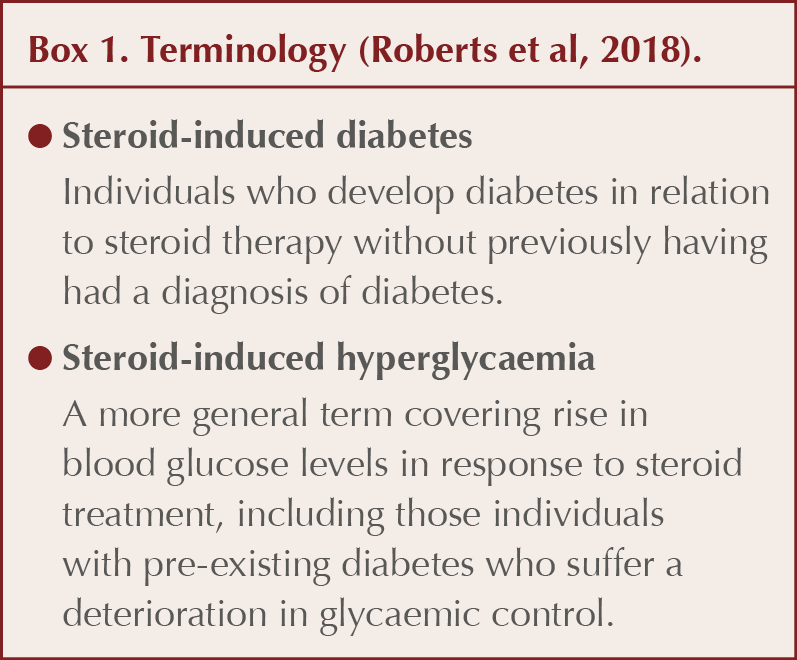

A challenging problem faced in primary care is that of elevated blood glucose as a consequence of receiving steroid therapy. The term steroid, used in this article, refers to glucocorticoids (corticosteroids), which mimic the action of cortisol, the endogenous corticosteroid produced in the adrenal cortex. Amongst their actions, glucocorticoids exert a powerful effect on carbohydrate metabolism, in contrast to mineralocorticoids, such as fludrocortisone, which, like endogenous aldosterone, act via the kidney to influence electrolyte balance.

Prednisolone is the most commonly used steroid in primary care, accounting for over 90% of cases of steroid usage in the UK. Respiratory conditions (such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]) are responsible for around 40% of cases of steroid use within the community (Fardet et al, 2011; Roberts et al, 2018). Initiation of prednisolone for polymyalgia rheumatica (and temporal arteritis) is also common in primary care. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant properties of steroids are utilised in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia gravis, sarcoidosis, autoimmune renal disease, inflammatory bowel disease, a variety of skin conditions, allergic reactions and in post-transplant treatment regimens. Steroid replacement therapy is necessary in Addison’s disease and steroids can also be beneficial in end-of-life care.

Whilst the majority of steroid courses are of short duration (e.g. rescue therapy for acute exacerbations of asthma and COPD), longer courses (e.g. for polymyalgia rheumatica) will require greater surveillance and care, with dose tapering to avoid the consequences of adrenal suppression. An estimated 22% of steroid use continues beyond 6 months (Roberts et al, 2018).

It is important to identify and manage hyperglycaemia in relation to steroid use to relieve symptoms and minimise the risk of acute and long-term complications. There is, however, limited evidence available to guide best management of steroid-induced diabetes and hyperglycaemia. Consequently, management is largely guided by clinical experience and expert opinion (Mills and Devendrea, 2015; Suh and Park, 2017).

Prevalence

A retrospective cohort study in an elderly population found that the risk of developing diabetes was significantly more likely in those initiated on an oral steroid compared to a control group (odds ratio, 2.31 [95% confidence interval (CI), 2.11–2.54]; Blackburn et al, 2002). A study using a primary care database found a lower odds ratio of 1.36 (95% CI, 1.10–1.69) for diabetes associated with three or more oral steroid prescriptions versus no steroid use. There was no association of diabetes with injected, inhaled or topical steroids, or steroid eye drops (Gulliford et al, 2006). Other studies have found a prevalence of steroid-induced diabetes in between these estimates, probably reflecting dose, potency and duration of steroid therapy (Pilkey et al, 2012; Suh and Park, 2017).

