The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in children and young people is increasing significantly. Studies have demonstrated that this group develops higher rates of complications compared to adults with type 2 diabetes and children with type 1 diabetes (Pinhas-Hamiel and Zeitler, 2023). Remission, defined as an HbA1c of <48 mmol/mol measured at least 3 months after ceasing glucose-lowering pharmacotherapy (Riddle et al, 2021), is recognised as an appropriate management aim (Davies et al, 2018).

The prevalence of severe obesity, a significant risk factor for youth-onset type 2 diabetes, has quadrupled worldwide since 1990 (World Health Organization, 2025). One meta-analysis found that 77% of children diagnosed with type 2 diabetes were obese (Cioana et al, 2022). As obesity prevalence increases worldwide, there are more reports of type 2 diabetes in prepubertal children. During puberty, there is an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes owing to a surge in hormones such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which at high levels is associated with insulin resistance (Gungor et al, 2005). Continued weight gain, particularly in the form of adiposity, in children who develop type 2 diabetes around puberty contributes to insulin resistance and a deterioration in glycaemic control. Although insulin resistance is hard to measure, it can be expressed clinically in the form of acanthosis nigricans, early poor growth and comorbidities like hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and polycystic ovary syndrome (White et al, 2024).

Genetics play a large role in the development of type 2 diabetes, which has a stronger link to family history than type 1 diabetes. Prevalence also differs substantially among ethnic groups. Intrauterine exposure to diabetes is an established risk factor, while other contributing factors include poor mental health, short sleep duration, social isolation, a sedentary lifestyle and some eating disorders (Engum, 2006). Prevalence in men and women can vary with age, but women appear to face a greater burden of risk factors (Kautzky-Willer, 2023). Limited access to healthy food and reduced opportunities for physical activity owing to low socioeconomic status contribute to the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in young people.

Prompt intervention is essential for children and adolescents diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. In the UK, paediatric diabetes services primarily follow NICE guidance, which recommends early, individualised intervention combining lifestyle modification, blood glucose monitoring and pharmacological therapy, including metformin at diagnosis where appropriate (NICE, 2023). International guidance from the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD; Shah et al, 2024) broadly aligns with NICE recommendations and may be used as a complementary reference, particularly in relation to structured education and behavioural approaches, but does not replace NICE guidance in UK clinical practice.

While current guidelines focus on achieving and maintaining glycaemic control, there is comparatively less emphasis on structured pathways to diabetes remission, particularly in younger individuals. Early therapy involves lifestyle modification and metformin, with a GLP-1 receptor agonist considered as second-line treatment once early ketosis and symptoms are managed. The case study presented below offers a practical illustration of how remission may be achieved through intensive lifestyle intervention alongside pharmacotherapy, and may help inform future refinement of existing guidance.

To reduce the symptoms of type 2 diabetes and the risk of complications, it is essential to provide the child with type 2 diabetes and their family or carer with a programme of education that includes diet, reducing body weight and increasing physical activity. Hypertension and dyslipidaemia should be monitored from diagnosis, and a smoking cessation programme offered where necessary.

There is no conclusive evidence defining a specific weight‑loss target for young people with type 2 diabetes but, in adults, calorie restriction and associated weight loss have been shown to increase rates of diabetes remission (Jayedi et al, 2023), with greater weight loss linked to higher remission likelihood. For such interventions to be effective in young people, they must be acceptable, feasible, and tailored to support adherence and long‑term sustainability (Stok et al, 2016). A whole-family approach should be used to enable change, with a personalised plan that accounts for social and cultural considerations (Young-Hyman et al, 2016). Psychological support to ensure adherence to therapy should be considered, while NICE (2025) provides guidance on physical activity to manage overweight and obesity in young people.

Case report

Patient information and clinical findings

A 12-year-old prepubertal girl of White ethnicity (pseudonym KR), a weight of 90.0 kg, height of 1.47 m and a BMI of 42.8 kg/m2 presented with left lower abdominal pain, frequent urination, nausea and headache with no episode of emesis. Suspecting a urinary tract infection, an antibiotic regimen was initiated.

Upon further examination, an incidental finding of elevated blood glucose levels (16.4 mmol/L) was noted. Her HbA1c level was 54 mmol/mol, serum ketones 0.1 mmol/L, heart rate 112 bpm, while her blood pressure could not be measured. Her C-reactive protein (CRP) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were elevated at 12 mg/L and 74 U/L, respectively. No lipid profile was obtained upon admission.

