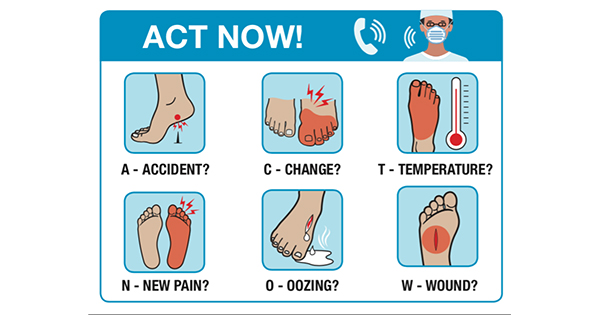

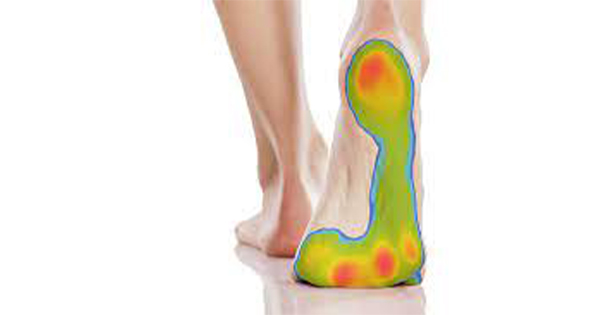

Offloading plantar pressure is a mainstay of treatment for neuropathic foot ulceration. A range of pressure offloading modalities are used in clincial practice, including total-contact casting (TCC) and felt padding (FP; Figure 1).

Research evaluating the benefits of offloading in the management of neuropathic foot ulcers primarily focuses on time to healing, healing rate and impact on plantar pressures. Aspects such as patient satisfaction with treatment and the impact selected offloading regimens may have on quality of life, remain relatively unexplored. Attending to the impact of clinical treatment on patient-centred outcomes, including satisfaction, allows for balance between favourable clinical outcomes and the individual’s quality of life during treatment.

This pilot study investigates whether differences in patient satisfaction existed between people whose neuropathic plantar diabetic foot ulcer treatment regimen included TCC, and those in whom FP was the offloading modality used.

Methods

Development of the offloading satisfaction questionnaire

Due to the lack of a suitable pre-existing tool, the authors developed a simple questionnaire – the Treatment Evaluation Survey (TES) – to investigate patient satisfaction with their offloading modality.

In consultation with five podiatrists with recognised expertise in the management of diabetic foot ulcers, aspects of TCC and FP with the potential to impact on patient satisfaction were identified. These formed an initial TES draft (eight questions scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale; two open-ended questions).

The draft was distributed to several people with expertise in questionnaire development and healthcare research to examine face and content validity. For further development of face validity, the draft was piloted with eight people with diabetic foot ulcers currently using offloading modalities, who were asked to provide feedback on the (i) English expression, (ii) time taken to complete the questionnaire and (iii) ease of use.

Feedback from the professional and patient groups was incorporated into the final TES version (nine questions scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale; two open-ended questions; Appendix I). The TES and a sheet that collected demographic and diabetes-related clinical information, including duration of the ulcers related to this study, were combined in a study package for distribution to participants.

Participants

Participants were recruited through high-risk podiatry clinics across Australia. Podiatrists from participating clinics introduced the study to their patient population and recruited volunteers who met the inclusion criteria, which were:

- A plantar neuropathic diabetic foot ulcer, the management of which included either (i) TCC or (ii) FP at the time of the survey period, and for a minimum of 4 weeks preceding it.

- Receiving standard wound care (local debridement, moist wound healing, adjunctive therapy as indicated).

- English fluency sufficient to complete a survey and give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were:

- Ischaemic ulcers and those with other conditions resulting in impaired blood flow (e.g. severe vasospastic disease, long-standing oedema, vasculitis).

- Acute Charcot neuroarthropathy.

- Osteomyelitis or soft tissue infection.

TES distribution, completion and return

Podiatrists from participating clinics gained informed consent form volunteers and distributed the study packages provided by the investigators. Questionnaires were self-administered by participants. Participants were asked to return the completed study packages directly to the investigators.

Ethics approval was granted by La Trobe University’s Faculty of Health Sciences Human Ethics Committee (FHEC03/051) and subsequent institutional ethics approvals were gained as required.

Data analysis

Responses to the nine TES select-a-response questions were tallied to provide a total score out of 36 (the total TES score [tTES]). Higher tTES scores indicate greater patient satisfaction with their offloading modality.

Data were analysed using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to compare group means for TCC and FP, and for the nine individual TES select-a-response questions. The two open-ended questions underwent thematic analysis.

Results

Sixty questionnaires were distributed and 28 returned (response rate, 46.7%). The cohort comprised 13 people (nine men; two women; two not specified) receiving TCC and 15 (11 men; three women; one not specified) receiving FP. Two TCC participants and one FP participant returned incomplete study packages; these were regarded as missing data for the purposes of analysis.