A recent meta-analysis of studies evaluating the occurrence of hyperglycaemia in individuals without diabetes treated with systemic steroids found that the rates of steroid-induced hyperglycaemia and steroid-induced diabetes were 32.3% and 18.6%, respectively (Liu et al, 2014).

How do steroids induce hyperglycaemia?

The activity of steroids is mediated via intracellular binding to a cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptor, which then enters the cell nucleus and acts on gene transcription (Roberts et al, 2018). The products of gene transcription exert a powerful anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant activity as well as impacting on glucose metabolism.

Steroids increase insulin resistance in muscle and adipose tissue, reducing peripheral glucose uptake. Hepatic insulin resistance is also increased, releasing the brakes on hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis). Insulin production and release from pancreatic beta-cells is decreased by steroids. These mechanisms contribute to hyperglycaemia and predispose the individual to diabetes (Geer et al, 2014; Tamez-Perez et al, 2015).

The mechanism of action of steroids means that glucose levels will typically rise a few hours after taking oral steroids. Furthermore, it is understood that hyperglycaemia induced by steroids is manifested principally in rises in post-prandial blood glucose levels rather than fasting blood glucose levels (Mills and Devendrea, 2015; Clore and Thurby-Hay, 2009). These observations have important clinical implications for treatment, which will be examined in the next issue of the Journal.

High-risk situations

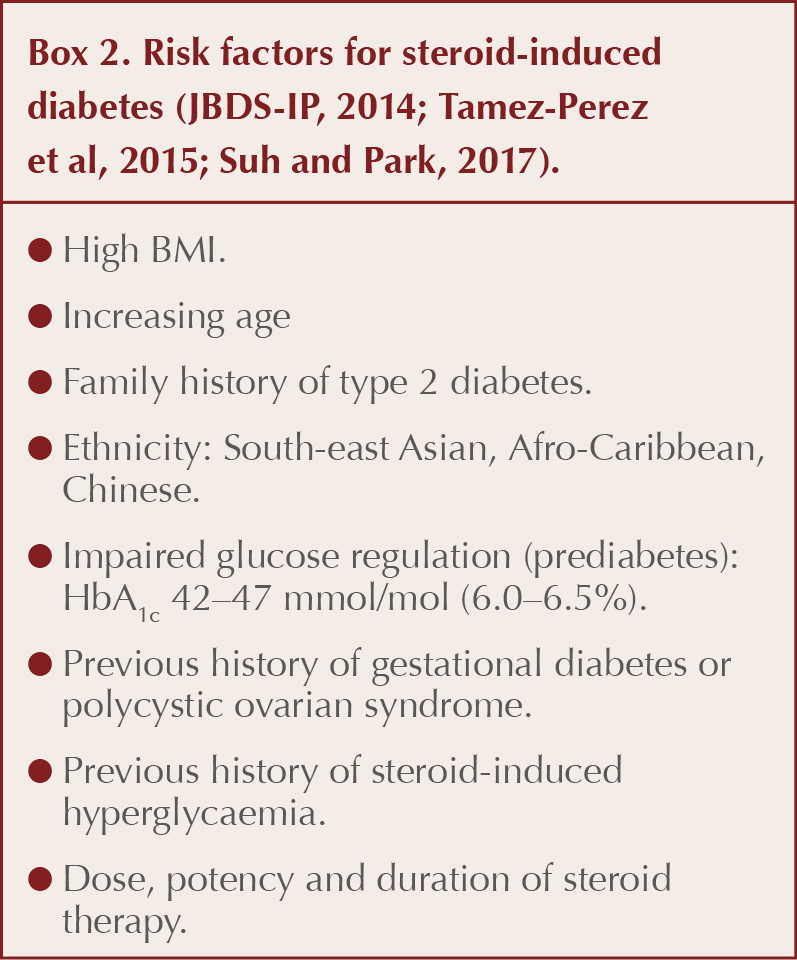

A range of factors predicting the likelihood of steroid-induced diabetes occurring is listed in Box 2. In individuals with a high-risk profile taking more than a brief course of oral steroids, screening for hyperglycaemia is warranted.

