Social media is a core part of 21st-century life. At the end of 2020, there were 192 million active daily Twitter users sending 500 million tweets per day (Lin, 2021). This rich source of data has led to a huge increase in social media-based research for applications such as health, politics and natural disasters (Karami et al, 2020). Understanding what information people are seeking and discussing on social media can aid organisations in planning social media campaigns (Harris et al, 2013) and, in a healthcare context, help to identify patient priorities and experiences in a setting where traditional power imbalances are greatly reduced.

Diabetes is a chronic, life-long condition. It has been estimated that people with diabetes spend, on average, 3 hours per year with a healthcare professional (HCP; Roberts, 2007). Constant self-management is crucial in diabetes, and peer support has been shown to be beneficial in aiding it (Heisler, 2007; Dale et al, 2012; Fisher et al, 2012).

Many people with diabetes seek health information online, including through social media sources within the diabetes online community (Kaufman, 2010; Shaw and Johnson, 2011; Reidy et al, 2019). Given its ever-increasing role in modern life, it is unsurprising that people also use social media to interact with others who live with diabetes to share experience and knowledge, and gain emotional and educational support. Diabetes online communities can be particularly useful for individuals with type 1 diabetes, or other rarer types of diabetes, who may struggle to meet others with the same condition in “real world” situations. The World Health Organization (WHO) has suggested that peer support is a promising approach for diabetes care as it harnesses the ability of people to support each other in managing their everyday lives (WHO, 2008). Social media has evolved to offer a far-reaching communication tool that has the potential to support diabetes management by providing access to health information and peer support for social and emotional wellbeing.

During the first wave of COVID-19 in the UK in March 2020, many diabetes healthcare teams were redeployed to provide urgent COVID care, and outpatient appointments were largely cancelled (Forde et al, 2021). Face-to-face peer support became impossible owing to lockdowns and social distancing requirements, placing many in a position of extreme isolation. While many postulated that this would have a significant and global negative effect on all affected (Brooks et al, 2020; Greenberg et al, 2020; Ho et al, 2020; Mental Health Foundation, 2020), and particularly on those with additional vulnerabilities such as diabetes (Stewart, 2020), the speed at which the pandemic developed and its catastrophic effects on daily life meant that many opportunities to research the impact of the pandemic on the psychological health of those with diabetes were not taken. What little research has been carried out has come to mixed conclusions (Joensen et al, 2020; Forde et al, 2021; Madsen et al, 2021), and it is likely that the true effects of the pandemic may take years to emerge.

Given that social media was already highly used by people with diabetes prior to the pandemic, and that during the pandemic it became a primary source of information, connection and support for many, it is likely that, by examining the themes within the online discourse of people living with diabetes during the pandemic, we can gain insight into their anxieties and priorities during this remarkable period. Twitter is seen as a useful source of data as it is publicly available and easily accessible. As all users sign up to terms and conditions, ethical approval is currently not required for accessing and analysing tweets. This makes Twitter one of the most used social media platforms for academic research.

Aims

This study aimed to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the diabetes-related discussions of people living with type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and healthcare professionals.

Methods

Data extraction

Although Twitter allows academics to retrieve data, it only permits a small portion of relevant tweets to be accessed. It can be costly, and researchers need data analysis skills. Therefore, we used a company, CREATION.co, to extract 100% of tweets related to diabetes over the study period. CREATION.co used a third-party platform called Brandwatch to extract, store and analyse the data. CREATION.co (including its CREATION Pinpoint® service) is an approved partner of Twitter, and accesses and analyses data within the Twitter guidelines. CREATION Pinpoint’s privacy policy can be accessed here (CREATION.co, 2021).

Identifying people with diabetes on Twitter

The study investigated UK-based Twitter users with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. People with diabetes were identified based on: (1) self-verification through their Twitter bio, and (2) through their public Twitter conversations. A keyword rules-based algorithm was used to find the profiles most likely to be of people with diabetes; their Twitter bios were then confirmed manually. Examples of keywords include: person living with diabetes, person with type 1 diabetes, person with type 2 diabetes, etc.

1. An individual who self-identified as having diabetes within their Twitter bio was classified as a person with diabetes. Twitter bios were searched using key terms that identified users with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. This method identified 1525 people with type 1 and 252 people with type 2 diabetes in the UK.

