabetes has meant the practice has been looking to upskill other team members, such as practice pharmacists.

The role of the pharmacist

Pharmacists are essential in delivering the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019) within both primary and secondary care settings. Clinical pharmacists work alongside GPs, nurses and other healthcare professionals, using their expertise in medicines to improve care for people with a variety of health conditions. The scope of these roles can vary greatly depending on the need of the specific practice, patient demographics and the individual pharmacist’s skill set (Bajorek et al, 2015).

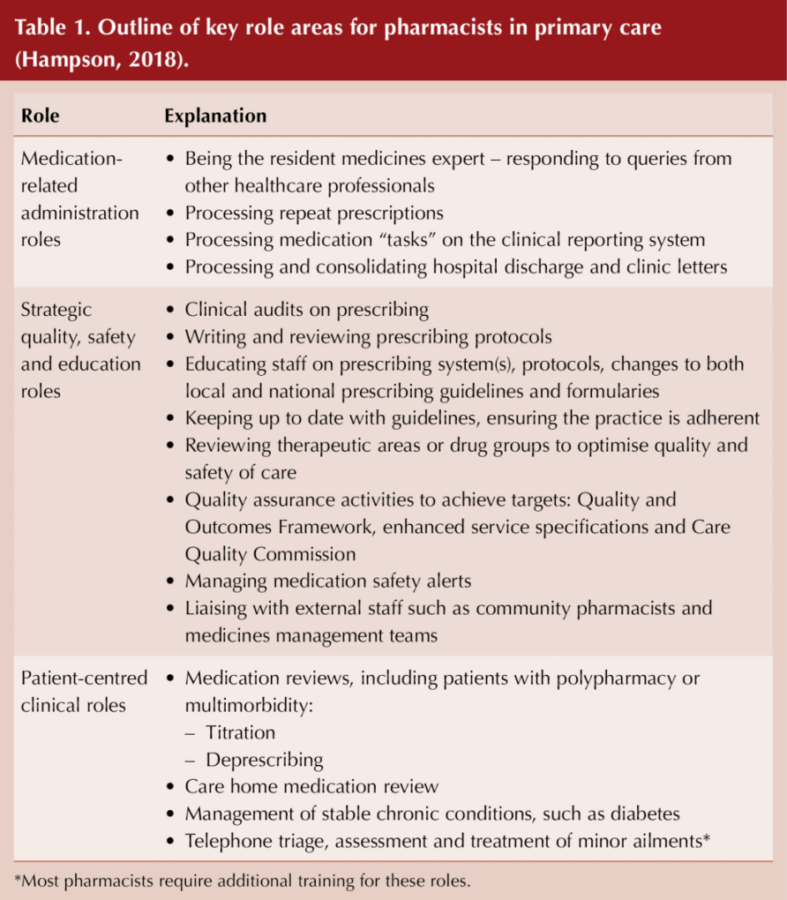

Hampson (2018) outlined three key role areas for clinical pharmacists in primary care, which are also central to diabetes care:

1. Medication-related administration.

2. Strategic quality, safety and education.

3. Patient-centred clinical roles.

These are discussed further in Table 1.

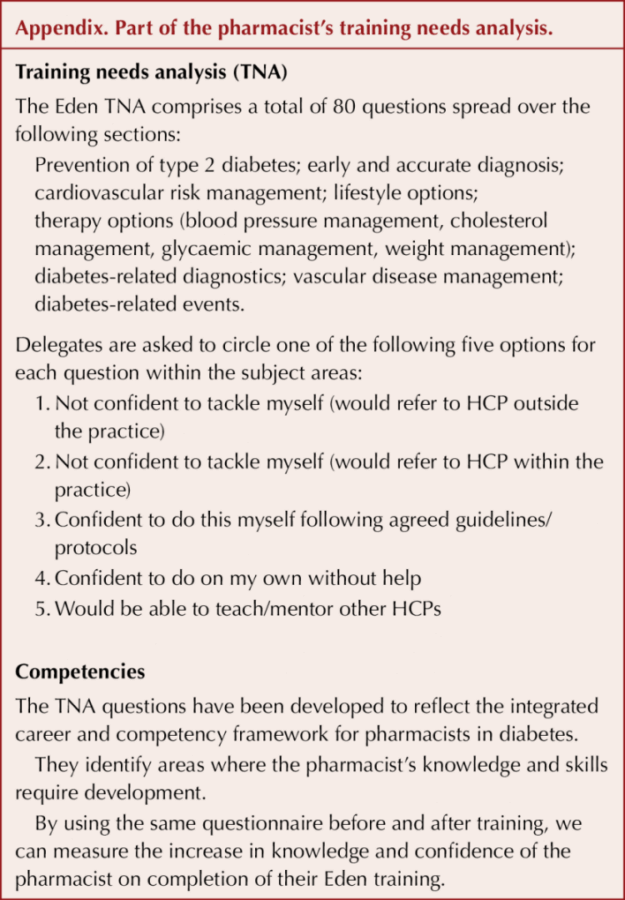

The evolution of such roles has meant the need for rapid upskilling of pharmacists in areas not traditionally included in their training, such as consultation skills and patient assessment (Butterworth et al, 2017). The training group EDEN (Effective Diabetes Education Now), part of Leicester Diabetes Centre, has previously designed bespoke diabetes education to cater for this group of healthcare professionals. The group was approached by a lead GP in early 2018 to design a programme for a new practice-based clinical pharmacist wanting to specialise in diabetes care.

