Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are complex chronic wounds, which have major long-term impacts on the morbidity, mortality and quality of the patient’s life. The incidence of DFUs have been reported to have a one-in-four risk during an individual’s lifetime, with 5–7% prevalence (Miller et al, 2014; Bader, 2008) and up to 44% mortality at 5 years in those who have undergone an amputation (Lipsky, 2004; Kerr, 2017). The National Diabetes Audit report on complications and mortality (Kerr, 2017) suggests that the numbers of minor amputations (to midfoot) have risen since 2010, and people with diabetes are around 23-times more likely to have a toe, foot or limb amputated than those without diabetes (Kerr, 2017). Foot problems in people with diabetes also have a significant financial impact on the NHS, accruing costs at secondary, community and primary care levels, increasing outpatient costs, bed occupancy and prolonged stays in hospital.

It is estimated that £14bn is spent every year on treating diabetes and its complications, and that the cost of diabetes to the NHS is over £1.5m an hour or 10% of the NHS budget for England and Wales (Diabetes UK, 2019). Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) from 2014/15 showed that 89,055 diabetic admissions were for foot ulceration, representing 1 in 33 patients with diabetes (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015; Kerr et al, 2019). The mean length of stay for ulceration was estimated to be 16.58 days (compared with 7.46 days in those patients with diabetes admitted without foot ulceration), thereby representing an 8.04 day increase in length of bed stay, with a significant cost to the NHS (Kerr et al, 2019). The estimated cost of these extended hospital admissions is suggested to be in the region of £145.45mn (Kerr et al, 2019). The projected increase in people living with diabetes by 2030 will see these costs increase significantly, when the number of people affected by diabetes is expected to reach 5.5mn in the UK (Diabetes UK, 2019).

A diabetic foot infection is defined as a soft tissue or bone infection, occurring below the malleoli, and is the most common complication of diabetes requiring admission to hospital; additionally, it is the most common cause of non-traumatic lower-limb amputation (NICE, 2002), with DFUs preceding more than 80% of amputations in people with diabetes (NICE, 2002). Many patients present to the podiatry clinic, who then act as ‘gatekeepers’ (Blanchette et al, 2020), and there is very little literature on patients presenting to the podiatry clinics and then being assessed by this speciality to determine the need for hospital inpatient admission.

The podiatry service at University Hospitals Birmingham (UHB) is a small team (3.3WTE substantive staff members with the additional three Trust sites being staffed by a local podiatry department on a service-level agreement). The highly skilled clinical podiatrists provide treatment for both outpatients and inpatients within the Trust, 5 days a week and are supported by weekly multidisciplinary team ward rounds and Diabetic Foot Clinics.

The skill mix and specialist interests of the clinical staff underpin the holistic management of the diabetes-related foot problems referred to UHB.

Methods

A pragmatic prospective audit was conducted from August 1, 2017 to August 31, 2019 at UHB NHS Foundation Trust, to include all patients referred directly for inpatient admission into the acute hospital (via the Acute Medical Unit and Accident and Emergency Department) from a secondary care outpatient podiatry-led clinic. These were patients who were deemed by the podiatrist to need urgent admission to hospital. All patients were recorded for admission date and date of discharge (length of bed stay), with outcome data for the primary reason for admission along with hospital treatment and the ongoing outcome. Clinical data, including date and cause of death, was extracted from hospital electronic notes.

Results

During the study period, 58 patients (68 acute admissions; 48 males) were referred from clinic to acute medical or surgical teams. Of these, eight patients were admitted twice and two patients had three admissions. The mean age of the patients was 53 years (range 40–90 years), with most patients aged between 50–69 years old (70.6%). Most patients were white British (36 males, 9 females), whilst the remainder were either of Indian, Pakistani, African or Caribbean origin. Fifty-two (89.7%) patients lived with type 2 diabetes and 10 patients were dialysis-dependent.

The most common reasons for referral and admission are summarised in Table 1. 32 patients (47%) were admitted at a podiatry appointment after a routine redressing/walk-in, 11 (16%) were seen as urgent/emergency walk-ins, 8 (11.8%) following attendance at the multidisciplinary diabetic foot clinic requested by podiatry, 10 (14.7%) following referral from primary care (general practitioner (GP)/district nurse/practice nurse/community podiatry) and seven (10.3%) from other hospital speciality referrals (such as vascular surgery or renal medicine).

