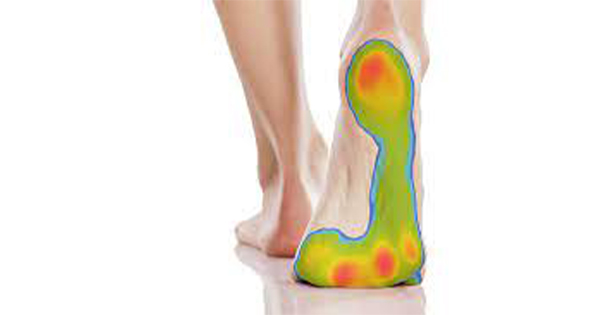

Therapeutic footwear adherence is an essential part of the diabetic foot ulcer prevention strategy (Cavanagh, 2007). Its role is to reduce elevated pressure under the foot and to protect the foot from trauma (Paton et al, 2011). However, to be effective footwear must be worn during weight-bearing activities.

Several authors have reported that many patients are ignoring the footwear recommendation for continuous wear, but it is not clear why (Knowles and Boulton, 1996; Macfarlane and Jensen, 2003; Waaijman et al, 2013).

This case study forms part of a research study (Paton et al, 2014) exploring the understanding and experiences of people at risk of diabetic foot ulceration who have been prescribed with therapeutic shoes. It aims to provide a unique insight into the personal experience of a working female. Work by Williams et al (2010) acknowledges the particular challenge female patients face when provided with therapeutic footwear.

Case study

A 59-year-old woman with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy was interviewed about what it is like to wear therapeutic footwear. Her name has been changed to protect her identity.

Barbara lives with her husband and is currently in full time employment in an urban office environment. She suffered bilateral Charcot arthropathy 10 years ago. The subsequent midfoot deformities were the trigger for the therapeutic footwear referral (Figure 1).

The interview data was analysed using an interpretative phenomenological approach. This methodology has been described in detail by Richie and Spencer (1994). One overarching theme emerged from the interview data – transition of adjustment toward accepting therapeutic footwear. Three other themes were then organised in terms of this concept:

- Integrating therapeutic footwear within self-image.

- Maintaining a sense of independence/control of self within everyday life.

- Adjustment of emotional state toward footwear (Figure 2).

Results and discussion

Transition of adjustment toward accepting therapeutic footwear

Throughout her interview Barbara recounted a journey over time, describing how her thoughts and feelings towards the footwear eventually changed from absolute rejection toward complete acceptance. Interestingly, Walker et al (2004) report a similar ongoing adjustment within the wider context of diabetes.

“Time changes. Probably if I was asked again now what’s different now, I don’t know. I’m a bit older, more used to it.’”

There are a number of key events that Barbara considered instrumental to her acceptance of therapeutic footwear; points in time when a conscious change in mindset toward therapeutic footwear acceptance occurred. In this first example Barbara recognised the functional benefit of therapeutic footwear, and for the first time considered function to be more important than aesthetics.

“I thought right, [pause] this is … where I am now and this is what I’m going to be wearing for the rest of my life. I thought, well yeah, what’s the big deal? In a way I’m still walking and I can still get out and about.”

In the second example Barbara described the moment when she felt ready to make the difficult decision to commit to wearing her therapeutic footwear (Figure 3).

“I did have a lot of shoes at one stage. I liked Russell & Bromley, Stewart Weitzman, Bally, all of those. They were really lovely shoes. It did break my heart. I kept them because I thought ‘one day, one day’. But then you look at your feet and you think there’s just no way … I’m never ever going to be able to wear this. I parcelled them all up, cause they were all in boxes … I took them down to [the charity shops] and … thought right, that’s the end of it.”

This description of events gives insight into Barbara’s emotional attachment to footwear. The boxed storage suggests her footwear collection was cherished. Choosing to retain her retail footwear preserved the link to her past self, highlighted the enormity of learning to accept her foot pathology and implied an initial denial of the permanence of her foot condition. The eventual act of giving away her collection of designer shoes was symbolic of accepting the condition and moving on, signifying a change in how she viewed herself. The words “right that’s the end of it” indicated an end to a difficult chapter in her life and a readiness for a fresh start as a new self.

The three themes follow the concept of a temporal journey from rejection to acceptance, demonstrated by the oppositional relationship of the representative quotes.

1. Adjustment of emotional state towards footwear

Barbara recounted the shock and distress she endured when first provided with her footwear.

“I tell you, they looked like diving boots … I was given them, put them on and told to go away and wear them, and I went out in the car park and cried, because I just thought this … cannot be right.”

Likened to diving boots, Barbara conjured a picture of something big, heavy, and unfeminine. This clear recollection of how upset she felt at the prospect of wearing the issued footwear conveyed the traumatic psychological impact of this initial experience. In sharp contrast is the description of her current footwear use, which is one of utter reliance.

“I’m petrified of standing on something that’s going to damage the bottom of my foot or cause a cut or infection or something in the foot so I would never ever go anywhere without either … the slippers or the shoes. You know, not even if the house caught fire. I’d sit, put my slippers on ’cos …I’d have to run outside, so I would still put them on.”

The now deep-seated nature of her current footwear compliance is clear, demonstrated by her suggestion that the fear of being trapped by fire is outweighed by the risk of walking without the protection of her therapeutic footwear.