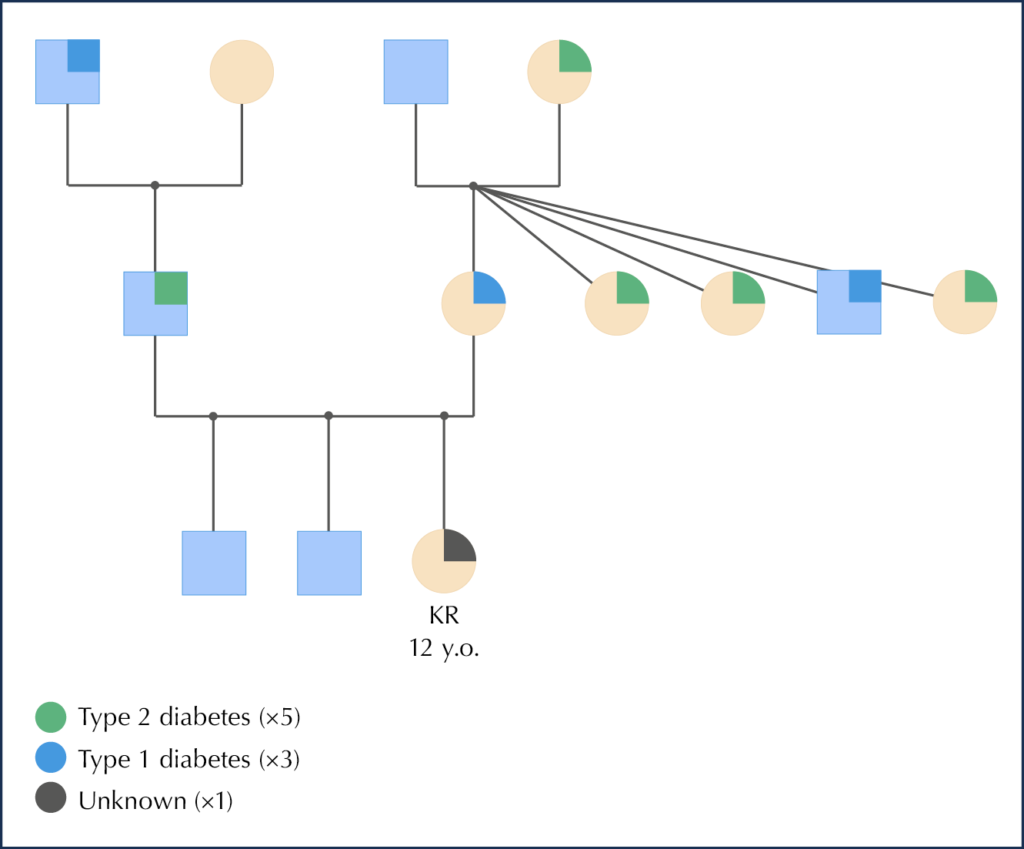

KR’s mother was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at 15 years and her father with type 2 diabetes under the age of 16 years, with a continuous lack of adherence to his prescribed treatment regimen. There was history of metabolic disorder on both the mother and father’s side of the family. Her paternal grandfather was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and had to have his leg amputated due to complications from suboptimal sugar levels. The family structure along with KR diagnosed in members of the family is shown in Figure 1.

The patient is enrolled in full-time education and has positive relationships with a small circle of friends and her mother. The mother is a homemaker and the father is a mechanic. There are two older brothers in the household; one has a selective/picky appetite, while the other follows a vegan diet, which may influence household eating patterns. KR did not have any previous medical history. She had previously sought assistance for weight management at her former local trust, and was subsequently referred to a different hospital in December 2022 due to relocation. A single education session on weight management was provided, which included information on the Eatwell Guide and physical activity, but she gained 11 kg subsequently.

