Foot disease in patients living with diabetes has been shown to cost the NHS considerably, with approximately 1% of the budget being spent on active foot disease (Kerr et al, 2019). Eighty-per-cent of these foot problems are largely preventable, which is not only economically unviable but unsustainable whilst being an unacceptable burden to patients and the healthcare professionals (HCP) that support them. Early intervention through timely access and patient activation is key to reduce this clinical and economic burden. Evidence from research trials (Smith-Strom et al, 2017; Manu et al, 2018) and from NDFA data (NHS Digital, 2019) demonstrates that diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) severity, time to healing, risk of hospital admission and amputation are related to timely intervention by a HCP with the appropriate skills to deal with the problem.

Anecdotally, patients living with diabetes who encounter a ‘foot attack’ or acute diabetic foot problem often access help late, generally living with the problem before seeking help from a HCP, which is usually their GP. The GP at this point may refer directly to the Foot Protection Team (FPT) (Local Podiatry Service) or may refer to their Practice Nurse colleagues. Both of which may cause further delays to appropriate management from a HCP with the most appropriate skills to deal with foot problem, particularly if the patient requires review by the multidisciplinary foot team (MDFT). Often barriers are created within the healthcare system with complex patient pathways, poor knowledge of referral processes or services that are not necessarily user-friendly (Pankhurst and Edmonds, 2018).

HCPs themselves can be a barrier if they have a lack of awareness of the knowledge and skills required in management of the at-risk foot and feel that they can deal with the perceived ‘simple’ or ‘superficial’ DFU, particularly if they delay referral on to the HCP who has the most appropriate skills to deal with them. Consideration must also be given to the role the patient plays in accessing care at times of crisis. In respect of not recognising the gravity of their foot problem or, as often is the case of patients with peripheral neuropathy, not recognising the problem in the first place. The pressures of living with a chronic health condition and the numerous associated medical appointments can also be extremely challenging for patients in the working population. Apathy is sometimes demonstrated by others, with some patients feeling powerless to prevent ulcer occurrence or reoccurrence (Ashmore et al, 2018).

Patient activation describes the knowledge, skills and confidence a person has in managing their own health and healthcare (Hibbard and Gilburt, 2014). Patients with low levels of activation are less likely to seek help when they need it, follow advice and manage their health when they are no longer being treated (Hibbard and Gilburt, 2014). Conversely, patients with high levels of activation are more likely to engage in positive health behaviours and manage their health more effectively (Rix and Marrin, 2015). Identifying and removing the barriers to timely access of interventions combined with increasing patient activation is essential to improving clinical outcomes, improving the quality of care and patient experience.

Diabetic walk-in clinic

In Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (CAV UHB) diabetic foot services are managed by the FPS. Historically, patients with DFUs were either referred by a HCP or self-referred to the department. The referrals were then triaged as urgent and patients were offered appointments in ‘rapid access’ clinics within the CAV UHB locality. Like many NHS services these urgent appointments were often booked up quickly, reducing the capacity to provide timely access for all referrals. Within these clinics there was some wastage, with some patients failing to attend their appointment or patients on face-to-face review presenting with a non-urgent problem. To reduce harm, waste and variation, improve access to those patients who need care the most and increase patient activation in their foot health, the diabetic walk-in clinic (WIC) concept was developed.

The WIC enables patients to gain access to a HCP with the most suitable skills to manage their foot problem at times of crisis without the need of a referral from another HCP. It provides care closer to home without the need to attend acute hospital sites, affirming the prudent principles of healthcare in Wales. By receiving care from an expert HCP, a member of the integrated MDFT when intervention is needed, timely, effective care can be provided. This model of care provides a seamless service between primary, community and secondary care services with all HCPs signposting patients to WIC.

This new model of care also dovetails directly with an earlier project, ‘STANCE’, which invites all patients living with diabetes (without DFUs) newly referred to the podiatry service to attend a structured diabetic foot education session. Patients who are identified at moderate or high risk for DFUs are encouraged and empowered to manage their own foot health with confidence that if they need support it will be available and accessible for them (Jones and Goulding, 2018).