2. Integration of therapeutic footwear within self-image

Barbara initially remembered the repercussions of being given what she viewed as unacceptable footwear.

“I just couldn’t believe that I was just given these shoes … and I thought … I want to work, I want to be relatively normal and do the things that I want to do. I just thought I can’t do that with these horrible shoes.”

Barbara continued throughout her interview to describe the negative first impression of her therapeutic footwear. Her initial focus on aesthetics reflected her opinion of footwear as a fashion item, not a medical device. She was concerned that wearing such footwear would lead to social exclusion. Footwear style represented a powerful symbol of social normality. Having changed her view, Barbara then responded to adjust her self-image to compensate for having to wear orthopaedic footwear.

“I would get ready for work and then I would choose the colour of shoes I was going to wear. If I wore blue trousers, I’d wear navy shoes, or black I’d wear the black shoes … If you like to match the outfit and you felt [pause] like properly dressed, if you like – you don’t feel too conspicuous.”

Barbara was asked what she meant by conspicuous (Figure 4).

“I’m aware that my feet are an odd shape. I suppose I’m very conscious of that. That’s probably why I wear … trousers quite a lot, but I do have long skirts, I suppose to hide the fact. People notice that, they look at you, they like scan you down, don’t they? Some people will comment ‘What’s wrong with your feet?’”

Barbara dedicated much time and effort to ensuring her therapeutic footwear and feet were not the focus of her appearance, to create an impression and feeling of normality. Similar concealment strategies have been observed by Kaiser et al (1985) in those with a physical disability.

3. Maintaining a sense of independence and control of self within everyday life

Barbara found the loss of control over her footwear choice difficult to come to terms with.

“Because you could go into any shop you like and spend whatever you wanted on a pair of shoes, whether it be 50 quid or 500 or whatever, and that was going to stop, it did stop. Because there was somebody then saying to me: ‘No, you can’t have that, you can only have this’.”

Previously Barbara enjoyed shopping for expensive, stylish shoes; she liked the sense of control and increased choice her spending power afforded her. In Barbara’s account, the change in tense “that was going to stop, it did stop” reflected the time it took for her to accept her new situation. The re-establishment of control and choice was an important part of Barbara’s journey to therapeutic footwear acceptance. She described a transition from victim of injustice to advocate.

“I just thought he [the clinician] wasn’t going to do it to me. I thought there must be something better … than what I had … I said to him, ‘They’re not doing it to me. I will fight and I will find somewhere [more acceptable].’”

“They’re doing it to me” implied the existence of a hierarchical relationship between herself and the clinician. The repetition of the phase “I will” conveyed the importance the situation and her determination to succeed. The use of the word “fight” suggested conflict and a readiness to battle for control. Finally, Barbara regained control through self-imposed empowerment. Having established a more collaborative role with her footwear provider she became satisfied with the restricted choice.

Patient/practitioner collaboration as a route to empowerment is described and supported by Marrero et al (2013) as a means to improve adherence.

Barbara attributed her fear of lost independence as her motivation for compliance.

“I wouldn’t be able to function properly, go to work or whatever, because normally if there’s damage to my feet in any way it’s rest and elevation … hospital visits as well and I just don’t do sitting around doing nothing very easy. It would stop me swimming, it would stop me walking … stop you functioning really. So [pause] to me to do something so simple, to put on a pair of shoes instead of just going … oh, shall I chance it.”

Barbara’s motivation for compliance came from a fear of being immobilised, more specifically a fear of forced withdrawal from work and work life. Her mention of “do something simple” indicates how much has changed for Barbara over time. Footwear adherence is now considered almost effortless.

Summary and conclusion

Barbara’s journey illustrates the psychosocial issues associated with wearing therapeutic footwear. This concept of a temporal journey from rejection to acceptance shows the complexity of issues associated with this strategy to reduce foot ulceration in people with diabetes.

Barbara recounted a number of key moments and events over time that were important in changing her perception of therapeutic footwear. Establishing a more collaborative role with her footwear provider gave an increased sense of choice regarding some aspects of her footwear design (colour, style).

This change in approach induced in Barbara a sense of satisfaction and acceptance of this limited choice. She is now able to comply with the recommendation to always wear her therapeutic footwear. Barbara was compelled to change her behaviour for fear that foot ulceration would force long-term confinement.

The re-establishment of self-image and sense of personal control was paramount to therapeutic footwear acceptance, initially outweighing fears about the risk of ulceration.

In brief this more collaborative approach with her footwear provider was achieved through a number of measures that together changed Barbara’s position in the patient/provider relationship to one of perceived control and empowerment. This included incorporating process measures encouraging patient engagement, such as providing Barbara with a contact number and named person to phone during normal working hours to discuss footwear concerns and maximising choice of aesthetic footwear features such as colour and style.

More powerfully, however, investing time to build a relationship of trust and understanding between patient and practitioner in which Barbara believed her thoughts and feelings were heard and considered proved key to achieving a true feeling of collaboration.

Clinicians should be sensitive to the psychological impact of therapeutic footwear provision and understand that patient perceptions about footwear can change with time and personal experience.

Footwear education for people with diabetes should therefore be ongoing and be flexible enough to consider an individual’s current thoughts and feelings.

Further research is needed to determine if this approach could improve adherence to strategies to reduce foot ulceration.

Funding declaration

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.