The intervention of these patients after admission is summarised in Table 2. The mean length of stay was 15.8 days (1–90 days), with females staying for a mean of 22.7 days (1–90 days) and males 13.8 days (1–50 days). Eleven (19%) patients died during the audit period, including two during their actual hospital admission. Causes of death included cardiovascular (five patients), cancer (two patients), cardio-renal syndrome (one patient) and pneumonia (one patient) – the cause of death was not known in two patients. Of the patients who died, 88.9% died within 1 year of this admission to hospital.

Discussion

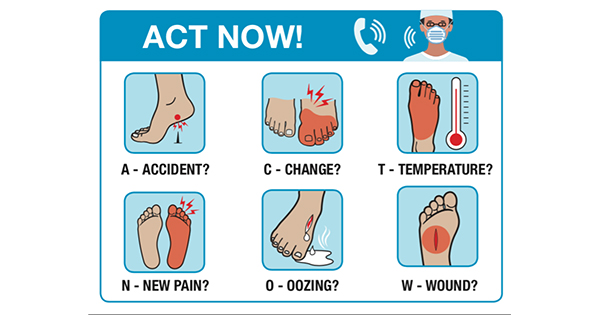

This prospective audit has shown the importance of robust care pathways in ensuring that patients have access to the right medical interventions at the optimum time. Many hospitals now have access to a multidisciplinary Diabetes Foot Clinic at least once a week, similar to our practice. With patients presenting directly to daily podiatry-led clinics at all other times, this exposure and autonomous practice enables podiatrists to act as ‘gatekeepers’ and determine which patients need admitting, from those that can be managed on an outpatient basis (Diabetes UK, 2019). Early referral to specialist care pathways can both reduce healing times and the need for lower limb amputations by reducing ulcer duration (Kerr et al, 2019), while the National Diabetes Foot Audit (NDFA) has unsurprisingly found that delays in foot assessment are linked with both an increased ulcer severity and duration. The individual clinical skill and judgement regarding the need for hospital admission is difficult to quantify, and is often the result of good clinical knowledge and experience from working within specialist clinics and the multidisciplinary team, with particular reference to the red flag markers:

- The acutely red/hot/swollen foot

- Spreading cellulitis or tracking

- Allied with systemic symptoms indicative of sepsis

- Critical limb ischaemia

- Purulent gangrene, or

- Increasing rest pain with absent pulses.

Our results show that the majority of patients admitted have severe soft tissue infection, requiring intravenous antimicrobials. This is especially important to recognise, as many of these were already receiving oral antimicrobials. However, there were also a large number of patients who eventually required minor amputations and vascular interventions, with many of these patients (47%) not seeming to appreciate that they were unwell, because they attended for routine podiatry appointments as scheduled.

There is very little data regarding the positive effect of podiatrists on major or minor amputation risk in patients with diabetes (NICE, 2002), so additional research is suggested, with a systematic review determining the impact of podiatry in the multidisciplinary foot team (MDFT) being indicated (Blanchette et al, 2020), and further assertions being made that there is little research to support the impact that amputation has on a person’s quality of life (Levy et al, 2017). The expertise and skills of podiatrists in the MDFT have been shown to improve patient outcomes and limb salvage (Sanders et al, 2010; Buckley et al, 2013).

Audit data will continue to be collected contemporaneously, in order to inform a service redesign, specifically around improving the early access to podiatry services (both in secondary and primary care), and timely provision of appropriate antimicrobials, which will support the assertion that early referral to specialist care improves patient outcomes, reduces length of bed stay and reduces healing time. Although this audit involved a relatively small cohort of patients, it has demonstrated that patients with diabetic foot problems have multiple comorbidities that need to be addressed for optimum outcomes, as not all complications are foot-related and occur across all age groups. As frontline care providers, podiatrists should be able to identify and escalate patients who need urgent hospital admissions, rather than waiting for the next medical appointment, as ‘delays lead to dire results’.