Publisher’s note: This document is associated with a broadcast series funded by Novo Nordisk. Novo Nordisk has had no editorial input into, or control over, the content. PCDS is responsible for all of the content.

Responses by: David Millar-Jones [Chair], GP with a Special Interest in Diabetes, Cwmbran; Su Down, Diabetes Nurse Consultant, Somerset; Kevin Fernanado, GP Partner, North Berwick; and Patrick Holmes, GP, Darlington

COVID-19

Has the pandemic led to worsening glycaemic control and diabetes management? How has your practice changed?

- Many people have had a deterioration in metabolic control, possibly because shielding and lockdown have denied them opportunities for physical activity as well as access to healthcare.

- Many have also been overwhelmed by all the negative headlines and have suffered a huge impact on their mental health.

- Patients can now be divided into two camps: those who are willing and able to aggressively target their diabetes control, and those who just need help to reactivate life as it was before the pandemic, engage with their healthcare and live with less fear.

- Sometimes just a conversation, some support and signposting to services is enough to help.

- When prescribing glucose-lowering medications, members of the panel are now more inclined to prescribe GLP-1 RAs, to help people lose weight and thus get more mobile.

Are there any medications that we need to be cautious about within the context of COVID-19?

ACE inhibitors and ARBs

- Despite early concerns that ACE inhibitors and ARBs might worsen COVID-19 outcomes, they are now deemed safe, and we should carry on using them (European Society of Cardiology, 2020).

- We still need to be cautious with patients who are dehydrated or hypovolaemic, and sick-day rules still apply.

SGLT2 inhibitors

- There are fears that COVID-19 infection can further increase the risk of DKA associated with SGLT2 inhibitors. However, we should prescribe SGLT2 inhibitors (in people with type 2 diabetes) the same way as we were before the pandemic.

- This must include educating the individual about sick day guidance when initiating the therapy, and recommending that they temporarily “pause” the drug if they become ill and are at risk of dehydration – but they must restart it when they get better.

- A consensus statement from Portsmouth Hospital recommends that anyone with type 1 diabetes who has been prescribed an SGLT2 inhibitor by a specialist should stop it while the coronavirus R0 is high. This also applies to people without diabetes who have been prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors to treat heart failure.

- If you have a patient who progressed to insulin within 3 years of type 2 diabetes diagnosis, consider that they might in fact have type 1 diabetes, and so should avoid starting on an SGLT2 inhibitor.

DPP-4 inhibitors: possible benefits?

- There has been some interesting research showing a possible protective effect against COVID-19, but the panel did not recommend altering prescribing practice because of this.

Is it safe to initiate therapies, including injectables, virtually?

- Yes. All of the manufacturers of these therapies have training video clips available for patients (and HCPs) to view prior to an injectable start. There are also very useful clips online to support injection technique, glucose monitoring, etc.

- A benefit of remote video consultations is that they allow HCPs to watch patients administer their therapies and check their injection technique. This should be done regularly, perhaps annually, for all patients.

What advice regarding sick-day rules should we be giving to patients?

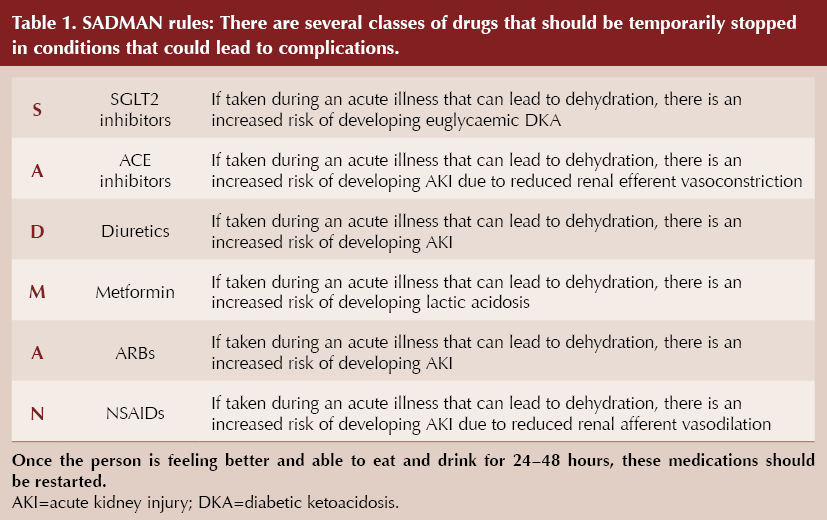

- SADMAN medications (Table 1) should be paused in cases of dehydrating illness, in order to prevent acute kidney injury, lactic acidosis and so on; if someone is not at risk of dehydration, they do not need to stop.