The Integrated Career and Competency Framework for Pharmacists in Diabetes outlines the knowledge required of pharmacists to holistically care for people with diabetes, from their first few years of qualifying all the way to mastery (UK Clinical Pharmacy Association [UKCPA], 2018). The personal objectives of the bespoke training developed by EDEN were based on the training needs analysis of the pharmacist, and can thus be tailored to suit both individual and group needs linked to the framework*:

- EDEN’s structured training days were attended to provide clinical understanding of diabetes progression and management. The training covered topics such as:

– Hypertension management.

– Lipid management.

– Obesity and lifestyle management.

- As well as evidence-based, competency-driven training, EDEN study days provided an opportunity to network with other healthcare professionals, which facilitated sharing of a diverse range of skills and experiences in a protected environment.

- EDEN provided bespoke in-surgery mentoring, supporting the consolidation and real-world application of the theoretical knowledge. This support helped the pharmacist with consultation skills, seeing beyond medicines management for individualised care.

- The practice initiated weekly multidisciplinary team meetings to discuss complex patients and share good practice. This was an integral process to further develop skills and knowledge, highlighting patient-centred care planning.

While there are no specific diabetes competencies for pharmacists working in primary care, the UKCPA competencies do pay special attention to this group of clinicians. Pharmacists must be clear about what competencies are required to deliver diabetes care in a patient-facing role and to work towards demonstrating these competencies in their clinical practice (UKCPA, 2018).

*Part of the training needs analysis can be seen in the Appendix to this article.

Pharmacist-led patient identification and risk stratification

In the surgery, patients were being routinely booked into diabetes clinics regardless of need. The pharmacist led a patient analysis programme to create a risk stratification system. Patients were banded according to HbA1c, blood pressure and lipid levels, and those in the highest bands were seen first. The risk stratification search was run on a monthly basis to identify trends and monitor changes in target areas.

The pharmacist’s treatment perspective

The remit of the clinical pharmacist was to be at least fully equipped to meet the nine care processes for diabetes recommended by NICE. As well as helping people to meet their HbA1c, blood pressure and lipid targets, this also meant ensuring that retinal screening, foot checks, urinary albumin–creatinine ratio testing, weight check and smoking status were recorded and discussed with the patient. However, the training was designed to cover much more than these fundamentals.

Pharmacists are already experts in medicine and quickly adapt to dealing with blood pressure and lipid management, and even the complexities of choosing medications after metformin, de-prescribing, titrating and issues that may arise from polypharmacy in people living with diabetes. As training progressed, however, guidance around practical elements that the pharmacist had not previously been exposed to became more important. This included how to examine injection sites, what to advise to help reduce lipohypertrophy and why these are important aspects of the consultation in those using injectables. Other practical elements, were how to demonstrate devices for administering GLP-1 receptor agonists and insulin – in fact, the list was almost endless!

The pharmacist took a holistic approach to patient care and empowered his patients to make meaningful changes to their lifestyle. Decisions about treatments were made in collaboration, with each individual playing the role of an equal partner in this interaction. Patient education also played a vital role.

