Testosterone plays a crucial role in the development and maintenance of secondary male characteristics, and is essential for a variety of physical, sexual, cognitive and metabolic functions (Dandona and Rosenberg, 2010).

When testosterone levels drop, individuals can suffer a variety of physical and psychological effects, and a subsequent decrease in quality of life (Dean et al, 2015). Despite this, there remains controversy and uncertainty about how to manage this problem in primary care.

Testosterone deficiency (TD) is an increasingly common problem, largely owing to increased life expectancy and an increase in the prevalence of risk factors that include obesity, type 2 diabetes, the metabolic syndrome and a sedentary lifestyle.

To address this situation, the British Society for Sexual Medicine (BSSM) has produced a 20-page evidence-based guideline to help physicians manage the situation (Hackett et al, 2017a). This is both feasible and rewarding in a primary care setting. This article is based on the BSSM guidelines.

TD is a clinical and biochemical syndrome, with relevant signs and symptoms accompanying low serum androgen levels. It is usually associated with older age and comorbidities (Dean et al, 2015; Khera et al, 2016).

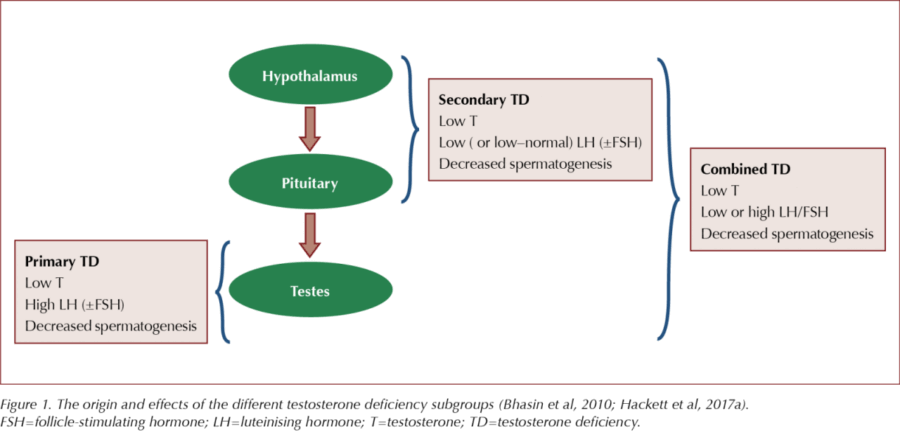

TD results when the testes fail to produce sufficient testosterone for normal body function. This is caused by dysfunction of one or more levels of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis, originating in the testes (primary TD), the hypothalamus/pituitary (secondary TD) or the testes and hypothalamus/pituitary (Figure 1).

TD may also result from: impaired testosterone action (variations in sex hormone-binding globulin [SHBG] can decrease bioavailability; Dean et al, 2015); reduced androgen activity (may follow changes in the androgen receptor; Dean et al, 2015; Liu et al, 2012); and the long-term use of some medications (such as oral glucocorticoids, antipsychotics and opioids; Inder et al, 2010; Lunenfeld et al, 2015; Bagworm et al, 2015).

The term functional TD (also known as late-onset, adult-onset and age-related TD) has been used to describe low testosterone levels and associated symptoms in men older than 50 years. In the absence of intrinsic, structural HPG axis pathology (e.g. microprolactinoma) or specific pathology suppressing the HPG axis (e.g. endogenous Cushing’s syndrome), it is associated with conditions like obesity and the metabolic syndrome (Grossman and Matsumoto, 2017).

Compensated (subclinical) TD is characterised by normal testosterone levels, high luteinising hormone (LH) levels and older age. These patients should receive regular monitoring, as they may later develop overt primary TD (Tajar et al, 2010).

Estimates of TD prevalence vary widely in epidemiological research. In the European Male Aging Study (EMAS), TD prevalence was 2.1% overall. Rates in men increased with age, from 0.1% in their 40s to 0.6% in their 50s, 3.2% in their 60s and 5.1% in their 70s (Wu et al, 2010). The prevalence of primary TD was 2%, secondary TD 11.8% and compensated (subclinical) TD 9.5% (Tajar et al, 2010).

While the prevalence of TD increases with age (Khera et al, 2016), more than 70% of men in EMAS maintained normal testosterone levels into older age, underscoring that TD is not only related to ageing (Tajar et al, 2010).

Many signs and symptoms of TD are multifactorial in origin and, in addition to the normal ageing process, are associated with various lifestyle and psychological factors. As a result, they may also be found in men with normal testosterone levels (Kaufman and Vermeulen, 2005; Dohle et al, 2017).

