Help Madina is a charity working to provide healthcare access for people who live in the city of Makeni and village of Madina in Sierra Leone. The charity is seeing an increasing number of people with diabetes, and reached out to the DSN Forum UK to help assemble a team to provide much-needed education and raise awareness with local healthcare teams and communities.

The challenges of providing healthcare

The DSN Forum UK and Help Madina created a diabetes team made up of a diabetes nurse (Amanda Epps), a dietitian (Elaine Allerton), a podiatrist (Helen Towers), a GP (Veronica Sawicki) and a medical communications advisor (Lisa Kelly) to visit Sierra Leone.

During our visit, we learned a great deal about life in Sierra Leone. Situated on the south-west coast of West Africa, it is a small but densely populated country, with a growing population of over 7 million people from approximately 18 ethnic groups. Around 56% of the population live in rural settings, often in small villages with modest houses made from mud bricks and with tin roofs. Most of the dwellings have no electricity or running water, and no inside toilet. Water is collected daily from local wells provided by charitable organisations, such as WaterAid and Help Madina. The climate is tropical, so temperatures can be extreme. While we were there they reached 40 °C, with the humidity making it feel like 45 °C.

Sierra Leone is one of the poorest countries in the world. In its efforts to develop economically, it has faced many challenges. Medical care is not readily accessible, with doctors and nurses being out of reach for many villagers.

Civil War

The country experienced a civil war from 1991 to 2002, which left a trail of devastation in its wake that is still very visible. During our visit, we noted that there are still many burnt-out houses and a lot of government buildings remain in a state of disrepair. Limb amputation was used as a weapon of war, with the aim of obstructing people’s ability to vote (Mitton, 2015). We saw many people who had suffered horrific mutilation in this way.

Ebola

The 2014–2016 Ebola virus crisis in West Africa caused further distress. Sierra Leone was one of the hardest-hit countries during this epidemic. The already fragile healthcare system was quickly overwhelmed by the influx of cases. Military intervention to enforce quarantines and control the outbreak was required (Fang et al, 2016).

Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS

Sierra Leone has one of the highest tuberculosis (TB) burdens in the world, with a prevalence that greatly exceeds the global average (Lakoh et al, 2020). It also has a high prevalence of HIV/AIDS, which further complicates efforts to control TB (Babawo et al, 2020). Poverty, and the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV/AIDS, often hinder access to HIV prevention, testing and treatments.

Water, sanitation and cholera

Sierra Leone faces considerable challenges related to water and sanitation infrastructure (Fayiah, 2024). Many communities lack access to clean water and adequate sanitation facilities, forcing people to rely on contaminated water sources, such as rivers, streams and shallow wells.

Poor hygiene practices increase the risk of cholera transmission. Cholera outbreaks in Sierra Leone have a significant public health impact, leading to high morbidity and mortality rates, especially among vulnerable people, such as children, the elderly and those with weakened immune systems (Charnley, 2022).

Drug addiction

Drug addiction is a big problem (Bangura, 2024), with a national emergency being declared in April over the use of a drug named “kush”. Locals say it is a mixture of high strength cannabis, leaves soaked in acetone, tramadol and, some say, human bones. The emergence of this new trend has had a profound effect on the youth of Sierra Leone. Social media platforms are inundated with images and videos depicting individuals in a zombie-like state and visibly malnourished because of excessive consumption of kush.

Food poverty

Sierra Leone is afflicted by food poverty (Volz, et al 2020). Its economy is heavily reliant on agriculture, yet productivity remains low owing to factors such as a reliance on rain-fed agriculture, limited access to modern farming techniques, and inadequate infrastructure for transportation and storage. Many households struggle to produce enough food to meet their nutritional needs. Additionally, Sierra Leone is prone to adverse climatic events, such as drought, floods and erratic rainfall patterns, which can disrupt agricultural production and exacerbate food insecurity (Bonuedi et al, 2022).