Should general practice be prescribing more blood glucose and ketone monitoring strips?

- Ketone strips (preferably blood, not urine) should be prescribed for higher-risk groups, such as those with type 1 diabetes and those on corticosteroid therapy (see this at-a-glance factsheet for more information). At the very least, there should be access to ketone monitoring during surgery consultations for anyone who is ill and on an SGLT2i, in order to exclude euglycaemic DKA.

- The case for blood glucose monitoring is more nuanced. Someone who starts monitoring glucose more than they were previously may uncover problems, but they may also observe high glucose levels that were already present (particularly in those who already have quite high HbA1c); these may not be a sign of an acute problem but will need guidance/action.

- The key question is whether the person feels unwell in addition to having high glucose, in which case urgent action needs to be taken.

What advice do you have regarding women of childbearing age and COVID-19?

- We need to be offering the usual advice about pre-conception care: avoid pregnancy if HbA1c is >86 mmol/mol (10.0%); take prescription-strength folic acid 5 mg/day for at least 3 months prior to conception and during the first trimester; refer for pre-conception advice to specialist care if possible.

- Consider the medications for glucose, lipid and blood pressure control in those of childbearing age. A full discussion regarding the risks of an unplanned pregnancy whilst taking these therapies (newer glucose-lowering therapies, lipid-lowering drugs and antihypertensives) must take place and be referenced in the patient record. Contraceptive status should also be recorded at the time of prescription of these diabetes therapies.

Guidelines

Which type 2 diabetes guideline does the panel recommend?

- Insofar as all guidelines seem slightly less applicable during the pandemic, the panel’s choice was the ADA/EASD consensus statement (Buse et al, 2019), as this is kept up to date, is easy to follow and most encourages holistic, person-centred care, involving everything from diet/lifestyle through to the cutting-edge drugs.

- The one problem with the consensus is that some of the drugs are not licensed for the recommended uses in the UK (the consensus recommends using drugs with cardiovascular or renal benefits in relevant patients irrespective of HbA1c). Therefore, the SIGN (2017) guideline was also recommended.

What should our priority be when managing people with diabetes? What else should we be targeting apart from HbA1c?

- The current NICE (2015) guideline is very glucose-centric, but this is fast becoming an outlier as other global guidelines focus on treating diabetes comorbidities, and NICE is in the process of updating it.

- Above all, treat the patient in front of you:

– For younger people, weight and HbA1c may be the priority – they stand to have diabetes for a long time, and early prevention of CVD and microvascular complications are most important.

– Older people with frailty: the focus is symptom control and quality of life.

– People with specific needs (e.g. kidney disease) may have improved outcomes with specific antidiabetes drugs.

What are some of the pitfalls when following older guidelines like NICE?

- There are some highly effective medicines with strong evidence to support their use in, for example, heart failure and CKD, which are not recommended in the 2015 NICE guidance as first/second-line therapies. We need to be starting these now in the appropriate patients, rather than waiting for NICE to update its guideline.

- It might even be time to step back from guideline-based care, as modern diabetes medicine does not lend itself to algorithmic management.

What about cost?

- It is cost-effectiveness that is the most relevant factor, not cost itself. Consider the downstream costs (both diabetes complications and COVID-related morbidity).

What are the key studies from the recent research that we can use to back up our clinical prescribing decisions?

- CREDENCE (canagliflozin; Perkovic et al, 2019), DAPA-HF (dapagliflozin; McMurray et al, 2019), VERTIS-CV (ertugliflozin; Cannon et al, 2020) and EMPEROR-Reduced (empagliflozin; Packer et al, 2020) are all recent trials that reiterate the favourable risk:benefit ratio for the SGLT2 inhibitor class.

