The NICE NG18 guideline on diabetes management in children and young people (CYP) was updated in December 2020, to provide new advice on fluid therapy for those with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). The new guidance takes into account recent evidence on the appropriate route, type, and rate and volume of fluids to use for rehydration, and clarifies areas that had previously caused confusion. In this short report, we outline the key changes to the guidance and the reasons for them.

Route of administration

There is no evidence comparing different routes of administration or different oral fluids for hydration, so the guideline committee has updated the recommendations based on its experience and expertise. The update keeps the previous recommendation that DKA should be treated with intravenous (IV) fluids and insulin if the CYP is not alert, is nauseated or vomiting, or is clinically dehydrated.

Oral fluids should not be given unless ketosis is resolving (blood pH has reached 7.3) and the CYP is alert and is not nauseated or vomiting. The decision to stop IV fluids and switch to the oral route should be discussed with the responsible senior paediatrician if the CYP still has mild acidosis or ketosis. Specific recommendations on oral fluids have not been made owing to lack of evidence.

Total fluid requirement and administration rates

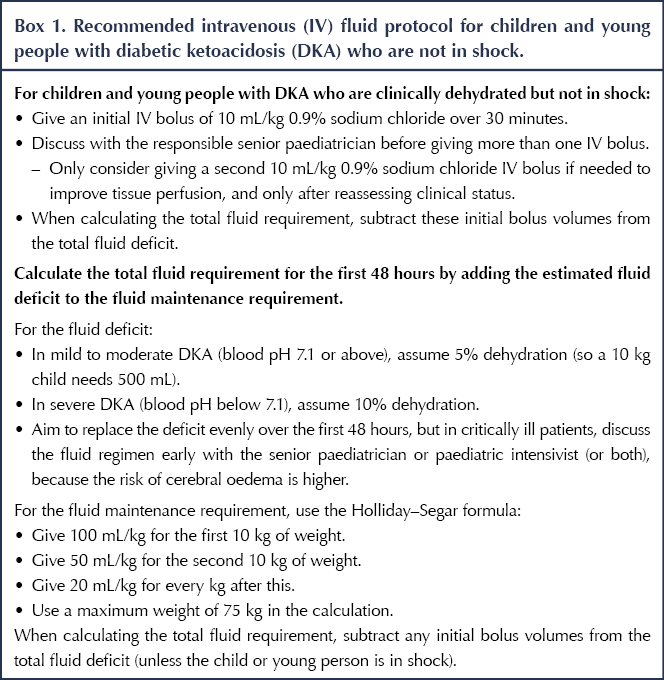

In the previous version of the guideline, the rate of fluid administration was restricted because rapid fluid administration was believed to cause cerebral oedema. Previous hypotheses were that rapid administration of IV fluids could reduce serum osmolality, resulting in brain swelling. However, new evidence, particularly from the PECARN DKA FLUID trial (Kuppermann et al, 2018), suggests that brain injury in this group may be caused by DKA itself, due to cerebral hypoperfusion, reperfusion and neuroinflammation. Thus, CYP would benefit from receiving more fluids in the first 48 hours than was previously recommended. In light of this, the guidance has been updated to use more rapid fluid administration, including fluid boluses (see Box 1).

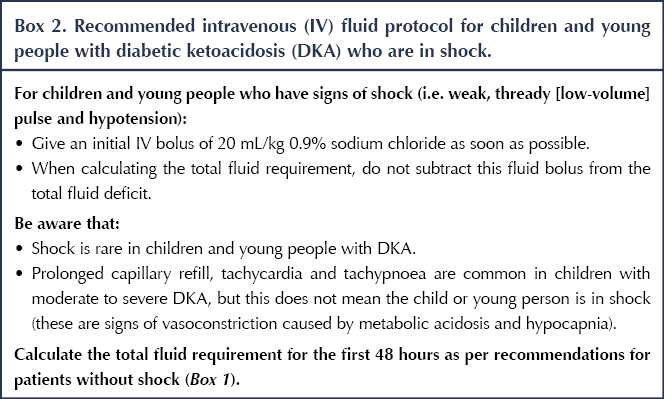

Separate recommendations have been made for CYP who are in shock, as this group needs a higher volume of fluids given more rapidly (See Box 2).

The recommendation for calculating fluid maintenance requirement was amended to include the Holliday–Segar formula. This formula has been shown to be safe, with no adverse events, and is commonly used in practice, as well as being endorsed by ISPAD and BSPED in their guidelines.

The new recommendations provide a more balanced approach for calculating the total fluid requirement. However, caution must be taken when calculating the fluid requirement for CYP who are obese. A maximum weight of 75 kg should be used when calculating fluid requirements for these individuals, to avoid excessive fluid administration and to minimise risk.

Type of fluids

The original recommendations on the type of fluids to administer remain the same: 0.9% sodium chloride should be used, without added glucose, for both rehydration and maintenance fluid until plasma glucose is below 14 mmol/L. Once glucose falls below this level, fluids should be changed to 0.9% sodium chloride with 5% glucose and 40 mmol/L (or 20 mmol/500 mL) of potassium chloride.

Potassium

Guidance on the use of potassium is based on expert opinion. More detail has been added about caring for CYP with anuria or potassium levels above the normal range. It is essential not to delay adding potassium to fluids, because the administration of insulin and correction of acidosis drive potassium into the cells and can lead to a fall in potassium levels, which can lead to cardiac arrhythmias and death.

For CYP with potassium levels above the normal range, only add 40 mmol/L (or 20 mmol/500 mL) potassium chloride to their intravenous fluids if:

- Their potassium is less than 5.5 mmol/L,

or - They have passed urine, which gives assurance that they do not have renal failure.

For those with hypovolaemia at presentation, potassium chloride should be included in IV fluids before starting the insulin infusion.

Sodium

Recommendations have been added on monitoring sodium levels. Serum sodium levels should be monitored throughout DKA treatment, and the corrected sodium should be calculated initially to identify hyponatraemia.

When monitoring serum chloride levels, be aware that serum sodium levels should rise as DKA is treated and blood glucose falls, and that falling sodium is a risk factor for cerebral oedema. However, a rapid and ongoing rise in sodium may also suggest possible cerebral oedema, caused by the loss of free water in the urine.

Hyperchloraemic acidosis and sodium bicarbonate

New recommendations highlight the complication of hyperchloraemic acidosis, defined as a persisting base deficit or low bicarbonate concentration despite evidence of resolving ketosis and clinical improvement. Clinicians should be aware that some CYP may develop this, but that it resolves on its own over time and specific management is not needed.

The evidence does not favour the use of sodium bicarbonate as an additive to IV fluids, and so this should not be done routinely. However, a small number of CYP with DKA can exhibit compromised cardiac contractility caused by life-threatening hyperkalaemia or severe acidosis. Such individuals may benefit from intravenous sodium bicarbonate, although this decision should be discussed with the paediatric intensivist.

Helping homeless adults to overcome the challenges of managing their condition.

16 Apr 2024