Management of people with COVID-19 and diabetes

David Millar-Jones, GP with Special Interest in Diabetes, Cwmbran

- People with diabetes are more at risk of mortality and significant illness with COVID-19; age and poor glycaemic control increase the risk further.

- South Asian and African–Caribbean ethnicity increases risk of serious COVID-19 and poorer outcomes, including in those working as healthcare professionals.

- Men are at greater risk of serious outcomes, despite men and women having the same frequency of COVID-19 infection.

- The mechanisms by which many risk factors influence the seriousness and mortality rates remain unclear.

- COVID-19 is not restricted to involvement with the respiratory system. Ear, nose and throat, neurological and cardiological conditions also occur.

- Data from Wuhan, China, showed an overall case fatality rate of 2.3%, but of <1% in those without chronic diseases. This rose to 6% in those with hypertension, 7.3% in those with diabetes and 10.5% in those with cardiovascular disease, which is comparable to the case fatality rate of 10.2% in those aged >70 years (The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team, 2020). This means that we should continue to be proactive in measures to improve glycaemic control, reduce cardiovascular risk and encourage weight loss.

- ACE inhibitors and ARBs result in upregulation of ACE receptors, which are involved in entry of the COVID-19 virus into the cells. However, several organisations have reviewed the evidence and concl uded that we should not make any change to the way we use these drugs.

- People with diabetes should observe the same precautions to prevent themselves contracting COVID-19 as the general population.

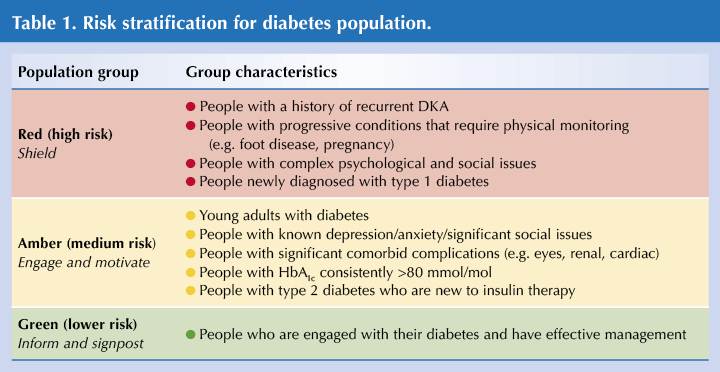

- It can be useful to categorise people into risk groups and by the amount of sick-day support and guidance they require (see Table 1).

- In discussion with people with diabetes, we need to remember the high levels of distress and depression that they may be experiencing, and help them to manage these as well as their diabetes.

- For those with type 1 diabetes taking SGLT2 inhibitors as additional therapy, this therapy should be stopped due to the high risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). People with type 2 diabetes on insulin with previous DKA should also stop SGLT2 inhibitors. Other people with type 2 diabetes can continue to use an SGLT2 inhibitor, but should stop temporarily if they develop COVID-19 or other illnesses (MHRA, 2020).

- Clinicians should be aware of “long COVID”, the longer-term clinical consequences post-COVID infection. A cough can normally be present for up to 4 weeks, but evidence is emerging of longer-term respiratory, cardiac, gut, neurological and mental health symptoms that may be present for 8 weeks or longer.

- COVID-19 appears to have four phases that may be influenced by diabetic control and therapies:

- Viral invasion and replication.

– In vitro studies have shown that the binding of the virus to a cell increases with statin therapy, ACEi and ARB therapy, and hyperglycaemia. It is attenuated by insulin and DPP-4 inhibitor therapies. - Immune recognition and replication in the lung.

- Pneumonia, leading to lung damage.

- Respiratory distress/cytokine storm/multiple organ failure.

–Cytokine storm is associated with increased mortality. Steroids have shown some benefit and are currently being used. The anti-inflammatory nature of statins, ARBs and ACEis, and DPP-4 inhibitors may offer some protection.

