The first part of the National Service Framework (NSF) for diabetes, the Standards document, was published in December 2001 (Department of Health [DoH], 2001) and, after a lengthy holding of breath, the Delivery Strategy was published late the following year (DoH, 2002). The thing that was most noticeable about this NSF compared to the previous coronary heart disease one was the distinct lack of resources (money) to accompany it. For that, we in primary care had to wait for the new General Medical Services (nGMS) contract (British Medical Association, 2003), where approximately one-third of practice funding comes from the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QoF). So, are they compatible from a practice nurse’s viewpoint?

Compatibility in practice

First of all consider the standards in the NSF (see Table 1). Standard 1 is a laudable aim, but where does it fit into the nGMS contract? Nowhere I can find. Under nGMS Essential Services, management of chronic disease may be included but not prevention thereof. It is not in nGMS Additional Services or Enhanced Services so you would think it must be in the QoF, where practices get paid on collection of points (indicators) for achieving agreed targets. There are 18 clinical indicators but all are for diagnosed diabetes.

NSF Standard 2 is identification of diabetes. The recommendations of the House of Commons obesity report (2004) contained 69 recommendations for consideration to prevent obesity, yet it is not a high priority in preventing diabetes. In fact, nGMS only awards three points out of 99 for measuring body mass index in those already diagnosed. It would be good to have more time in practice to address this concern but it has not been given a high enough profile in the nGMS contract to allow nurses to argue their case.

The Delivery Strategy goes further on empowerment (Standard 3, Table 1) than the nGMS contract. It outlines a partnership between the patient, health professionals and social care. As Meetoo and Gopaul (2005) point out, it is not possible to empower someone if they do not want to be empowered, however they must take responsibility for their own actions. Participation in self-care does lead to a reduction in complications and we should do our utmost to get that across. I do believe we should be empowering people through the commitment in the NHS Plan (DoH, 2000) for patients to receive copies of clinical correspondence and in the NSF for patients to hold their own information (Table 2). Hand-held records are no new thing; they have been used in maternity care for a long time. Is it our reluctance to involve the patient that is causing delay to implementation of personally-held records, or are we too busy? Certainly there is no mention of it in the nGMS contract. Time is short – implementation should be completed by 2006. One area of concern where empowerment is vital is medication taking, bearing in mind that about half of patients with a chronic illness do not take their medication as prescribed (Marinker and Shaw, 2003). We need to explore why and attempt to tailor therapies to suit the individual.

However, it is not all doom and gloom. It is now possible to print out diabetes clinic templates for the patient without the additional filling-in of cards. In my practice, patients have all of the information discussed at the clinic with agreed goals and targets without me writing a thing. I put the relevant details on the computer template and the rest is printed for me. This is one giant step towards patient empowerment without ticking any nGMS boxes. Other examples of good practice are available in The Role of Nurses Under the New GMS Contract (NHS Modernisation Agency, 2003).

Clinical care of adults (covered in Standard 4 of the NSF for diabetes, Table 1) is where the NSF comes into its own and where ticking boxes and patient care would coincide if nGMS targets were a bit higher. Where is the incentive to tackle ‘all’

patients in the nGMS contract when targets are reached or achieved? I have heard disturbing reports of practices not pursuing at risk groups because they have reached their targets. This is lamentable. Inequalities around the house-bound, those in care, those for whom English is not their first language, and those who do not attend the practice for whatever reason, need to be addressed.

Points mean prizes, but to achieve this we must involve the patient

Having a record of HbA1c in the last 15 months attracts three nGMS points but getting it down to 7.4 % or less gains 16. Points in this case do mean prizes; practices are funded on achievement of these clinical indicators. Eleven points are awarded for HbA1c of 10 % or below so there should be no mad rush to get all patients down to the magic 7.4 % if it compromises their quality of life. It is no use getting an individual’s blood glucose down so far that they risk having a hypoglycaemic attack, breaking their leg when they fall over in the process. We must use our common sense here and fully involve the patient in the decision making. This requires patient education and patient empowerment, such as that encouraged by the Expert Patient programme (http://www.expert patients.nhs.uk/, accessed 28.02.05).

The majority of young people with diabetes will be seen in secondary care. However, we should not assume this to be true. Care of young people is covered in Standards 5 and 6 of the NSF Standards document (Table 1). The NSF encourages us to find out what is happening to all of our patients with diabetes. It is worth while making sure.

NSF Standard 7 (Table 1) covers diabetes emergencies. Although rarely the province of the practice nurse to manage diabetes emergencies, hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, illness and non- ketotic coma, we need to be aware of them in order to inform our patients. If the average practice-nurse clinic appointment is 20–30 minutes, is it really possible to explain all of the test results, check the feet, take blood pressure and test urine, tick all the nGMS boxes and provide a high level of education? Anyone trying to accomplish the caring element in less time than that must be super nurse… or a doctor!

NSF Standards 8 and 9 (see Table 1) generally do not impinge on practice nurses and they are not included in nGMS. However pre-conception advice may be relevant and brought to the notice of the practice nurse during some other consultation. Tight blood glucose control is advocated from the time of conception onwards and should be a part of our care plans.

