Technological advances and improvements in local treatments for diabetic foot disease place clinicians under ever increasing pressure to preserve the foot (Watkins PJ, 2003; Smith J, 2003). Often a successful outcome is followed by a rapid recurrence necessitating further hospitalisation. Clinicians should always consider whether the best interests of the patient might be served by primary amputation. The aim of any treatment is to deliver a fully mobile patient back into the community. It is not possible to say which patient in the photograph has had a below-knee amputation (BKA), and which has had successful local surgery in the foot (Figure 1).

When should we do primary amputation?

The advantages and disadvantages of primary treatment by minor and major amputations are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Amputation rates

Between 1988 and 2002, 3535 vascular operations were performed in 2591 patients by one surgeon at the Royal Bournemouth Hospital. A total of 2412 of these operations were in patients without diabetes, whilst 649 (27%) of them were in patients with diabetes. There were 328 primary amputations (60%) in patients with diabetes from a total of 550 amputations in the series.

Of these, there were 282 toe amputations, 110 BKAs and 39 above-knee amputations (AKA; table 1). AKA was uncommon in patients with diabetes (18%).

Of the 389 patients who had toe amputations, 44 (19%) required revision of their toe amputation to either the below knee or above knee position. Figure 4 shows the individual 44 patients and the time in days between their original operation and the revision. Thirty-one (70%) of these patients required revision within 6 months of the original operation. Of these patients, 25 patients needed two operations, 17 required three operations and two required four operations. Patients, required a mean of 2.46 operations per amputation episode.

Of the 240 patients, 196 had toe amputation alone, 193 patients had either primary BKA or revision of toe to that level. Therefore, approximately 50% of the patients in Bournemouth ended up with a BKA; a very high proportion.

Indications for primary BKA

It is difficult to know whether to treat the patient in Figure 5 by local measures or by primary major amputation. Possible indications for primary BKA instead of local amputation in the foot are: previous extensive hospitalisation, limited life expectancy, patient choice, age, state of circulation, effect of a failed distal bypass, and failed conservative management.

Previous extensive hospitalisation/intervention

When a patient has already spent a long time in hospital having local treatment to a diabetic foot, major amputation with rapid return to home and mobility with an artificial leg is often preferable in the presence of a doubtful outcome from local treatment.

Limited life expectancy

Treatment of the diabetic foot is very time consuming, often requiring a prolonged hospital stay. For a patient with a limited life expectancy a short admission for major amputation may mean more time at home. Three months of the 5 remaining years of life is 5% while 3 months in 1 year is 25%. We should aim to minimise the time spent in hospital as these patients are often towards the end of their lives.

Patient choice

Patients should always be offered three choices: no treatment; continued conservative management involving minor amputation (provided that there is reasonable circulation); or major amputation. Surprisingly, patients often choose the major amputation route.

Age

Younger people adapt very well to BKA, but because they are likely to have better circulation they are more likely to heal local amputations in the foot. However, young people are young enough to return with further problems.

Elderly people are less likely to adapt well to major amputation, but are also less likely to have good circulation and the ability to heal locally within the foot.

State of circulation

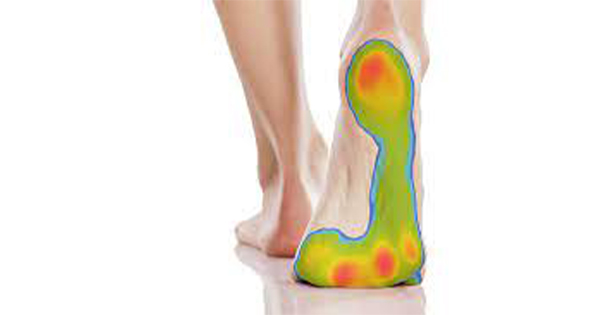

For local amputation in the foot to heal, the circulation must be adequate. In practice, this means at least one patent artery to ankle level.

A combination of pulse palpation with ankle brachial pressure index measurement may provide sufficient information, but angiography followed by angioplasty or bypass may be necessary to ensure adequate circulation.

The effect of a failed distal bypass

Incisions on the medial or lateral side of the calf for bypass surgery can reduce the chances of successful healing of a BKA. So paradoxically, patients who have had a bypass which fails may require more proximal amputation than if no bypass had been attempted.

Failed conservative treatment

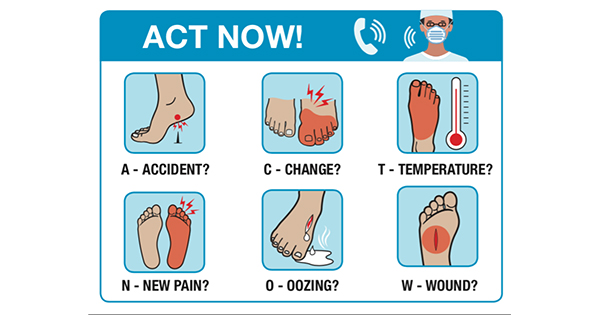

Some patients may have been treated for months in hospital clinics without success. Figure 6 shows a patient who has a neuropathic foot. Even if healing is eventually achieved, there is a very high risk of new ulceration despite very careful attention to footwear.

Algorithm for management of patients

38% of patients have a foot which is not salvageable and these patients should have a major amputation from the outset. If the circulation is normal, the foot is salvageable, and the patient is young, then local amputation is an option. However, 19% will fail their local amputation and require major amputation.

Some patients with reduced circulation, particularly the young, should be investigated with a view to vascular reconstruction. If this is straightforward, subsequent local amputation should be tried. If not, major amputation should be offered early.

An algorithm for the management of patients is shown in Figure 7.

Conclusions

Major amputation should be considered as an option for every patient with diabetic foot disease. The decision will be influenced by factors such as: age of the patient; mobility of the patient; whether the patient has a job and what it is; what the family situation is; what the life expectancy is; what previous treatment they have had; patient choice; the morphology of the foot and the circulation to the foot. It is important to remember that 50% of patients will end up with a major amputation.

Major amputation should not be regarded as failure. A well-healed skew flap BKA provides an excellent long-lasting outcome for the patient with diabetes who will achieve near normal mobility with very little need for further hospitalisation (Figure 8).