Would the panel consider starting with more than one therapy at initiation, as per some guidelines?

- As part of individualised care, this is an option for some. For someone who has begun with pre-diabetes and has implemented diet and lifestyle changes but still progressed to type 2 diabetes, treatment could be started more aggressively.

- In contrast, people who have not yet tried lifestyle change should be given the opportunity and support to do so first.

- Someone who is quite young and has a strong family history of CVD, for example, should probably start on a drug with proven cardiovascular benefit from day one.

With evidence that GLP-1 RAs have CVD benefits, is it right to follow NICE recommendations to withdraw them if the individual does not have improved HbA1c or weight loss?

- The guideline is out of date as it was published before this evidence was available. Again, we must treat the individual, and in this case the individual would not be served by withdrawing the agent.

- It may also be appropriate to switch to a different drug in the same class to achieve additional benefits, as they may have different effects.

Are there any guidelines for discontinuing medications, either in people who have started to achieve HbA1c targets or those for whom certain therapies are not working?

- There will probably be local guidelines recommending to stop, for example, GLP-1 RAs if they do not lower HbA1c or weight. However, before doing so, HCPs must always consider whether the individual is in fact taking the drug as prescribed.

- Deprescribing is very important in frail older patients – this centres around protecting them from the risk of hypoglycaemia.

Glucose-lowering drugs

How quickly should we be starting and escalating therapy in people with high HbA1c at and after diagnosis?

- There is some evidence that metformin has its highest rate of side effects in people with high HbA1c at initiation.

- It is essential to make these decisions with the patient so that they do not lose faith in the drug immediately.

- For someone with very high HbA1c at initiation, consider starting with a sulfonylurea in the short term whilst uptitrating metformin; the sulfonylurea could then be withdrawn once metformin is at the required dose and glycaemic control is achieved.

- Experience from antenatal clinics is that, if motivated, people can titrate their metformin up from 0 to 2 g in a week, but it comes down to the individual having the understanding and desire to do this quickly.

Would the panel ever initiate insulin at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes with no other comorbidities?

- Yes, in those with severe osmotic symptoms, perhaps those with steroid-induced hyperglycaemia, in order to bring glycaemia down quickly to avoid beta-cell glucotoxicity. A sulfonylurea could also be considered here. Initiating insulin does not necessarily commit the user to insulin for the long term.

- The thin person with type 2 diabetes may also need insulin at diagnosis – whilst also making sure to confirm the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

Can you give advice about how to adjust insulin dose – basal and bolus?

This is a vast topic to cover in a short reply, and dose adjustments should only be made by those HCPs who are competent to do so, but here are some quick tips:

- When making dose adjustment, wait for a pattern to emerge from regular glucose monitoring and look to elicit the cause of that pattern. Dose adjustment may not be required but rather diet/lifestyle modification or review of injection technique.

- Always prioritise prevention of hypoglycaemia before high glucose levels.

- If dose reduction is needed to prevent hypoglycaemia, reduce the dose by 20% at least.

- If a dose increase is needed, increase the dose by 5–10%.

Is there still room for sulfonylureas in diabetes care?

- These remain very effective glucose-lowering agents, they are cheap and they do not appear to increase cardiovascular risk compared with DPP-4 inhibitors (Rosenstock et al, 2019).

- However, the panel typically use them as third- or fourth-line agents.

- Someone presenting with high HbA1c, perhaps with osmotic symptoms, could certainly benefit (although perhaps the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes should also be questioned here), as could those whose diabetes is progressing and will likely need insulin but are reluctant to start it.

Are there grounds for switching to a different GLP-1 RA if the patient’s current one is not effective?

- There are many differences between the drugs in terms of half-life, dosing, etc., that may lead to differing effects. The evidence to support GLP-1 RA use is so compelling that trying a different one is recommended. There may also be cost benefits to switching: for example, from the 1.8 mg dose of liraglutide to either dulaglutide or semaglutide.

- Insulin/GLP-1 RA combinations are also available. These can be started at much lower GLP-1 RA doses and thus may be better tolerated.

- Currently, the panel views weekly semaglutide as the gold-standard GLP-1 RA, for those who can tolerate it, although new data are constantly being published.