Results

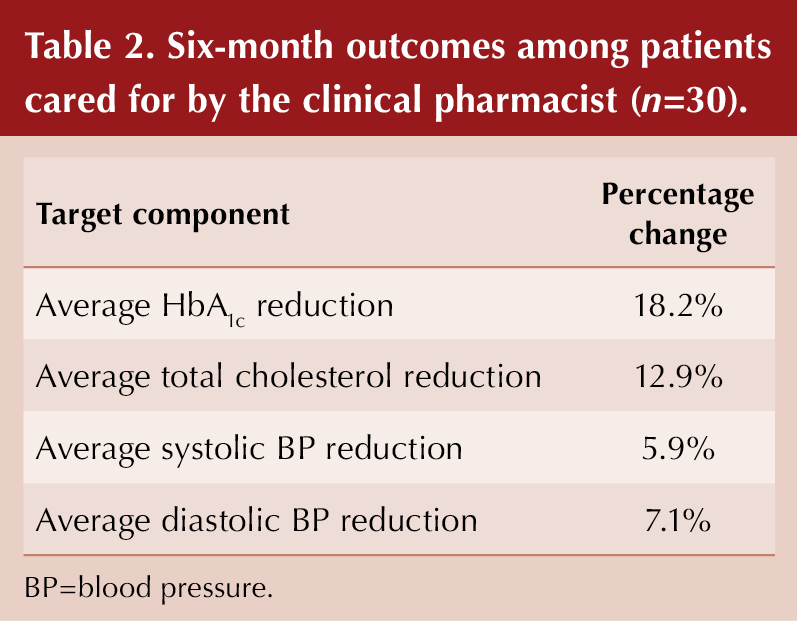

Patient outcomes

Over 6 months, the practice pharmacist conducted approximately 100 consultations and reviews of people with diabetes. An audit was carried out in 30 randomly selected patients who were cared for by the pharmacist over a 6-month period. The changes in target outcome levels are shown in Table 2.

Patient feedback

Anonymised patient feedback was obtained from 25 of the 30 selected participants to build a more comprehensive picture of the impact of the pharmacist’s intervention. The following questions were asked:

- Was the pharmacist polite?

- Did he make you feel at ease?

- Did you feel listened to?

- Did he assess your medical condition?

- Did he explain your condition and treatment?

- Did you feel involved in treatment decisions?

- Did he help you to understand your diabetes?

- Did you set diabetes targets together?

Overall, 97% of responses were “very good” on a five-point scale, and 3% were “good”. In addition, 100% of respondents felt that the consultation helped with their understanding of diabetes and diabetes control; 100% said they were confident in the pharmacist’s ability; and 100% said they would be happy to see him again.

Qualitative feedback was provided by 12 of the 25 participants through questionnaires that had been left at reception in the practice, and which were completed anonymously and without pressure. The feedback shows that the intervention was positively received. Key themes identified through an inductive thematic analysis of the data were:

- Good communication skills.

- Good listening skills.

- Good provision of holistic advice.

One participant said:

Another said:

Professional knowledge and skills

The training needs analysis, which records knowledge and confidence, was repeated after 6 months to identify professional growth. The post-intervention scores demonstrated an improvement in knowledge and confidence of 16% overall, with a 40% improvement in 14 questions (out of 80) and a 60% improvement in one question regarding managing above-target cholesterol. These improvements will undoubtedly enable better quality care provision.

Generalisability

Quantitative and qualitative analysis has demonstrated the success of this programme. However, it would be impossible to attribute all the improvements to the introduction of the clinical pharmacist role. The surgery also benefits from a lead GP who has a specialist interest in diabetes, as well as practice-based diabetes specialist nurses.

It is important to note that there are a number of specific factors that have contributed to the success of this project and need to be noted if other practices are to emulate the success described. Firstly, there are factors related to the individual healthcare professional. The pharmacist was already actively involved in chronic disease management, with an emphasis on cardiovascular risk (lipids, blood pressure, etc.). Although he underwent further training in diabetes, he already had a good foundation of relevant experience for some of the key risk factors for people with diabetes.

Secondly, the pharmacist role concerned is full-time and practice-based; therefore, the pharmacist is committed and involved in the overall performance of the practice in delivering services to its list. Finally, there are factors related to the GP practice. The practice has a team of healthcare professionals who look after people with diabetes; they offer each other regular formal and informal mutual support. The practice also has a good organisational infrastructure and quality assurance and audit mechanisms.

The programme required significant external support from the EDEN training programme to upskill the pharmacist. The requirements for other clinical pharmacists would vary depending on their individual training needs analysis. In this situation, the investment has proved to be worthwhile with this clinical pharmacist.

These various factors cannot be underestimated in contributing to the success of this initiative. However, each practice is unique and others will need to see how they can address the issues of good organisational structure, teamwork and commitment, and upskilling in their own environment and circumstances.

Conclusions

The results of this intervention have been very encouraging and have highlighted how worthwhile this process has been. EDEN support has enhanced the pharmacist’s core consultation skills, enabling him to care for people living with diabetes more holistically. This included adding more practical elements to his skills in medication management. The advantages of mentoring during a clinic, with the patient, pharmacist and EDEN educator present, helps consolidate classroom learning, applying it to “real life”. These sessions have proved to be invaluable, embedding the foundations of good clinical practice. One example outcome is that the pharmacist now always checks injection sites – simple but essential learning. Another welcome consequence has been the reduced need for multiple appointments across the multidisciplinary team.

For people with diabetes, the benefits are already evident. With national shortages of practice nurses, diabetes specialist nurses and GPs, utilising clinical pharmacists to care for people with this condition is an option for GP practices to consider.

This example could be extended as a successful model and interest is growing rapidly, with further requests from practices for similar education and mentoring. The EDEN team has also given training at Pharmacists Federation team meetings, giving an invaluable blend of presentations, opportunities to discuss difficult cases, and question-and-answer discussions.

Risk ratios of 1.25 for autism spectrum disorder and 1.30 for ADHD observed in offspring of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy.

18 Jun 2025