- The evidence is still emerging and so these studies should not influence current prescribing in general practice.

Resources

- How to undertake a remote diabetes review: bit.ly/3gwiBQU

- How to prioritise primary care diabetes services during and post COVID-19 pandemic: bit.ly/3nc4nIe

Sick day management

Julie Lewis, Nurse Consultant, Primary Care Diabetes, Central Area, North Wales

- For a person with diabetes, intercurrent illness often leads to worsening hyperglycaemia. Usual treatments that a person may be taking for their glycaemic control are often insufficient and need to be increased, changed or, in some cases, temporarily withheld to reduce the risks of acute kidney injury (AKI).

- People with diabetes are more clinically vulnerable to the serious effects of COVID-19. It is important, therefore, that primary care services afford the opportunity for those who need support to optimise their diabetes self-management. Tools for self-monitoring should be provided and a strategy for coping with illness according to their individual treatment plans discussed.

- Plan ahead to support self-management in the event of acute illness episodes. Use resources, such as the SADMAN rules, to reinforce illness management strategies.

- Often the potentially “nephrotoxic” medications (e.g. ACEi/ARBs, diuretics) are discontinued following an admission to hospital with AKI. Consider the presence of comorbidities (such as heart failure) that are likely to worsen if these medications are not restarted once the intercurrent illness episode is over. Assess the risks and benefits in each case, and liaise with local heart failure teams to support treatment optimisation.

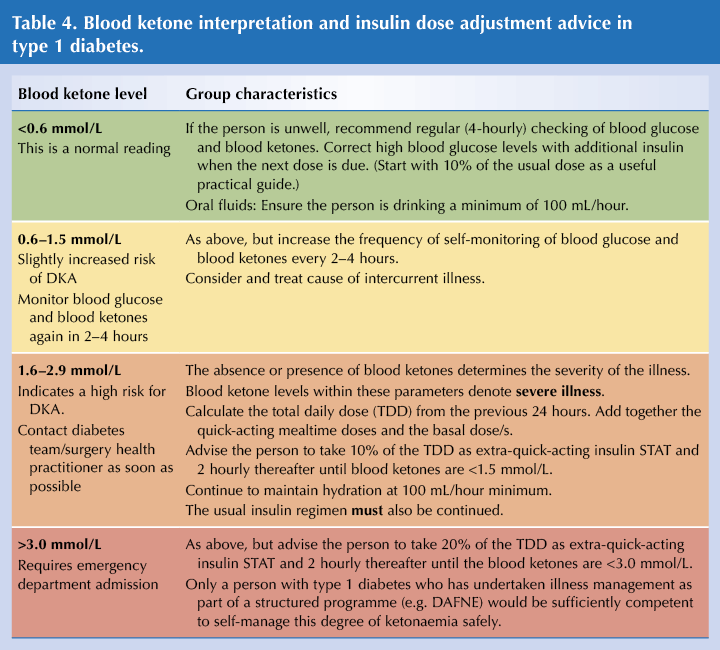

- There are many resources for effective insulin dose adjustment during acute illness episodes (see Resources below). These are useful, but seek advice from a specialist practitioner if you are unfamiliar with putting the guidance into practice, especially in type 1 diabetes.

- In the presence of significant ketonaemia, adopt a low threshold for emergency department admission. Definitely admit if there is vomiting, as dehydration will hasten deterioration.