If switching from one GLP-1 RA to another, would you still start at the lower dose and build up, or go straight to the standard dose?

- This depends on the potency of the GLP-1 RA. If the aim of the switch is to improve glucose/weight outcomes and there is no retinopathy, then a switch to the most potent drug, semaglutide, would be the preferred choice. The panel recommends the following, although this advice is not specified in semaglutide’s Summary of Product Characteristics:

– If a person is on the treatment dose of a GLP-1 RA and you wish to start semaglutide, then switching to an initial 0.5 mg dose is reasonable to consider; however, when switching from an initial/low dose of GLP-1 RA (lixisenatide 10 µg, liraglutide 0.6 mg or dulaglutide 0.75 mg), the initial 0.25 mg dose of semaglutide would be advised.

What does the panel think about oral GLP-1 RAs?

- Oral semaglutide is a useful addition but will not be a panacea for type 2 diabetes. Although not an injectable, its administration is not necessarily easy: it needs to be taken on waking, on a completely empty stomach, with no more than 120 mL of water, and then the user has to wait at least 30 minutes before consuming food, drink or other medications; otherwise, it will not be absorbed and effective.

– This fact needs to be reinforced: it cannot be taken with a morning cup of tea! - The 30-minute gap is also important because oral semaglutide can interfere with other drugs. It also cannot go in a blister pack, which may be of concern in older patients.

- On the other hand, it has some benefits, including the flexibility to use it down to an eGFR of 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, as with the injectible.

If oral semaglutide needs to be given on an empty stomach, what would be your advice for those patients who may be on other medications such as bisphosphonates?

- An injectable GLP-1 RA would be advised for this individual as administration will be very challenging for both oral semaglutide and the oral bisphosphonate, as both should be taken in the morning on an empty stomach and separate from other medications or food.

- While monthly oral and annual intravenous formulations of bisphosphonates are available, a weekly GLP-1 RA injection would probably be easiest.

When starting a therapy in an individual with CVD, would the panel start metformin and either a GLP-1 RA or an SGLT2 inhibitor at the same time?

- Again, on an individual basis, yes. For example, in someone who has had a myocardial infarction which unmasked the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

- Note that the three drugs recommended for those with type 2 diabetes and CVD by the ADA/EASD – metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs – also have the greatest side-effect profiles. It is therefore essential to make this decision in discussion with the patient.

My patient aged 87 years has a very high HbA1c of 116 mmol/mol on metformin (500 mg twice daily – she cannot tolerate more) and sitagliptin. Her BMI is 38 kg/m2. What is the panel’s next choice of drug?

- In this scenario, consider insulin, particularly if there were significant osmotic symptoms or there was an element of frailty.

- A GLP-1 RA could be considered if type 1 diabetes was excluded, there was no frailty and perhaps there was evidence of atherosclerotic CVD, although weight loss in this cohort of patients is typically not a goal of treatment, due to the risk of sarcopenia.

HbA1c in older people can be artificially higher. How should treatment be approached?

- In clinical practice we are talking about very small differences when other factors are corrected for: around 0.1%, which is not clinically relevant. More helpful is the trend in HbA1c.

- Establish frailty status and then aim for an HbA1c appropriate for that status:

– Fit and well: target 58 mmol/mol (7.5%).

– Moderate to severely frail: target 64 mmol/mol (8.0%).

– Severely frail: target 69 mmol/mol (8.5%). - These levels allow for that rise in HbA1c with age (i.e. even fit, well older people should aim for an HbA1c of no less than 58 mmol/mol). This would equate to an HbA1c of 53 mmol/mol in a person 3–4 decades younger.

Concluding remarks

- The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a deterioration in metabolic control in many people, possibly because shielding and lockdown have denied them opportunities for physical activity as well as access to healthcare.

- We have a number of guidelines, but no single one is perfect for each patient and we need to focus on treating the individual person.

- Remember to intensify therapy if needed, but also don’t forget to de-prescribe if appropriate.

- Some newer therapies offer more than just glucose-centric management (cardiovascular and renal benefits, weight loss), and we need to consider safety and long-term cost-effectiveness.

Risk ratios of 1.25 for autism spectrum disorder and 1.30 for ADHD observed in offspring of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy.

18 Jun 2025