Traditional herbal medicine

Lack of funds to access mainstream healthcare means that many people resort to using local herbal remedies. We were told that many of these treatments are harmful, causing burns, blindness and even death. Furthermore, without access to medications such as antibiotics and insulin, the original illnesses remain untreated.

Type 1 diabetes care

People with type 1 diabetes, which often affects children but can impact individuals at any age, require insulin to live (Holt et al 2021). People in low- and middle-income countries continue to die due to insufficient insulin (Mbanya and Mba, 2021). Until last year, there was no sustainable access to insulin in Sierra Leone.

Type 1 diabetes is a death sentence for most, with individuals surviving for a few months on a diet of boiled mango leaves. Images of children in Sierra Leone with type 1 diabetes have been likened to those of children in the 1920s before insulin was invented – skeletal, frail and comatose. We were told that the advice given by some healthcare professionals is to starve the person with type 1 diabetes of all carbohydrates, so that they may live a little longer. Dr Veronica Sawicki has witnessed a child die in diabetic ketoacidosis owing to a lack of insulin – an awful experience that led her to contact the DSN Forum UK team to ask for support.

Type 2 diabetes care

Type 2 diabetes prevalence is increasing in sub-Saharan Africa (Motala et al 2022). It would seem, however, that local people have not been sensitised to diabetes, and many do not know what it is or what the symptoms are. Furthermore, lack of funds means that people will not go to a doctor until their symptoms are severe or they have developed a complication of the condition, such as eyesight problems or a foot wound.

We found that foot wounds were a big problem in Sierra Leone. The shortage of antibiotics, appropriate dressings and offloading equipment, together with the extreme heat and inadequate nutrition, mean that small ulcers can quickly become septic and life-threatening. Lacking access to sterile dressings, if an ulcer develops, many people use cloths, newspapers or leaves. Traditional herbal remedies also often lead to worsening wounds, with catastrophic consequences.

Access to type 2 diabetes treatments is difficult. The team in Makeni had access to metformin and glibenclamide. However, the cost of providing a 1 g dose of 500 mg metformin twice daily for a month is the equivalent of about £4.50. A full-time nurse in the country earns around £83 a month, and rice to feed a family costs around £40. Medication is not, therefore, a priority when food and basic life essentials are not affordable.

Prior to the visit

Before the educational visit, the DSN Forum UK had many meetings with Help Madina to establish the problems that needed addressing and to help devise solutions. One concern was the lack of insulin. This was the top priority for the charity as, up until now, Dr Sawicki had been collecting unused, in-date insulin from people who no longer required it and delivering it herself in suitcases on her visits to the country. The DSN Forum UK ran a social media campaign to obtain more for Veronica to take with her, and managed to collect 50 kg of insulin for her last visit in March 2023.

By no means was this ideal, as the supply was intermittent, the insulin available varied from month to month and it all relied on her being able to get to Sierra Leone before previous stocks ran out. This was a particular issue during the Covid-19 pandemic, when flights to the country were grounded 12 months. This compromised the cold chain, meaning as insulin degrades outside fridge temperatures. In Sierra Leone, however, it was this insulin or no insulin.

We needed a safer, more reliable supply of insulin, so the team suggested contacting Life for a Child and Insulin for Life. These charities now provide insulin to the Holy Spirit Hospital in Makeni, making it one of the only hospitals in the country that has available and free access to this life-saving medication. Life for a Child also supplies blood glucose meters, test strips and GlucoTabs for those with type 1 diabetes who are under 30 years of age.

Planning the visit

The DSN Forum UK team used social media to gather and develop a task and finish group to help plan what would be required to support the Help Madina team. We had over 25 professionals, including diabetes nurses, podiatrists and dietitians, brainstorming ideas. We owe a big thank you to PITstop diabetes, who allowed us to adapt their resources for the local team. We provided educational material in easy-to-read formats, such as posters, to raise awareness of signs and symptoms, easy exercises, diet advice, and so on.

