The successful prevention of diabetes-related complications is an increasing problem for healthcare planners. The prevalence of diabetic foot ulceration is estimated to be between 4% and 10% of all people with diabetes (International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot, 1999). Research shows that, in the developed world, 50% of non-traumatic lower-limb amputations occur in the 4% of the population who have diabetes (Reiber et al, 1992). In up to 85% of people with diabetes who undergo lower-limb amputation, ulceration precedes that intervention (Pecoraro et al, 1990)

The causal pathway to lower-limb amputation in diabetes is multifactorial, but not inevitable. The triad of neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease and infection are well recognised precursors to diabetes-related amputation (Boulton et al, 2005). There are many opportunities for people with diabetes and the healthcare system to intervene along this pathway and reduce the number of amputations.

Footwear has been implicated in diabetic foot ulceration in 21% of cases (Macfarlane and Jeffcoate, 1997). Providing people with custom-made footwear to accommodate foot deformities and redistribute plantar pressures offers the opportunity to reduce the incidence of foot ulceration. The reulceration rate in people with previous diabetic foot ulceration is 40% (Pound et al, 2005), and the provision of specialist footwear is one of the tools in the diabetic foot clinic’s armamentarium to reduce this. However, compliance with the supplied footwear is often poor, with only 22% of people in one study reporting that they wore their shoes regularly (Knowles and Boulton, 1996).

The cost of providing specialist footwear varies depending on the complexity of the prescription, from stock to bespoke; in the authors’ service prices for a pair of specialist shoes range from £100 to £363. The estimated cost of healing one diabetic foot ulcer is £5200 (Ramsey et al, 1999). While high as a one-off cost, the cost of specialist footwear should be looked at in light of the cost of amputation, which the 2008/9 Payment by Results tariff is £11031 (non-elective amputation; Department of Health, 2007). Clearly, specialist footwear to prevent reulceration can be cost-effective.

Diabetic footwear service

The multidisciplinary diabetic foot clinic within the Elsie Bertram Diabetes Centre serves a population of 32000 people with diabetes. The clinic has annual activity levels of >4500 contacts and >700 new patient referrals.

Specialist podiatrists in this centre are the sole gatekeepers for the provision of hospital footwear for people with diabetes. Over the past 10 years the eligibility for footwear has tightened. Hospital footwear is now restricted to people with significant foot deformity that cannot be accommodated in an off-the-shelf shoe. People who fall outside this group are given both verbal and printed information and advised to purchase their own shoes. Prior to this, specialist footwear was provided to all those with any history of diabetic foot ulceration.

The clinic has a specialist shoe fitter working alongside the podiatrists twice weekly. The clinic offers stock, modular stock and bespoke footwear. Only 19% of the shoes provided are bespoke; the remaining 81% are stock or modular stock, examples of which are shown in Figure 1. Stock and modular stock come in 34 different styles for women (24 shoes; 10 boots) and 21 for men (12 shoes; 9 boots). All styles are available with either lace or velcro fastening.

People fitted for shoes are shown the catalogue of available styles and swatch samples and discuss their prescription with the shoe fitter. The important components of footwear design for ulcer prevention are:

- Adequate depth to accommodate deformity and insoles.

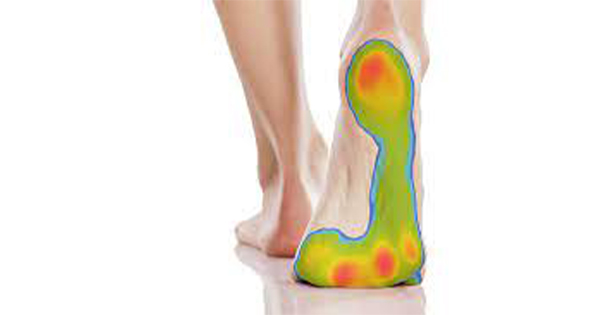

- Reduction of plantar pressure.

- Low opening front.

- Soft collars.

- Microfibre lining to forefoot as minimum.

- Minimal seams away from toes and joints.

- Microcellular sole.

- Soft upper,

- Fastening.

The type of offloading provided is dependent on individual requirements. As a minimum, a 6-mm thick poron inlay is provided and can be covered with memory foam to provide additional cushioning. People requiring more aggressive offloading can be cast for total-contact insoles, which are manufactured in soft- or medium-density ethylene vinyl acetate. External rockers are often provided to people with limited joint mobility.

The need for specialist footwear is factored into treatment plans at the clinic to ensure that once ulcer healing is achieved, people receive their footwear quickly and can be discharged into the care of community podiatry services. Under the current agreement, people in this group are entitled to receive two pairs of shoes per annum and have access to a shoe repair service. People may arrange an appointment with the shoe fitter as necessary, either for repair, alteration or replacement.

Aim

The aim of the study was to assess patients’ perceptions of the shoe-fitting service provided at the Elsie Bertram Diabetes Centre.