Diagnosis

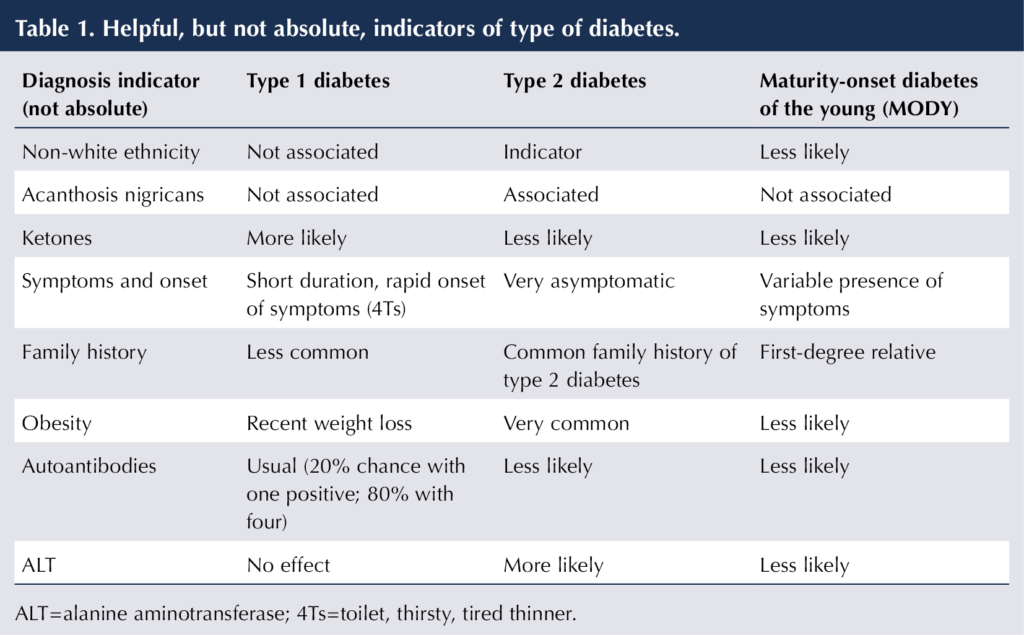

Acute cystitis and type 1 diabetes were considered as differential diagnoses. A diagnosis of the latter was made based on KR’s signs, symptoms and medical history. Blood was collected to conduct an autoantibody test and verify the diagnosis. KR did not have acanthosis nigricans. A persistent elevation in ALT levels suggested metabolic dysfunction (Wang et al, 2024). In line with UK paediatric practice, she was treated according to NICE guidelines for newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes.

Treatment

1. Initiation of insulin therapy

In line with UK paediatric type 1 diabetes guidance guidelines (NICE, 2023), KR was initiated on insulin therapy and was provided with comprehensive information on diabetes and its management, including carbohydrate counting. The initial insulin dose was set to be 0.35 times her weight (0.35×90=31.5 units/day), which was towards the lower end of the range for starting insulin dose (i.e. from 0.2 to 0.8 units/kg/day; Lemieux et al, 2010), taking into account her age and subcutaneous adiposity. KR was commenced on a multiple daily injection regimen: 15.75 units of degludec as basal insulin, with rapid-acting insulin aspart for bolus coverage using a 1:12 insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR) and a 1:5 insulin sensitivity factor (ISF). Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) was initiated with the FreeStyle Libre 2.

2. Weight management advice during hospital admission

During her admission, a dietitian conducted a comprehensive discussion on weight management. Her mother reported that KR has a substantial appetite, eats very frequently and prefers larger servings. Family therapy was deemed unsuitable owing to her father’s lack of receptiveness towards medical advice and lifestyle modifications. The primary concerns noted were the use of food as a reward or treat by one parent, overeating due to boredom, consumption of high-fat foods and a preference for unhealthy foods while not under supervision.