Mann–Whitney U-tests showed no statistically significant differences between the TCC and FP groups for age, diabetes duration or foot ulcer duration (all P>0.23; Table 1).

tTES score

The TCC group returned a greater range of tTES scores (range, 7–30) than the FP group (range, 21–36). The mean tTES score for the TCC group was 24.4±5.9, and was significantly lower than the mean FP group score (31.4±4.8; P<0.001). One FP participant failed to complete TES question eight, thus it was not possible to calculate a tTES score for that participant.

TES individual items

For the nine TES select-a-response questions, the FP group was significantly more satisfied with day-to-day activities (question 3; P=0.003), sporting, leisure and work activities (question 4; P=0.001), steadiness during walking (question 5; P=0.044) and lifestyle adjustment (question 8; P=0.005) in relation to their offloading device than the TCC group.

There was no significant difference between the groups for answers to questions 1, 2, 6 and 7, which assessed their current level of satisfaction with their offloading modality, whether wearing the offloading modality was unpleasant, the participant’s perception of whether the modality was working and how time-consuming they found their offloading clinic appointments.

TES open-ended questions

Answers to the two open-ended questions (question 10: What aspects of your foot pad/cast do you like and dislike? question 11: Has wearing your foot pad/cast changed the way you feel about yourself?) corresponded well to the content of the nine select-a-response questions. Responses to the open-ended questions centred on the themes of mobility, stability and healing.

TCC participants frequently described the negative impact of their offloading modality on mobility, stability, activities, of daily living, sport, leisure and work activities, and the high degree of lifestyle adjustment to accommodate their TCC. FP participants frequently reported how unpleasant they perceived their offloading treatment to be, commonly with reference to the malodour of the FP. TCC and FP groups both reported that they understood that their treatment was important to achieving healing of their foot ulcer, which was deemed to be a positive aspect of the offloading therapy.

Discussion

There are few data on the impact of offloading regimens on patient satisfaction in diabetic foot populations. Given that offloading is one of the cornerstones of gold-standard neuropathic foot ulcer treatment, the paucity of research on patient satisfaction with these modalities is a large gap in the literature.

The findings of this study imply that differences in treatment satisfaction exist between the two groups surveyed; the mean tTES score for the FP group was significantly higher than that of the TCC group, suggesting relatively higher overall levels of satisfaction among those receiving FP. However, the data reported here are not absolute, rather the relative satisfaction of people receiving the two offloading modalities is compared.

Expectably, the non-removable nature of TCC means that the modality is likely to have a greater impact on lifestyle than the less intrusive, removable or in-shoe offloading options. Thus, that TCC, relative to FP, had a more pronounced negative effect on patients’ overall satisfaction is not surprising.

Along with healing rates, mobility and activity impairment, and degree of lifestyle adjustment, associated with various offloading modalities should be explicitly discussed

with people requiring offloading. Patient choice in interventions that have such broad lifestyle implications is important; for some people, lifestyle issues will be of greater importance than speed of healing, and vice versa. In developing a comprehensive management plan for the person with neuropathic diabetic foot ulceration, it is strongly recommended that clinicians attempt to find balance between desired clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Limitations

Other investigations into quality-of-life issues among people with diabetes have achieved response rates between 65% and 81% (Anderson et al, 1997; Glasgow et al, 1997; Petterson et al, 1998; Ragnarson et al, 2000). In comparison with these studies, the response rate achieved in the present study (46.7%) was low and may not be representative of the wider population with diabetic foot ulcers using offloading modalities.

As this was a multicentre study, the authors were unable to control whether the study packages were distributed. Given the geographical spread of participants, no formal follow-up was possible. It is acknowledged that self-administered questionnaires tend to result in lower response rates when compared with other methods such as telephone or face-to-face interviews (Abramson and Abramson, 1999).

While ulcer duration was not significantly different between the two groups, data on ulcer area and grade and the number of concurrent ulcers, and whether the active ulcer during the study period was a first episode of ulceration or a recurrent ulcer, were not collected. It is possible that the TCC group had a higher disease burden than the FP group, resulting in overall less satisfaction in their treatment being reflected in the questionnaire.

The TES demonstrated good face validity, but it is acknowledged that the survey’s validity was not exhaustively examined prior to use. The results should be interpreted accordingly. Further validation should be undertaken before use of the TES in a larger study.

Conclusions

The results of this pilot study indicate that participants using FP in the management of neuropathic foot ulcer reported higher levels of overall satisfaction than participants using TCC. Key issues were the impact of the offloading modality on the activities of daily life, sport, leisure and work activities, stability and the degree to which the participant had to adjust their lifestyle to accommodate their treatment. These factors are largely associated with mobility, which is limited by offloading, but especially so by TCC.

These results suggest that, for some people, the impact of specific offloading on functional capacity, should be considered alongside anticipated healing rates when individualising offloading strategies. Further research into this important issue is warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the staff, patients and managers of the high-risk podiatry clinics around Australia who were involved in this research.