The diabetes National Service Framework (NSF) when it was released was seen to be very different from those that had been published before. As an example, the NSF for Coronary Heart Disease (Department of Health [DoH], 2000), published a number of months before the diabetes NSF (DoH, 2001), was a much bigger document that contained a lot of detailed targets and milestones for implementation. The diabetes NSF, especially in its Delivery Strategy (DoH, 2002), has very few specific targets.

In contrast, the new General Medical Services (nGMS) contract Quality and Outcomes Framework (QoF) for diabetes has 18 quality indicators in which 99 quality points can be obtained through delivering high quality diabetes care (British Medical Association, 2003). It is almost as though the new contract provides the detailed targets and milestones missing from the NSF.

It is my view that when taken together the NSF and nGMS QoF give a balanced whole to provide the standards, policies, details and incentives to deliver good quality diabetes care.

Achieving good scores

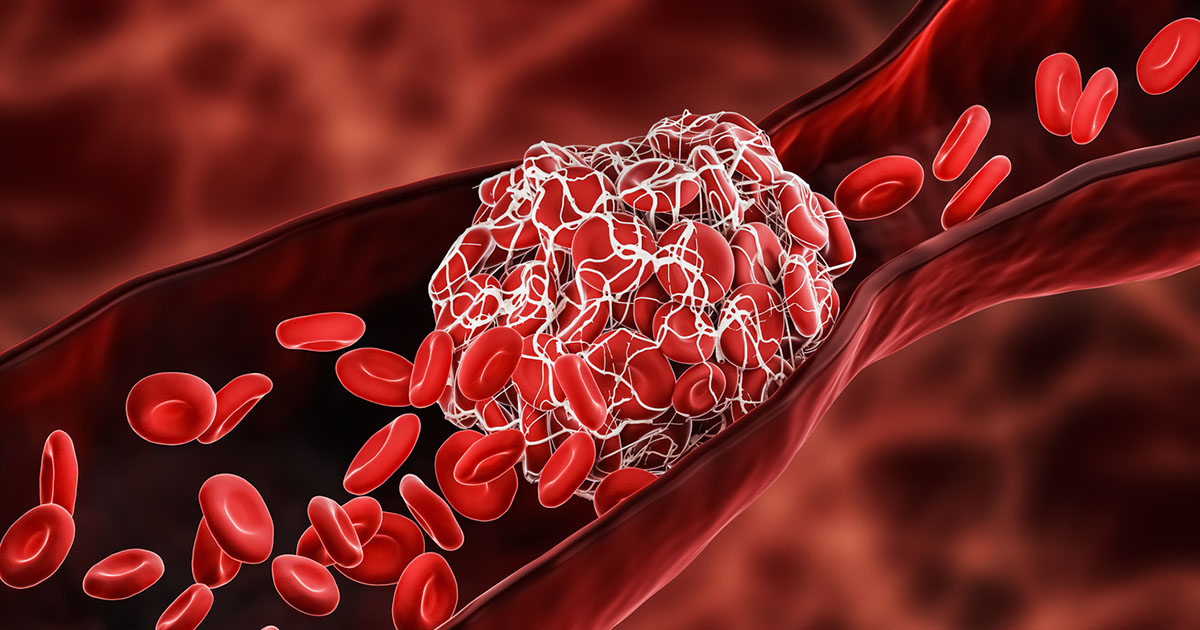

In the nGMS contract, recording process of care will achieve some of the points, but in order for a practice to achieve high points scores they will need to get as many of the points for good quality HbA1c, blood pressure and cholesterol levels as possible. The quality standards are based on a robust evidence base. This means that through achieving quality points there will be reductions in the adverse outcomes of macrovascular and microvascular disease for people with diabetes. In my view, achieving good points scores in the quality framework will save lives, and reduce the number of strokes, amputations, and heart attacks suffered by people with diabetes.

