Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, is associated with a devastating but largely preventable complication; it is the leading independent risk factor for stroke, being responsible for up to one third of all cases. Stroke related to AF is associated with higher mortality and disability than other strokes, due to the large clots which embolise from the heart; indeed, two thirds of patients die within one year of a stroke due to AF (Lin et al, 1996).

Comorbidity is common in AF and not only increases the risk of stroke but also the risk of bleeding from anticoagulation treatment. Hypertension, heart failure (which is a common cause and effect of AF), vascular disease, previous transient ischaemic attack/stroke and diabetes significantly increase stroke risk in people with AF. All people with AF who have even a single one of these comorbidities or who are aged 65 years or over are likely to benefit from anticoagulation treatment (Lip, 2017).

The lifetime risk of developing AF from the age of 40 is in the region of 1 in 4 for both men and women (Lloyd-Jones et al, 2004). Sadly, about half of AF-related strokes occur in people who were not previously diagnosed with AF (Cerasuolo et al, 2017). It is therefore important to opportunistically screen for AF in people who are at risk of developing the condition. Patients aged over 65 years and with diabetes and/or hypertension are at particularly high risk, and even higher risk if there is evidence of micro- and macrovascular disease (e.g. those with active diabetic foot disease).

Screening for AF in clinic

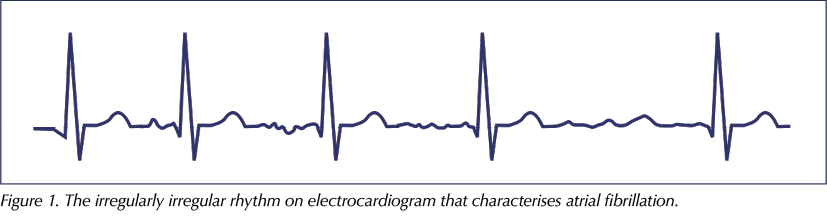

Screening for AF can be rapidly and effectively achieved in clinic with a simple pulse check (Fitzmaurice et al, 2007), and this should be an integral part of any diabetes review. If the pulse is regular, persistent AF is effectively ruled out. Those with an irregular pulse, characteristically irregularly irregular (Figure 1), should proceed to electrocardiography (ECG) to confirm or refute the diagnosis of AF. Once AF is confirmed, full anticoagulation can be achieved within 3 hours of treatment initiation in the case of the direct oral anticoagulants. Anticoagulation in the setting of AF is one of the most effective treatments in medicine and reduces the risk of stroke by 65–70%.

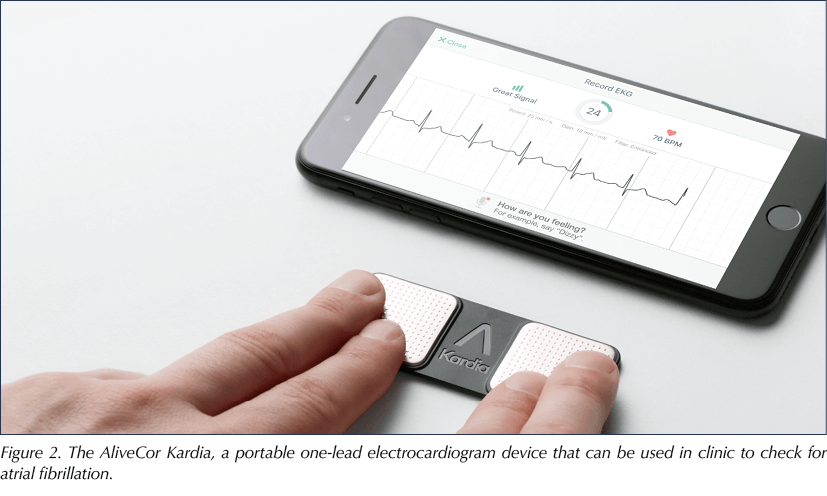

Portable one-lead ECG devices, such as the AliveCor Kardia (Figure 2), are increasingly being used to screen for AF in a clinic setting and offer a high degree of sensitivity and specificity for the condition. The device can be paired to a compatible phone or tablet, which creates a ECG trace in PDF format that can be uploaded into the notes.

Summary

In summary, it is critically important to screen for and identify the potentially lethal comorbidity of AF in people with diabetes, as this confers a more than five-fold increase in the risk of stroke. A simple pulse check or use of a portable one-lead ECG device can effectively screen for AF in clinic, and is key to addressing the huge burden of avoidable catastrophic strokes and their massive downstream effects on health and social care systems, as well as the human costs.

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025