Aims

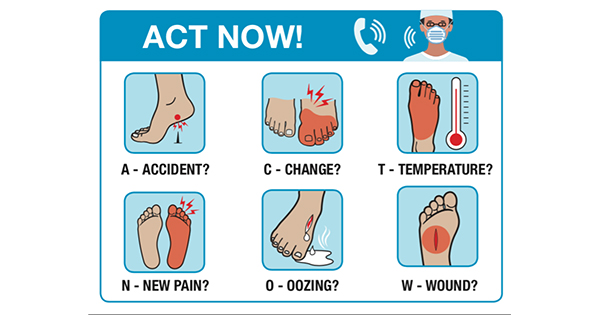

The primary aim of the project was to reduce the number of patients waiting longer than 3 days for their first expert assessment (attendance to WIC) by 20% within the NDFA audit cycle. A secondary objective was to implement and support an All Wales infographic designed for use by local university health boards to promote the need to access services in a timely manner at the point of crisis. Targeted at both patients and HCPs, it was anticipated that it would speed up appropriate access to the service. Timing of the project was pertinent as it enabled participation in the NDFA quality improvement collaborative 2018–2020.

Methods

By making changes to the appointment system, the WIC pilot project could be trialled without the requirements of additional resources and without causing undue additional pressures on the podiatry service. The project followed a Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model of improvement to ensure feedback from all stakeholders could be reviewed and incorporated as necessary; in addition the processes could be refined to optimise the service (NHS Improvement, 2018). The project also incorporated change management methodology, principally Kotter’s eight-step change model to ensure stakeholder engagement, manage the obstacles to change and enable sustained change (Mindtools.com, 2020).

WIC was initially piloted twice a week on a Tuesday and Friday within the podiatry department’s clinical hub. As the demand for this facility was largely unknown, the pilot was commenced, inviting patients from one locality of Cardiff, a cluster of 10 GP practices, to attend from December 7, 2018 for 8 weeks. This was advertised within GP surgeries using a flier on their TV screens, through sharing on social media and a mailshot to the HCPs in these localities. A newly devised All Wales patient infographic was also shared (Figure 1) to support the project. The project was also promoted directly within our existing caseload of patients receiving podiatric care.

The data for the project were primarily collected using the NDFA data collection tool. Additional data were also captured manually through a case note review process. Internal processes within the FPS were streamlined including using a skill mix within the clinical sessions, with a podiatry clinical assistant triaging patients, collecting baseline information and providing simple re-dressings after full assessments and treatment planning by the podiatrist. The feasibility of the project was determined during the initial pilot phase which led to the opening of WIC to all GP practices within the Cardiff and Vale boundary in February 2019.

Results

During November 2018 and November 2019, 313 patients attended WIC, of these 45% of patients presented with a new DFU and 38% presented with a ‘diabetic foot attack’ defined as new onset of ‘redness, heat, pain or swelling’ (Table 1).

Access to HCPs with the appropriate skills to manage the complexity of this patient cohort was improved, with significantly more patients self-presenting after the commencement of WIC (Figure 2). The numbers of patients waiting longer than 3 days reduced from 55.36% to 35.45%.

In addition, positive improvements to the clinical outcomes of the patients were demonstrated. NDFA data shows that the number of patients with persistent ulcerations has reduced, the numbers of patients alive and ulcer-free has increased and the number of patients with less severe DFUs has increased (Figure 3).

Discussion

Evidence has demonstrated that patients with DFUs who present early to an expert HCP have better outcomes so time to first expert assessment is crucial. The improvements in NDFA data during the time period since the commencement of WIC were encouraging. With more patients self-presenting, this indicates that more patients were attending the FPS rather than other HCPs to seek help, thus reducing the need for multiple clinical appointments with different HCPs. Furthermore, by having a member of the MDFT providing the initial assessment, this has supported and prevented unnecessary waste of NHS resources, particularly unnecessary appointments with other members of the MDFT.

Increased numbers of self-presenting patients is also suggestive of increasing patient activation, although without measuring patient activation it is difficult to draw this conclusion. It does, however, indicate this type of service provision supports timely access for patients. Increases in the numbers of less severe DFUs during this time period may also suggest patients accessing care much earlier. In addition, improvement in healing rates could also suggest that patients are seeking access to care at the point of crisis. However, in the absence of data that examines duration of DFUs, this conclusion cannot be drawn. It is widely acknowledged that NDFA data in its entirety does not provide a true and accurate reflection of the clinical outcomes of a diabetic foot service.

In Wales, the requirement for patient consent to NDFA participation can affect recruitment rates, as can recruiting those patients who present with more severe ulceration that requires hospital admission initially. Examination using a case note review process of these patients who present late to HCPs could improve understanding of the continuing barriers to appropriate care. Despite these shortcomings, the initial results since commencement of WIC have been positive.