Sexual symptoms are the most common finding, and most candidates for testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) present with sexual dysfunction and a desire for treatment. The sexual symptoms include erectile dysfunction, loss of early morning erections, low sexual desire, delayed ejaculation and a reduction in the volume of ejaculate. Delayed puberty and infertility may also be an issue (Dean et al, 2015; Khera et al, 2015; Lunenfeld et al, 2015; Dohle et al, 2017; Hackett et al, 2017b).

Physical signs and symptoms include small testes, gynaecomastia, decreased body hair, hot flushes/sweats, disturbed sleep, tiredness/fatigue, a reduction in muscle mass and strength, osteoporosis, height loss and low-trauma fractures (Dean et al, 2015; Khera et al, 2015; Lunenfeld et al, 2015; Dohle et al, 2017; Hackett et al, 2017b).

Psychological signs/symptoms include mood changes, such as sadness, depression, anger and irritability, decreased well-being or poor self-rated health, and reduced cognitive function, including impaired concentration, verbal memory and spatial awareness (Dean et al, 2015; Khera et al, 2015; Lunenfeld et al, 2015; Dohle et al, 2017; Hackett et al, 2017b).

TD is also associated with, and may lead to, metabolic disturbances, including visceral obesity, increased BMI, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (Dean et al, 2015; Khera et al, 2015; Lunenfeld et al, 2015; Dohle et al, 2017; Hackett et al, 2017b). The more signs and symptoms are present, the greater is the likelihood of genuine TD (Zitzmann et al, 2006; Lunenfeld et al, 2015).

TRT has been demonstrated to improve the signs and symptoms of TD and reduce cardiovascular risk. With treatment extending beyond 6 months, there is evidence of benefit in body composition, bone strength and features of the metabolic syndrome. In men with TD, TRT is associated with reductions in BMI and waist circumference, and improvements in glycaemic control and lipid profile. TRT has also been shown to improve sexual desire, erectile function and sexual satisfaction.

Various long-term studies, reviews and meta-analyses support the association between TD and increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (Haring et al, 2010; Araujo et al, 2011; Ruige et al, 2011; Muraleedharan et al, 2013; Yeap et al, 2014; Daka et al, 2015), but there remains a lack of evidence for the pathogenic link, which is probably multifactorial (Lunenfeld et al, 2015; Hackett, 2016).

Recent research has provided compelling evidence for the safety of TRT, with a reduction in mortality in clearly defined TD treated to the therapeutic range.

TRT does not appear to increase the risk of prostate cancer and may be used under close supervision in men cured of the disease. TRT should only be offered to men who have treated, localised, low-risk prostate cancer (Gleason score <8, stages 1–2, preoperative PSA level <10 ng/mL) and no evidence of active disease (based on PSA level, digital rectal examination result and absence of metastatic disease) after a minimum follow-up of 1 year.

Lifestyle modification is an important component of TD management and should be initiated in combination with TRT.

Physicians need to familiarise themselves with the available testosterone formulations to fully inform patients about the expected benefits and side effects, and facilitate a joint decision on treatment choice.

Thresholds for therapy have been clearly defined for symptomatic men: a total testosterone (TT) level greater than 12 nmol/L or a calculated free testosterone (FT) level (using SHBG) greater than 0.225 nmol/L does not require therapy (BSSM, 2010; ISSM, 2015; Hackett et al, 2017b). A TT level <8 nmol/L or a FT level <0.180 nmol/L usually requires TRT. TT levels of 8–12 nmol/L may require a trial of TRT for a minimum duration of 6 months, based on the patient’s symptoms (BSSM, 2010; ISSM, 2015; Hackett et al, 2017b). A FT level <0.225 nmol/L supports the evidence for TRT in the presence of appropriate symptoms (Antonio et al, 2016). TRT should also be considered in men with increased LH levels and TT below normal or in the low quartile range, as this indicates testicular failure (Tajar et al, 2011; Lunenfeld et al, 2015).

Conclusion

TD is an increasingly common problem, with both physical and psychological implications. Importantly, TRT can reduce TD signs and symptoms and improve quality of life in affected patients, with a reduction in mortality. While early diagnosis and optimal management is important, attention to detail in follow-up is essential. A more detailed paper describing the BSSM recommendations on diagnosing, managing and supervising TD will be included in the next issue of the Journal.

Jane Diggle discusses emotional health and diabetes distress, and offers some tips for discussing this in our consultations.

11 Nov 2025