Typically, hyperglycaemia is observed when supraphysiological doses of steroid are employed; in the case of prednisolone, this would equate to doses exceeding 5 mg daily (Suh and Park, 2017). The doses of other steroid molecules equivalent to 5 mg daily prednisolone (based on their anti-inflammatory activity) are listed in Table 1.

The higher the dose and the greater the potency of the steroid, the greater is the risk of steroid-induced diabetes (Gurvitz et al, 1994; Clore and Thurby-Hay, 2009). Examples of such situations are the use of high-dose prednisolone in temporal arteritis or the use of dexamethasone in oncology patients. In practice, particular attention to hyperglycaemia should be given in daily doses of prednisolone >20 mg, hydrocortisone >50 mg and dexamethasone >4 mg (Suh and Park, 2017).

Why is steroid-induced hyperglycaemia important?

If blood glucose levels rise sufficiently in response to steroid therapy, an individual may become symptomatic with thirst, polyuria, weight loss and fatigue. Under these circumstances there is a risk of progression to hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state (HHS) or diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) requiring hospital admission for rehydration and control of glucose levels (Tamez-Perez et al, 2015).

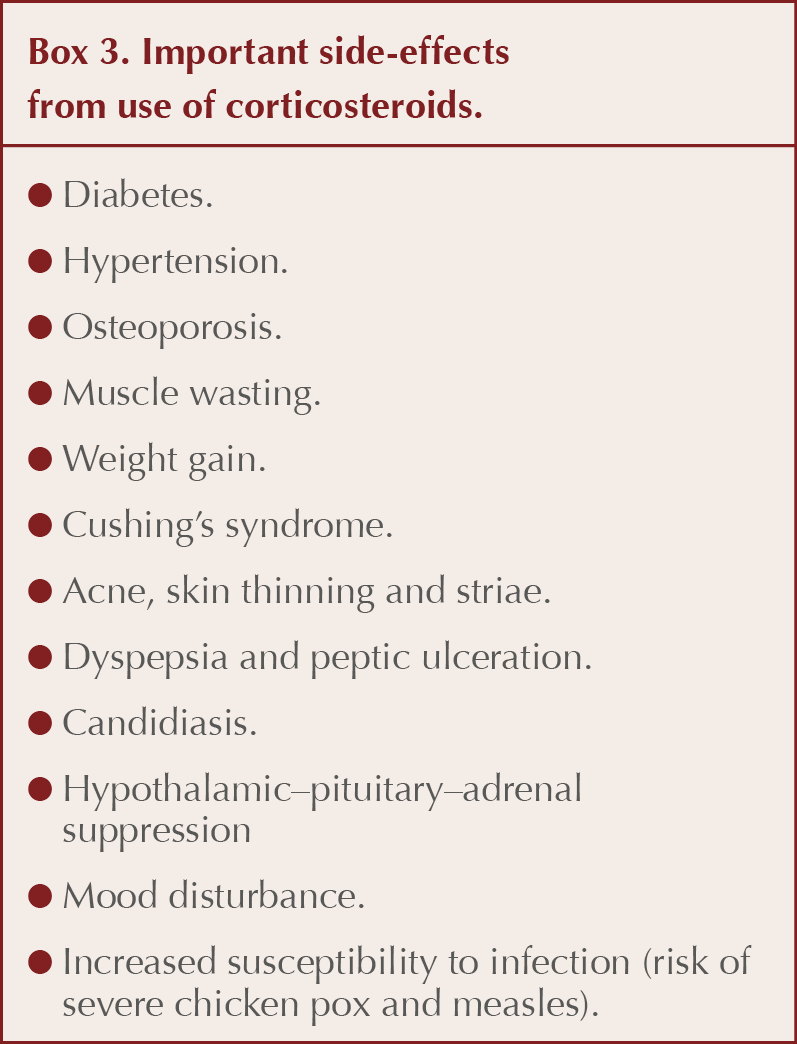

In the longer-term, steroid-induced diabetes, as with other types of diabetes, places the individual at risk of microvascular (nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy) and macrovascular (cardiovascular) complications. Box 3 lists important side-effects from use of steroids.

In the next issue of the Journal, the author will cover the management of steroid-induced diabetes and hyperglycaemia in primary care.

.png)

Jane Diggle discusses emotional health and diabetes distress, and offers some tips for discussing this in our consultations.

11 Nov 2025