Method

A questionnaire was devised in collaboration with the Clinical Governance and Audit Department (Appendix I). This was originally distributed in 2001 and again in 2010. On both occasions, respondents were identified from the shoe-fitting company’s sales ledger for the preceding 2 years; this list was then cross-referenced with the hospital’s patient administration system. People who were untraceable, had relocated or had received only orthotics were excluded. A total of 100 individuals were then randomly selected from this list by the administration team.

The questionnaire was posted to respondents, together with a pre-addressed stamped envelope for return the completed questionnaire. In 2010, in addition to the 100 posted questionnaires, people who had a pre-existing appointment with the podiatrist were given the questionnaire, with the pre-addressed envelope, when they attended the clinic. This in-person provision of the questionnaire enabled the 2010 sample size to be slightly larger than that of 2001.

Results

Of the 100 people surveyed in 2001, 45 replied, giving a response rate of 45%. In 2010, 71 of the 124 people invited replied, giving a response rate of 57%. Not every respondent completed every question and actual numbers are supplied.

The service achieved consistently high levels of patient satisfaction, as evident from the of respondents rating their experience with the shoe-fitting service as either “very good” or “excellent” maintained at 95–6% across the two questionnaires (2001, 40/42; 2010, 67/70). Ninety-seven per cent (68/70) of respondents in 2010 felt that they were given adequate information as to why they were being provided with specialist footwear.

Across the two questionnaire cohorts, 90% (100/111; 37/41 [2001] vs 63/70 [2011]) of respondents rated the shoes provided as ≥4 for comfort (1 being very uncomfortable, 6 being extremely comfortable; Figure 2).

The proportion of respondents who wore their shoes all the time/everyday rose from 64% (29/45) in 2001 to 76% (54/71) in 2010 (Figure 3). In 2001 no respondents reported that they never wore their shoes; in 2010 this had risen to 4% (3/71). The reasons stated for this were a dislike of the appearance of the shoes and, in one case, a problem with fit.

The range of colours offered by the service has increased between 2001 and 2010. This was reflected in responses to the question of whether respondents felt they were given a choice of colours: 89% (40/45) answered “yes” in 2001, which rose to 99% (66/71) in 2010 (Figure 4). The most popular colour for men is black, and for women black or mushroom. The two style ranges are equally popular.

The turn-around time for providing shoes improved: in 2001, 79% (22/28) of pairs were ready in ≤1 month, and by 2010 this had risen to 98% (42/43). The number of respondents using the repair service also increased over time, rising from 55% (24/44) in 2001 to 64% (44/69) in 2010.

Discussion

The response rate for this questionnaire was good in both 2001 (45%) and 2010 (57%).

Compared with a similar study (Knowles and Boulton, 1996), the percentage of people who reported wearing their specialist footwear all the time was higher in the present cohorts, increasing from 64% in 2001 to 76% in 2010. However, a major limitation of self-report questionnaires is that it cannot be known whether the answers given are a true reflection of how often respondents actually wear their specialist footwear. Despite this, the reported increase in footwear compliance could reflect greater acceptability of the shoes as a result of greater style and colour choice (17 new colours and 13 new styles in the intervening period). The appearance of specialist footwear appears to have been highly acceptable to the 2010 cohort, with <3% of respondents not wearing the supplied shoes because they did not find them cosmetically acceptable.

Improved compliance over time may also be a factor of the tightening of specialist shoe eligibility criteria in the period between the two surveys. Only people with significant foot deformity that cannot be accommodated in an off-the-shelf shoe were eligible for specialist footwear in 2010, perhaps meaning that this group had fewer alternatives than those who received shoes in 2001.

While the percentage of overall footwear compliance increased between 2001 and 2010, there was also an increase in the number of respondents who reported never wearing the specialist shoes (none in 2001, 4% in 2010). Although the service stresses the importance of wearing the footwear, the questionnaire revealed that at least three pairs of shoes were provided to respondents in the 2010 cohort that were never worn, wasting valuable resources.

The majority of respondents rated their shoes as ≥4 (1, very uncomfortable; 6, extremely comfortable). However, it was not possible to cross-reference comfort ratings with the presence or absence of neuropathy in the respondent.

The questionnaire revealed that, overall, 82% (93/114; 13/69 [2001] vs 8/45 [2010]) of people issued with hospital footwear reported that they had never experienced any problems with their shoes, leaving 18% (21/114; 13/69 [2001] vs 8/45 [2010]) of respondents who had. However, whether these were problems of fit, comfort or the development of new lesions was not investigated. This question will be expanded to include these details.

Over the past 10 years, the percentage of people using the repair service increased. After the 2001 questionnaire delivery, and before the 2010 questionnaire, the service introduced written information on taking care of specialist footwear, which included the repair service. This is the likely cause of the increased the use of the repair service.

Conclusion

The footwear service at the Elsie Bertram Diabetes Centre has achieved consistently high levels of patient satisfaction, and improvements in patient-reported footwear compliance have been seen. The next step in evaluating the service will be a clinician-led prospective study following new referrals to the footwear service, which may help to answer some of the questions and criticisms of this study.