Putting the person with diabetes at the centre of care One unique feature of the diabetes NSF is its emphasis on putting the person living with diabetes at the centre of care. Standard 3 of the NSF, entitled ‘Empowering people with diabetes’ states that ‘All children, young people and adults with diabetes will receive a service which encourages partnership in decision making, supports them in managing their diabetes and helps them adopt and maintain a healthy lifestyle’. This will be reflected in an agreed and shared plan in an appropriate format and language.

‘Where appropriate, parents and carers should be fully engaged in this process.’

The NSF documents very strongly commend the ideas of patient education, choice and empowerment. They encourage high-quality diabetes care, with the potential to attain high scores in the process and QoF.

When the benefits of good glycaemic, blood pressure and cholesterol level control have been clearly explained, the person with diabetes can work at the aspects of diet, exercise and concordance with treatment that will enable the targets to be met. When the person with diabetes does not understand the benefits of lifestyle change and taking tablets to prevent adverse outcomes, they are less likely to comply with treatment and so process and quality targets will not be achieved.

However, there are people living with diabetes who are educated and empowered and who choose, for example, not to run their glycaemic control at an HbA1c level of 7.4 %, but rather at something a little higher. They decide that HbA1c levels in the range 7.6–7.8 % suit them and their lifestyle better.

The case history (below) illustrates when a person chooses not to aim to achieve the HbA1c target of 7.4%, for very good personal reasons. This is patient empowerment and choice in action. The reasons why this person chooses to maintain an HbA1c above target should be recorded on the practice clinical computer system, and an exclusion code used so that their choice need not adversely impact on point scoring for the practice.

Case study

Ms JG is 29 and has had type 1 diabetes for 17 years, and has four insulin injections daily. She is a professional actress. She has an excellent knowledge of her diabetes and uses her skills to vary her insulin doses with her varying levels of exercise and food intake.

She is very frightened of having a hypoglycaemic episode while on stage. She knows the evidence that tight control of her blood sugar levels will reduce the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications, but at the expense of an increased risk of hypoglycaemia. She therefore chooses to maintain an HbA1c level of around 7.8%, which she feels is the best compromise for her, between reducing risk of complications and having a negligible risk of hypoglycaemia.

Balancing targets with patient benefits

There is also the paradox that getting a person to reduce their HbA1c from 7.6 % to 7.3 % hits a target, and ‘targets means points’ and ‘points means money’; but that sort of drop is likely to be of little clinical significance! However, getting a person to reduce their HbA1c from 10.5% to 9.0 % earns no points and no money but is very significant in reducing the risk of adverse outcomes. This is an inevitable consequence of having fixed clinical indicator targets.

Good professional diabetes healthcare education should ensure that people understand the value of reducing HbA1c, blood pressure and cholesterol towards targets, even if the threshold target for earning points is not met. People need to be encouraged to do all they can to move towards the targets. Once the person is nearer the target, there is a possibility that they might actually achieve the target at some time in the future.

Missing targets: patient education

I would have liked to have seen a clinical indicator for patient education in the diabetes QoF. It is possible that some practice nurses may feel under such time pressure to complete all of the clinical indicator fields on the computer template, that it will mean a reduction in time available to chat to and educate the person with diabetes. This might be seen as acceptable as education is not included as a target in itself.

Conclusion

As I have already argued, education and empowerment underpin good quality diabetes care. Well-educated and empowered patients are more likely to be motivated to achieve targets, so missing out on education and support will be counter-productive. It may be necessary to slightly extend the appointment time for routine annual review visits to enable education and recording of the data on clinical indicators to be achieved.

In some practices healthcare assistants are being employed to ensure that the routine information – such as laboratory results, weight measurement, urine testing information, and retinal screening results – are added onto the diabetes computer clinical template, before the person with diabetes sees the practice diabetes nurse. The nurses are then able to spend more time on education, support and encouragement for people with diabetes, reviewing of treatment, and foot screening. The financial incentives that arise from the nGMS contract diabetes QoF may encourage such changes in skill mix to occur in the practice.

Small increases in three lifestyle behaviours is effective in reducing all-cause mortality.

27 May 2025