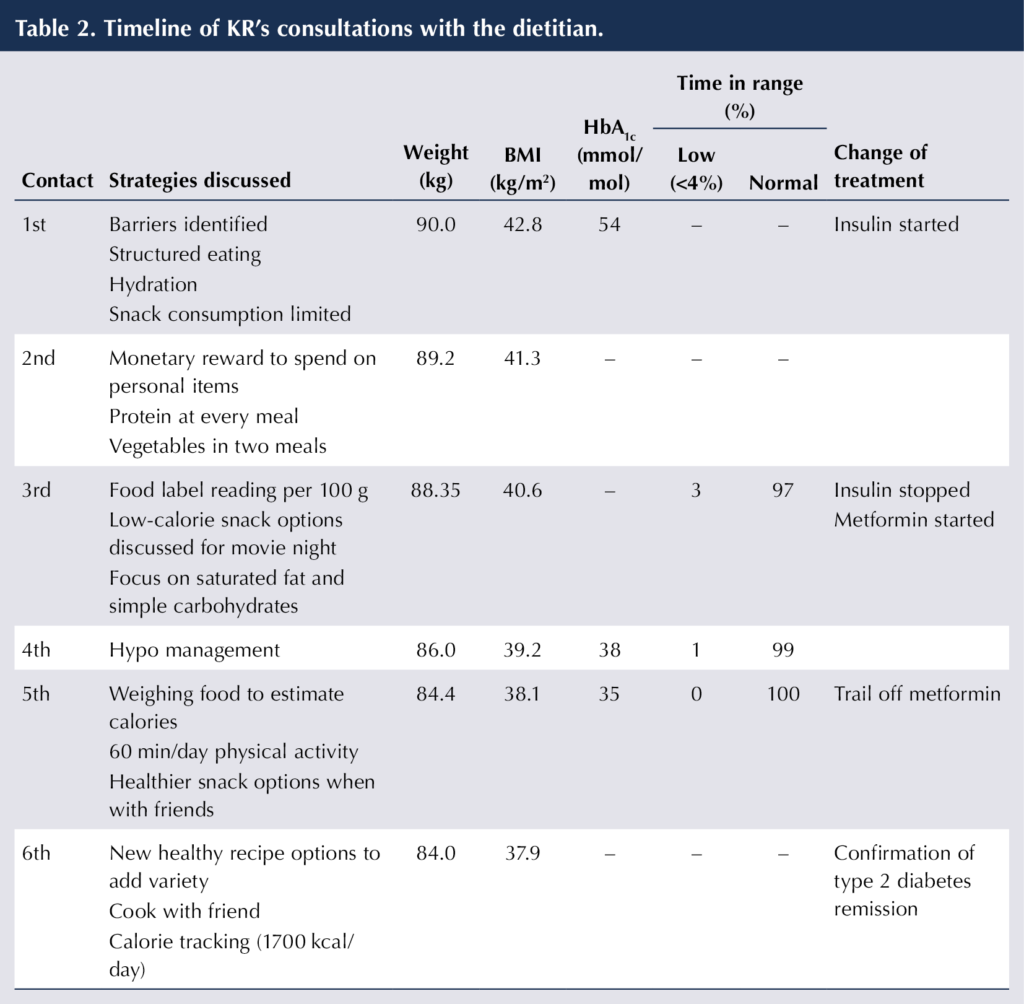

While waiting in hospital for autoantibody test results and confirmation of the diagnosis, a second meeting was held with the dietitian. Some initial goals were jointly agreed with KR and her parent to help KR with her excess weight. They were to establish a structured eating pattern, maintain proper hydration and to restrict snack consumption to a maximum of two per day (each containing maximum of 150 kcal). The reward system for food was replaced by shopping for personal items.

3. Discharge from hospital and awaiting confirmation of diagnosis

An outpatient appointment was agreed for 3 weeks’ time to work collaboratively on KR’s weight. It was reiterated that confirmed diagnosis of the type of diabetes would be based on the test results and, until then, type 1 diabetes management would be undertaken.

As a result of multiple episodes of hypoglycaemia, the total daily dose of insulin was consistently reduced, and KR was discharged with an ICR of 1:17, ISF of 1:5, and an insulin degludec dose of 12 units. Milk was to be drunk every night to avoid overnight hypoglycaemia.

At her third dietetic consultation, KR had actively implemented the changes that had been agreed and had lost 1.5 kg over 4 weeks. At this session the discussion revolved around the use of colour-coded labels (green, amber and red) to indicate the nutritional content per 100 g of food that she commonly used to consume. The importance of being cautious about the levels of saturated fat and sugars displayed on UK food labels (traffic light system) was explained. Cooking techniques were highlighted to her mother, with the thorough involvement and engagement of KR.

4. Therapy following confirmed diagnosis

The blood test results were received after 6 weeks, following a delay caused by the laboratory. No antibodies were found, which confirmed a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (Table 1). KR was started on the lowest dosage of metformin (500 mg once daily). Insulin was discontinued. However, KR’s mother reported hypoglycaemia (<3.5 mmol/L during activity). KR had not used finger pricking to monitor her blood glucose levels, but had relied on CGM. The use of chocolate bars or cookies for hypoglycaemia caused sudden spikes in her blood glucose levels, followed by a decline. The CGM system’s hypoglycaemia alarm, which was set at 4.5 mmol/L, was frequently activated during the night. This was subsequently lowered to 4.0 mmol/L. KR was advised to finger prick when the alarm was triggered and 15 minutes afterwards, and not to treat the hypoglycaemia unless it was <4 mmol/L using the finger-prick method. She was also made aware that the alarm could be set lower in the future when she may have gained confidence in her glucose control.