Management of long-term complications

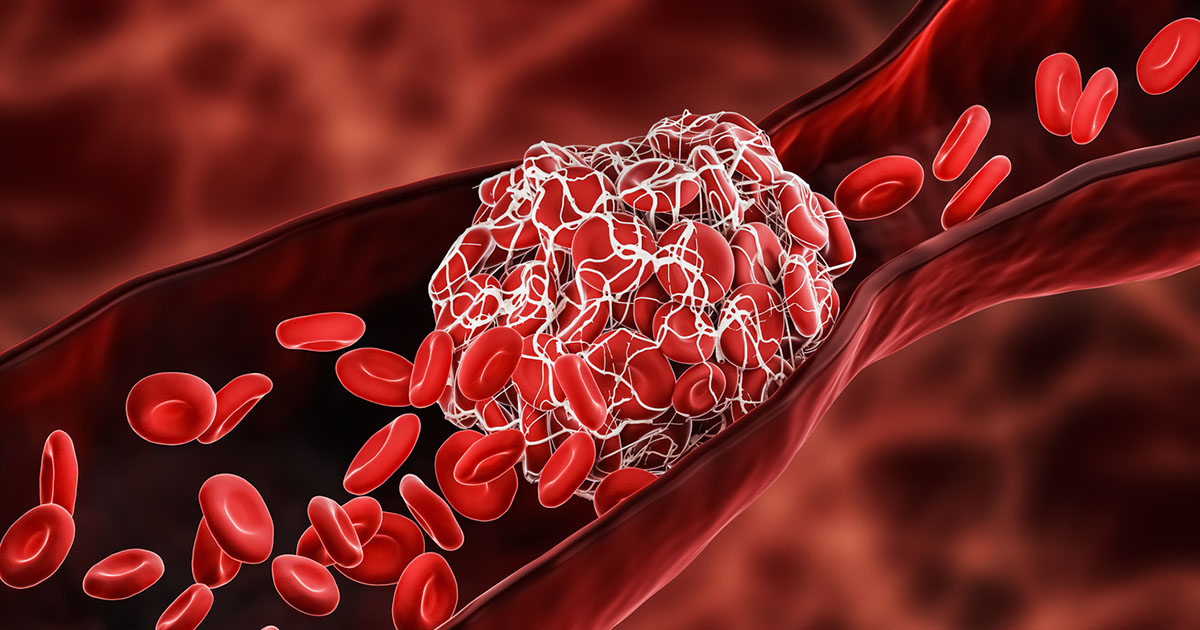

The nGMS contract again returns to the fore in detection and management of long-term complications (corresponding to NSF Standards 10, 11 and 12, Table 1). The clinical indicators not mentioned yet figure largely here and encourage us to see diabetes not as a condition requiring just good glucose control but treatment in a holistic manner. Diabetes is never a mild disease. According to Alan Milburn, in the foreword to the NSF (DoH, 2002), it is the biggest cause of kidney failure, the leading cause of blindness in adults of working age and one of the biggest causes of lower limb amputation, as well as significantly increasing the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Definitely never mild.

The NSF made eye screening a priority and even promised some funding for new services. By 2006 a minimum of 80 % of people with diabetes are to be offered screening, by 2007 100 %. But not just any old screening – properly checked and evaluated. Some areas have enviable systems in place already but others have not even started. In my area we rely on optometrists to screen for retinopathy, but there is no quality assurance on how it is done and what the result is. The nGMS contract provides five points for recording that screening has been done but how about the quality of that screening? It is lamentable that some of us have been lobbying for this service for years without success. However, I do feel that it will now come since it has been given such a high priority in the guidance.

But is nGMS encouraging ‘care’? Smoking cessation is a good example of a useful quality indicator; there are three points for recording status but five for giving smoking cessation advice. Sadly not so for improvements in diet or physical activity; both key elements of the NSF but not included in nGMS contract. We get points for ticking the boxes on foot examination, peripheral pulses and neuropathy testing. What we do not get is any reward for action on the results. Likewise creatinine: test it and you get points; but what if it is raised and they are on metformin? I have even had reports of patients returning from renal clinic on metformin, although it is contraindicated if creatinine is even mildly raised (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002). And what about exception reporting? A patient can be excluded from targets, but there must be a good rationale for so doing. Just because they have not turned up does not mean they are not worthy of recall – and the nGMS contract says three times annually (Table 3, A).

Providing a patient-friendly service

We must be sure though that we are providing a patient-friendly service. Patients interviewed by the Audit Commission (2000) expressed concern over diabetes services, yet there have been some wonderful examples of innovation in practice, which can be seen on the Diabetes UK and the DoH websites: www.diabetes.org.uk/good _practice, accessed (28.02.05), www.publications .doh.gov.uk/nsf/diabetes/goodpractice/introducti on.htm (accessed 28.02.05). We need to think, and work, differently but retain the team approach that is so successful (NHS Modernisation Agency, 2003).

The NSF suggests local approaches to implementation that could include ‘appropriate psychological support’ and the opportunity to participate in structured (usually group) education. Have you got this yet? Additional training is required if we are to be effective in this role (Wilson, 2004). It further suggests that all new patients and those at risk have a care plan, patient- held record and a locally named contact for support. The date for this? April 2003! Have you done this yet?… or are we too busy ticking boxes to generate income for the practice and forgetting how to care?

Well, no actually. Nurses are expected to be involved in the decision-making processes in their practice according to the nGMS contract. All of our training and intuition leads us to care. I am sure we will continue to work with patients to enable them to make the choices that will best enhance their quality of life. If we get the brownie points at the same time, that will be a bonus.

Small increases in three lifestyle behaviours is effective in reducing all-cause mortality.

27 May 2025