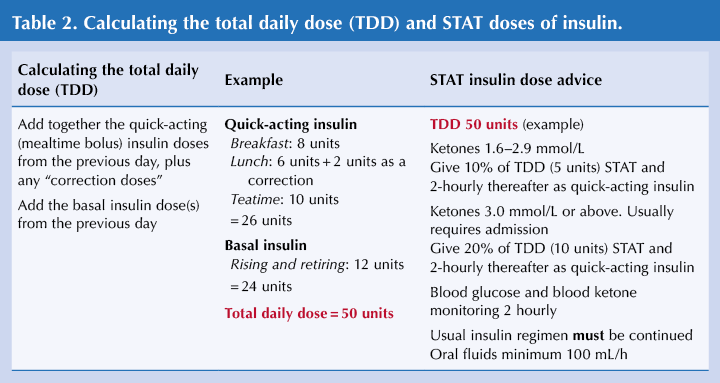

- A practical approach will be to start with the advice in Table 2. Assess the person’s confidence, competence and capability to self-manage these insulin dose adjustments during an acute illness episode. Even if conveying the person to hospital, starting the additional insulin as an immediate STAT dose will be beneficial.

- Remember that insulin dose adjustment during illness management is a core component of recognised structured diabetes education programmes.

Resources

- How to advise on sick day rules: bit.ly/39zBPjB

- Trend Diabetes. What to do when you are unwell patient leaflets: https://trenddiabetes.online/resources

Diabetes shorts: Kidneys

Sarah Davies, GPwSI in Diabetes, Cardiff

- Our role in primary care in patients with diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is threefold: identify and delay progression of DKD, reduce cardiovascular risk and manage hyperglycaemia appropriately.

- Screening for kidney disease requires both eGFR and urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) testing. Urinary ACR is a good early warning sign of DKD but is underused.

- DKD increases cardiovascular risk, so good management of lifestyle factors, and tight (but individualised) blood pressure and lipid targets are important.

- There are exciting developments relating to the SGLT2 inhibitor class of drugs and DKD management, with emerging evidence of renal protective qualities. International guidelines recommend the use of an SGLT inhibitor early in the treatment pathway for people with DKD, and independently of glycaemic control. As new evidence emerges, licences may be extended to the treatment of chronic kidney disease, as we have seen recently with canagliflozin.

Diabetes shorts: Heart failure in the context of diabetes

Richard Chudleigh, Consultant Physician and Diabetologist, Singleton Hospital, Swansea

- Heart failure (HF) – remember the four Fs:

– Often the first presentation of cardiovascular disease in people with type 2 diabetes.

– Frequent – up to two thirds of people with type 2 diabetes in some studies have left ventricular dysfunction within 5 years of diagnosis.

– Forgotten – up to 28% of people with type 2 diabetes may have undiagnosed HF.

– Fatal – high mortality rate if type 2 diabetes and HF.

– Frequent – up to two thirds of people with type 2 diabetes in some studies have left ventricular dysfunction within 5 years of diagnosis.

– Forgotten – up to 28% of people with type 2 diabetes may have undiagnosed HF.

– Fatal – high mortality rate if type 2 diabetes and HF.

- Causes of HF in those with diabetes: the commonest are coronary artery disease and following myocardial infarction; some have diabetic cardiomyopathy.

- There is a bidirectional relationship between HF and type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes results in hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance, which increases the risk of HF; HF increases insulin resistance and increases type 2 diabetes.

- The mortality rate is high – 6% during the first hospitalisation for HF (HHF) and 40% by 2 years.

- Data from the UK Prospective Diabetes Study showed that every 1% (10.9 mmol/mol) increase in HbA1c is associated with a 16% increased risk of HF as well as increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and peripheral artery disease.

- Management: Follow the 2019 update to the ADA/EASD consensus on glycaemic management (as the NICE guidance is out of date). It recommends the preferential use of an SGLT2 inhibitor in those with HF and of a GLP-1 receptor agonist in those with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (Buse et al, 2020).

- A significant reduction in HHF in high-risk people has been demonstrated in studies with empagliflozin, canagliflozin and dapagliflozin.

- Rather than HbA1c reduction, a variety of mechanisms are likely to contribute to the benefits seen with SGLT2 inhibitors, including several mechanisms related to natriuresis.

Risk ratios of 1.25 for autism spectrum disorder and 1.30 for ADHD observed in offspring of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy.

18 Jun 2025