5. Intensive dietetic input for weight management

Her physical activities included walking to school, taking dog walks with a friend, using the gym at school once a week, dancing at home and swimming. She was encouraged to ensure at least 60 minutes of physical activity daily, and to continue to weigh all food.

It was discussed that fibre, vitamins and minerals should be considered when selecting meal options, not only calories. Healthier snack alternatives when going out with friends were discussed, including guidance on portion-controlled snacks such as dried fruit, alongside roasted nuts, fresh fruit and baked crisps. KR and her mother found the frequent dietetic visits of great value.

KR’s initial post-diagnosis HbA1c level was 38 mmol/mol and time in range (TIR) was 100%. Her BMI was now <40 kg/m2. A decision was made to discontinue metformin and to conduct her reviews remotely. KR and her mother were advised that remission can be achieved through consistent lifestyle modifications that keep blood glucose levels within range. KR did exceptionally well without any problems while being off metformin. After one month, her HbA1c had reduced to 35 mmol/mol, and her TIR was 100%. Since initiation of the intervention, KR had lost 5.5 kg (6.7% of her initial body weight) and her BMI had reduced by 11.5%. Postprandial blood glucose levels were consistently <8 mmol/L.

The application of the Libre 2 device was agreed for only 2 weeks before a scheduled clinic session to review her glucose levels. KR was growing weary of her limited selection of healthy dietary options. It was suggested she experiment with new recipes with familiar ingredients and to prepare meals with her friend. She was guided to establish a goal of consuming approximately 1700 kcal/day, using the MyFitnessPal app to track all food and beverage consumption. It was observed that offering precise instructions in quantifiable terms was a successful approach with KR. Consistently seeking guidance from a dietitian, establishing a limit of three objectives during each consultation and conducting follow-ups to overcome any barriers helped her maintain consistency and motivation. KR and her mother agreed to a review in 2 months. Once stability is achieved, follow-up can be extended to every 4 months, and so on.

Follow up and outcomes

KR successfully achieved a normal HbA1c within 16 weeks by substantially reducing her weight and BMI following her diagnosis. Goals were established with her consent, and adjustments were made collaboratively to address any perceived challenges. After a period of 3 months, not only had her HbA1c level lowered, but the secondary outcomes of ALT and lipid profile also showed improvement. The advised lifestyle changes were deemed durable and had a beneficial impact on her emotional well-being as well.

Discussion

The prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes in children is growing. In England and Wales, there was an 88% increase in the number of children aged 0–15 years receiving care from a paediatric diabetes unit between 2019/20 and 2023/24 (National Paediatric Diabetes Audit, 2025). Nutritional management might be a key to reducing the associated public health costs. The current weight management approach is inadequate, as evidenced by the increasing prevalence of obesity. Children and young people find it challenging to articulate the need for lifestyle modifications in the absence of any evident clinical indications or symptoms.

Hospital admission provides an excellent opportunity to work collaboratively with patient and family, and for the early introduction of an intensive weight management approach, with remission being more likely in the initial years after diagnosis (Kyi et al, 2023). The consideration that children are growing may result in a more precise indication for remission. This can be done by taking into account BMI instead of body weight. Weight loss of 10% within 5 years of diagnosis has been associated with remission, but a 6% reduction was observed in the present case alongside a reduction in BMI of 10.8%.

For sustainable weight loss, tailored lifestyle changes, including nutrition and physical activity, are necessary (Taylor et al, 2021). In addition to lifestyle interventions, short-term insulin therapy over six weeks may have contributed to beta-cell “rest” and functional recovery, potentially improving endogenous insulin secretion. While evidence in adolescents with type 2 diabetes is limited, similar physiological effects of early insulin therapy have been observed in adults, supporting the concept of beta-cell rest (Brown and Rother, 2008). When combined with reductions in subcutaneous fat achieved through dietary and physical activity strategies, this may enhance insulin sensitivity and support glycaemic improvement (Zhyzhneuskaya et al, 2019).

It is essential to continue regular monitoring of HbA1c and diabetes complications once remission has been achieved. There are no comparative studies on insulin treatment compared to alternatives in literature in children with type 2 diabetes. Therefore, well designed prospective randomised controlled trials in the paediatric population are needed to bridge this gap.

Acknowledgements

The completion of this undertaking could not have been possible without the participation and the consent of the young person, KR.

Written, informed consent was obtained from the participant in this study and the sharing of clinical data and information relating to the participant was allowed.

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this research.

Combined weight loss and sleep apnoea control yields better results than weight loss alone.

4 Feb 2026