“Our genes are a predisposition, but our genes are not our fate.”

Dean Ornish (2022)

This quote raises hope that we are not merely passive in our health journey. While our genetic predisposition is highly influential, it does not make an outcome inevitable. Yet, when you have a condition that is primarily blamed on lifestyle choices, it creates an expectation that you can be healthy if you just try. Becoming an active agent in one’s health does not mean being a free agent. Along with genetic and epigenetic influences, there are also invisible social, economic and environmental forces at work – the wider determinants of health. This leads us to the question: are all people equally able to control the risk in their lives?

While the perception of type 2 diabetes is often reduced to individual lifestyle choices, this oversimplification masks the systemic changes needed for health equity. For a comprehensive understanding of the condition, we must acknowledge the interaction between genetic, epigenetic, social and economic factors. This article invites healthcare professionals to take a broader view of understanding individuals with or at risk of type 2 diabetes.

The role of genes and epigenetics

If we use the analogy of a piano, as described by Klinghoffer (2012), the keys represent the genes we inherit. Epigenetics, then, is how the piano is played: the tempo, intensity and rhythm are shaped by early nutrition, trauma, stress and socioeconomic influences.

This means that someone may inherit a predisposition to type 2 diabetes (the piano keys), but external factors (the sheet music they are given and the way that music is played) influence whether those genetic risks are expressed. If the piano is out of tune, we do not blame the pianist for the sound the keys produce. In a similar way, we should not blame someone for the genes they have inherited.

Now consider the sheet music. Some individuals are handed complex, discordant scores that represent adversity, such as poverty, trauma or limited access to healthcare. Others may receive more predictable melodies, which represent more supportive conditions. The pianist’s ability to thrive depends not only on the instrument (their genes) and the music (their life circumstances), but also on the environment in which they perform, including social support, healthcare access and economic stability.

J.S. Bach famously said, “All one has to do is hit the right keys at the right time and the instrument plays itself.” The key phrase here is “at the right time”, emphasising the timing and context of environmental exposures that can activate or suppress gene expression. This highlights the delicate ebb and flow of life that shapes health outcomes.

Health is not shaped by individual effort alone. Just as a musician’s performance is influenced by how they interpret the score, a person’s health is affected by their resilience, support networks and access to resources. These factors can influence how genetic risks are manifested in health outcomes. Imagine a jazz ensemble: it is the interplay between the piano, saxophone and drums that creates that dynamic sound, not the piano player alone. In a similar way, by working together, we can create right conditions for people with type 2 diabetes to manage their health.