There were some concerns of implementing this new service provision. In part due to the unknown numbers of patients that may attend one of the sessions. This was safely accomplished by ensuring that appropriate care was given and patient expectations managed by utilising skill mix within the team and multiple clinical treatment rooms. Ensuring the availability of competent and capable HCPs to cover the clinic has meant access to the clinic has been maintained since its introduction. There were also some concerns that patients would perhaps ‘misuse’ this service and use it as a way of gaining quicker access for routine podiatry or musculoskeletal interventions. As shown in Table 1 this has only been the case in a small number of cases, with 83% of patients presenting with a foot pathology requiring urgent intervention. Those who presented with a non-urgent foot pathology were well managed by the podiatry team, who sought the opportunities to engage, educate and empower the patients without providing any clinical intervention.

The impact to patients cannot be underestimated. Ensuring appropriate, effective care is available closer to home has meant that many patients have not required hospital admission. Their ‘foot attacks’ have been managed within the community, utilising an MDFT approach, which has prevented unnecessary burden to the acute hospital sites but facilitates a patient centred approach. This has also supported a ‘step-down’ approach within the FPS, which enables appropriate use of resources and skill mix, which underpins the prudent principles of healthcare demonstrated in Wales.

Future developments

Within CAV UHB successional planning has been a key objective to support the All Wales DFU pathway (Figure 4) and sustainability of diabetic foot services. Ensuring podiatrists have the appropriate skills and experience to provide this high level of care supports the viability of this model of care. WIC has been embedded into the UHB diabetes healthcare pathways for primary care, ensuring early access at times of crisis for our patients. Patient collaboration is key and the patient representative in the UHB diabetes service improvement group has been crucial to support its adoption. To support further improvements, it is planned to increase the number of WIC operated during the working week. The introduction of Patient Group Directives (PGDs) will facilitate a ‘one-stop shop’, increasing clinical and cost efficiencies in addition to patient experience. Further work is planned to engage patients from ‘hard to reach’ groups, such as Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) through a local organisation, The Mentor Ring, to ensure there is equity of access for patients from any social background. Further evaluation of patient experience of WIC is planned, as is the evaluation of future models of providing a ‘one-stop shop’ for our patients.

The results of this project support the direction of travel in Wales, where patient activation is essential to reduce the growing economic burden of diabetes on the NHS. Understanding how HCPs can support and influence patient activation is vital. David Hughes MBE Clinical Lead and Manager of Podiatry, Orthotic, MCAS and Persistent Pain Services, Swansea Bay UHB, has been leading on this with the All Wales Diabetic Foot Network (AWDFN). He is currently delivering training on the concept of patient activation to each podiatry service in Wales. Funding has been secured to enable the use of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM®; NHS England, 2020), which will support the development and implementation of a prudent model for the prevention of diabetic foot-related crisis across Wales.

WIC and COVID-19

Like all NHS organisations across the UK, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic presented uncertain and challenging times. Welsh government outlined that emergency podiatry services and limb at-risk monitoring were included in the essential services that should remain available across NHS Wales during the outbreak (Welsh Government, 2020). WIC continued and although there was a drop in attendance compared to last year (Figure 5), patients have still continued to attend.

During this time, it has been as important as ever to ensure that patients have access to HCPs with the most appropriate skills to manage their foot crisis. With limited access to our MDFT colleagues, face-to-face clinical appointments cancelled and surgical procedures put on hold, new ways of working have developed. The use of virtual MDFT clinics, telephone and video consultations has enabled the podiatrists to continue to manage this complex patient cohort. Changes to the way we have operated WIC has also been required. Due to requirements for social distancing, it is no longer acceptable for patients to ‘turn up’ for a sit-and-wait clinical model. However, at the heart of this model, patients require access at point of crisis. The use of a ‘phone first’ system allows patients to gain access to a HCP who can triage appropriately using telephone or video consultations to provide advice and arrange a face-to-face appointment within 24 hours.

Conclusion

The initial findings of this project suggest that WIC has improved access to patients with a diabetic ‘foot attack’ within CAV UHB. For many patients, their major concerns are accessing services when needed, WIC supports their engagement and facilitates access to care when required. It is well documented that activated patients use less resources and have better clinical outcomes (Rix and Marrin, 2015). Further work to embed patient activation within diabetic foot services is required to support patients and HCPs to improve clinical outcomes, quality of care and patient care.