We decided that the greatest benefit would result from devising a team of healthcare professionals who could visit the team in Sierra Leone to see the issues first hand. The cost of flights and accommodation for a small team soon reached over £9000, but we secured a grant of £5000 from The TransPetrol Foundation and the rest was self-funded.

During the visit

The first day in Sierra Leone was a Sunday, so we followed the local custom and went to church. The diabetes nurse had arranged for us to stand at the front and introduce ourselves. The congregation was very receptive and welcoming, and had many questions about diabetes, signs, symptoms and causes.

Over the next few days, we gave five education sessions to the hospital team:

- Introduction to diabetes

- Complications of diabetes

- Nutrition

- Footcare

- Insulin safety.

The hall was filled with staff every time we gave a lecture, showing just how keen these healthcare professionals are to learn.

Following these sessions, we taught the diabetes team about carbohydrate counting. This was a new subject to them as, previously, the treatment for type 1 diabetes had been an extremely restricted diet.

We were also lucky to have had lots of diabetes equipment donated, including glucose-testing kits and ketones strips. When a child arrived looking very much like they were in DKA, we were able to test their ketone level (which was 4.4 mmol/L).

We also had 24 FreeStyle Libre sensors donated to us. I managed to get four readers, as I thought people would be able to use them with their phones. We subsequently discovered, however, that the app is not available in this Sierra Leone. We also had some slight problems with the sensors staying on in the heat, but I had prepared for this by buying some Skin Tac.

As well as providing education, the team spent six days in the Holy Spirit Hospital’s diabetes clinic seeing as many of the patients on the caseload as possible. Our podiatrist, Helen, spent a lot of time dressing wounds and showing the local wound care team how to manage diabetic foot ulcers. This included using alterations to people’s flip-flops as an example of how to offload pressure.

We also updated the local diabetes guidelines, while being mindful of the skillsets and equipment available. Much our guidance was, therefore, based on that already used in low- to middle-income countries.

We met the pharmacist to see if there was a way to obtain newer medications locally. However, this was not possible, as they are not available nationally.

We gave the local diabetes association ideas on how it could improve its work, showing them what Diabetes UK are doing and suggesting initiatives that could be run without funding.

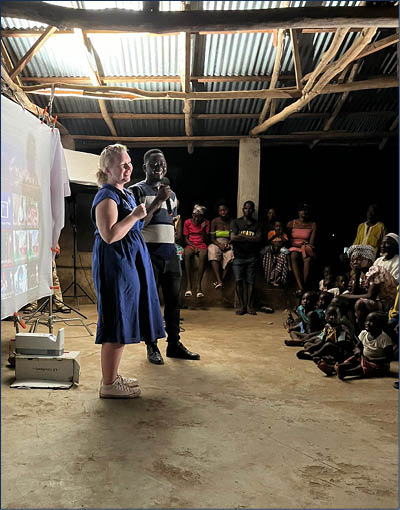

Visiting a small village just outside Makeni, we arranged for a public showing on a big, solar-powered screen of a documentary (that you can watch here) about recognising diabetes signs and symptoms, and followed it with a Q&A session. We also worked with the film-makers to help write a script for a film about type 1 diabetes in Sierra Leone.

Travelling to Madina, we then met the Elders of the village to update them on what we had planned. We ran a diabetes screening event, which we advertised on local radio the night before in four of the local dialects. Eighty-four people attended, five of whom were found to have type 2 diabetes. Three received diet and lifestyle advice, while the other two had blood glucose levels above 20 mmol/L and required starting on medication.

Future plans

A social media campaign has raised over £2848 which, with Gift Aid of £678.75, gave a total of £3526.75. This money will be used to set up a new diabetes and hypertension clinic in Madina. From the UK, we will be mentoring the team using virtual training and multi-disciplinary sessions. We are also looking for funding to send another team to Sierra Leone in November 2025.

The whole experience was both moving and rewarding, and has highlighted the incredible work of the charities that are supporting people with diabetes.

For further information, visit our JustGiving page and the Help Madina website.

Developments that will impact your practice.

22 Dec 2025