Trauma and adverse childhood experiences

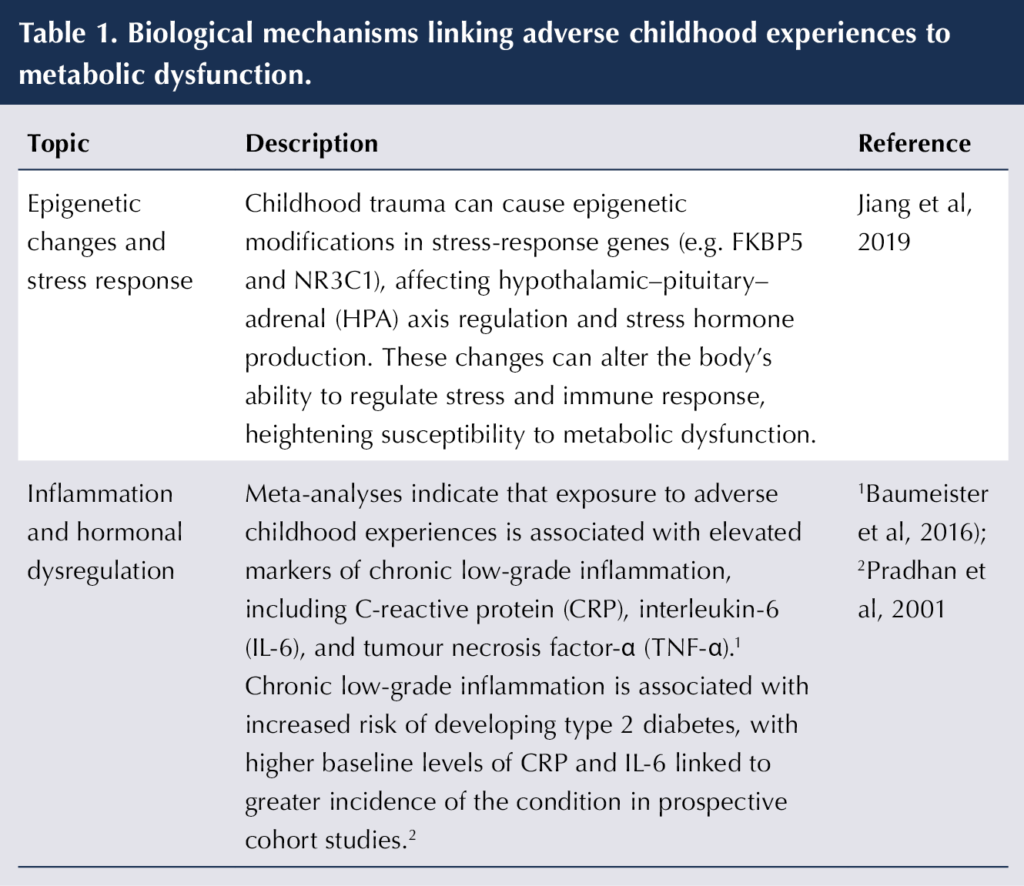

Type 2 diabetes is a frequently reported long-term condition in the presence of trauma in childhood (Senaratne et al, 2024). Traumatic experiences are associated with altered stress hormone regulation, increased inflammation and modified gene expression, which heightens susceptibility to metabolic disorders (Zhu et al, 2022; see Table 1). The impact of trauma is not just psychological; it can have lasting biological effects, such as affecting the body’s ability to regulate glucose and respond to insulin effectively.

Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score (2015) discusses this delicate relationship between the physical and psychological. It emphasises how traumatic experiences can disrupt the body’s ability to function normally. This can be likened to a pianist striking a wrong note or falling out of sync with the rest of the band.

An association between post-traumatic stress disorder and type 2 diabetes was observed in a large population-based sample after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, metabolic risk factors and other psychopathologies (Lukaschek et al, 2013). In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that approximately 28% of adults with type 2 diabetes experience depression (Khalidi et al, 2019). These findings do not imply that all individuals with type 2 diabetes have a history of trauma, but highlight how biological and psychosocial factors intersect to shape a person’s health.

Meet Leanna

Leanna, who has type 2 diabetes, arrived at our consultation concerned about her health. She opened with: “I am one of the naughty ones. I know it’s my own fault. I snack through the day – lots of crisps and savoury snacks. I know I shouldn’t.”

As we gently began to explore her diet and talk through some alternative food options, I asked about vegetable snacks. Her response revealed something deeper.

“I know it’s an excuse,” she began, “but when I was tiny, in a road accident, my grandmother died suddenly, and my mum was seriously hurt and in the hospital for a long period. During that time, I was cared for by relatives, and I remember being forced to eat vegetables to the point where I used to be sick.”

In that moment, it became clear that Leanna’s relationship with food was not driven by a lack of willpower or knowledge, but by trauma deeply rooted in early life experience.

The power of listening cannot be overstated. When people feel heard and understood, they begin to feel safe enough to explore their own patterns, motivations and barriers. This safety creates space for change.

Through our conversation, Leanna began connecting past trauma with current behaviours. This consultation was about meeting Leanna where she was, holding space for her pain and empowering her to take small, meaningful steps forward.

In an interview study by Christensen et al (2020), participants with type 2 diabetes described being more likely to go home and engage in unhealthy behaviours when their healthcare professionals took a moralising approach in consultations. When the entire weight of responsibility is shifted to a patient’s shoulders, it creates a new layer of pressure to withstand. We must consider that type 2 diabetes is a morally neutral topic, but it often becomes morally charged when it comes to deciding how much responsibility patients hold.

Leanna’s story reminds us of how deeply personal experiences intersect with wider social realities. Aside from trauma, these invisible burdens – poverty, poor housing, education and job insecurity, – form the wider determinants of heath and shape health choices every day for millions of people.

The role of poverty and access to healthy choices

While public health messaging emphasises personal responsibility for “healthy choices”, the reality is that choices are shaped by circumstances. Individuals living in poverty often face significant barriers to maintaining a “healthy lifestyle”, including:

- Limited access to affordable, nutritious food (e.g. food deserts and high-cost fresh produce).

- Unstable housing, poor home conditions and unsafe neighbourhoods.

- Reduced access to healthcare and diabetes education, and delays to diagnosis and treatment.

- Increased exposure to chronic stress.

- Low-wage, shift-based or precarious employment leading to financial insecurity (Walker et al, 2014).

For many, type 2 diabetes is not simply a result of personal behaviour, but a consequence of structural inequalities that shape everyday living conditions. For example, a person with two jobs may opt for a ready meal instead of cooking from scratch owing to their limited time and energy at the end of the day.

Effectively addressing diabetes means recognising and tackling the barriers people face. On average, individuals with diabetes spend only three hours per year with their healthcare team, yet half of people with diabetes have missed medical appointments due to fear of stigma (Diabetes UK, 2022). We need individuals to attend their appointments, and we must ensure that each interaction is meaningful – leaving people feeling understood, supported and empowered to manage their own care. Without this, we make little progress.

Trauma-informed communication tips

Opening the conversation

Start with warmth and openness: e.g. “How are you?”, then truly listen for two minutes without interrupting.

Avoid jumping straight to clinical details. Let the patient set the pace. If you find yourself speaking more than them, take that as a cue to pause. Stop talking and listen. Create space for the patient to express themselves fully.

Exploring experience safely

Ask permission before discussing sensitive topics: “Would it be okay if we talk a bit about how stress affects your health?” Respect boundaries and watch for distress.

Acknowledging emotion

Validate what you hear: “That sounds really tough – thank you for sharing that with me.”

Offering choice and collaboration

Give patients control, where possible: “Would you prefer to talk about food choices today or focus on medication?” Choice restores autonomy and builds trust.

Encouraging self-efficacy

Highlight strengths: You’ve already made great progress – what’s helped you get this far?” This reinforces positive coping and agency.

Build a folder of local support resources to share with patients. For example, social prescriber referral to address loneliness, or a housing support officer for help with housing and rent arrears.

Avoiding stigma and blame

Use neutral, supportive language: “Your blood glucose has been higher lately”, rather than “You’ve not been controlling it.” Words shape safety and self-worth.

Checking for distress

Notice changes in body language or tone. Pause and ask: “I can see this might be hard to talk about – would you like a moment?”

Closing the consultation

End with clarity and reassurance: “Is there anything you’d like me to note for next time?” Affirm progress and give hope. Use your electronic patient record system to note trauma-informed approaches that work for specific individuals.

Reflective practice prompts

After the consultation, ask yourself: “Did I make space for the patient’s story?” and “Did I assume or ask?” Use this to refine your trauma-informed habits. Upskill using training resources and documents (Box 1).

Summary

Going back to the question posed earlier, “Are all people equally able to control the risk in their lives?”, the evidence and stories explored here make it clear that they are not. Yet small, deliberate changes in how we communicate can help narrow this gap. By adopting trauma-informed approaches, we create the conditions in which individuals feel heard, respected and empowered to engage with their health. While we cannot alter a person’s genetic inheritance, we can influence the social environments that shape gene expression and behaviour.

| Box 1. Training and resources for healthcare professionals. |

| Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center Resources to support organisations adopting a trauma-informed approach. Available here Trauma-informed practice: A toolkit for Scotland Toolkit to support organisations, departments and teams in planning and developing trauma-informed services. Available here Trauma informed care A suite of sessions promoting trauma-sensitive practice in health and social care. Available here Language Matters: language and diabetes Guide providing practical examples of language that will encourage positive interactions with people living with diabetes. Available here End Diabetes Stigma Pledge your commitment contribute proactively to end diabetes stigma and discriminations. Available here Personalised Care Institute NHS England initiative to help staff develop the knowledge and skills to support implementation of the NHS Long Term Plan and the Comprehensive Model for Personalised Care. Available here Introduction to prehabilitation, rehabilitation and personalised care and support for people living with long-term conditions Evidence-based e-learning to develop knowledge and understanding. Available here |

Combined weight loss and sleep apnoea control yields better results than weight loss alone.

4 Feb 2026