2. An individual who self-identified as having diabetes through their Twitter posts was classified as a person with diabetes. Original (as opposed to retweeted) Twitter posts that identified the author as a person with diabetes were gathered and subclassified into type 1 or type 2 diabetes using key terms. This method identified a further 661 people with type 1 diabetes and 534 people with type 2 diabetes.

Therefore, this study analysed the Twitter conversations of 2186 UK people with type 1 diabetes and 786 UK people with type 2 diabetes. With an estimated 390000 people living with type 1 diabetes in the UK and 3.5 million people with type 2 diabetes, our sample represented 0.56% and 0.02% of these populations, respectively.

The accuracy of the classification by key term method was analysed. Random samples of 100 users from the type 1 category and 100 users from the type 2 category were manually verified. This confirmed the key term verification to be performing at 98% accuracy.

Classifying diabetes conversations

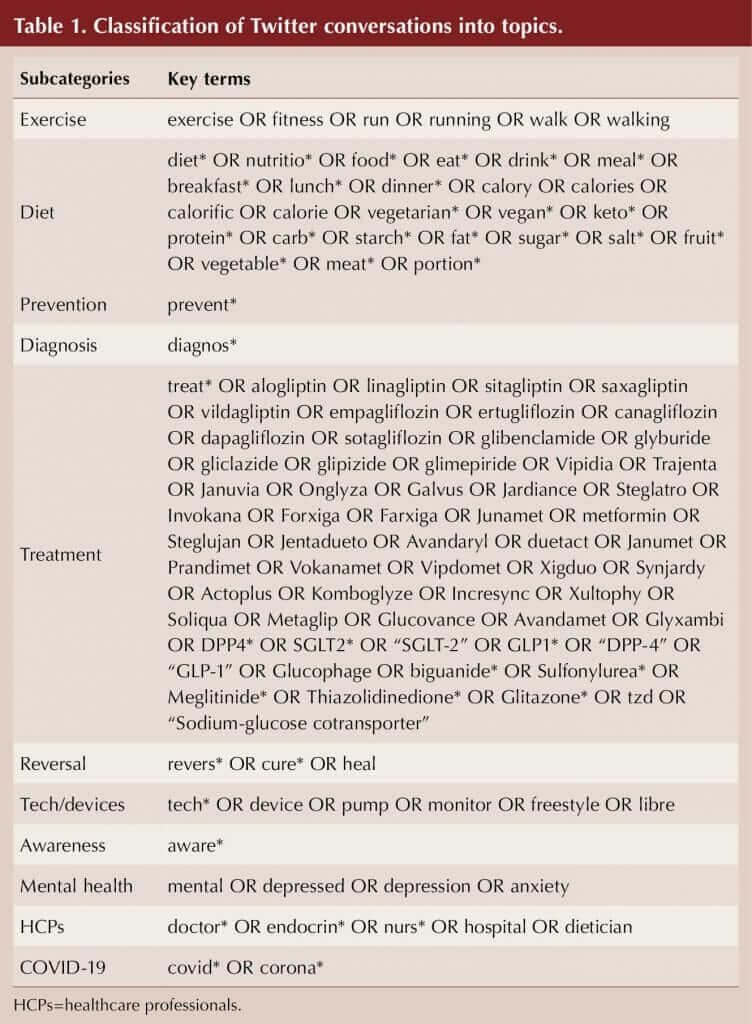

Twitter posts published by verified people with diabetes between 1 January 2019 and 30 September 2020 (638 days), and containing keywords associated with diabetes, were extracted. Key terms were used to further segment relevant Twitter posts into 11 subcategories: exercise; diet; diagnosis; prevention; treatment; reversal; tech/devices; awareness; mental health; seeing a HCP; and COVID-19 (Table 1). Posts were classified into the subcategories using the key terms by a rules-based algorithm. The rules for key terms were created with Boolean logic, with the following operators separating the terms: OR – either terms separated by or need to be matched; AND – both terms separated by and need to be matched; * – any characters following can be matched. Multiple categories were allowed (i.e. if a post contained both diet and exercise, it was classified in both topics).

Findings

During the 638-day period, 114,005 diabetes-related Tweets were posted from users in the type 1 group, and 31,114 posts were posted from users in the type 2 group.

Tweets from people with type 1 diabetes

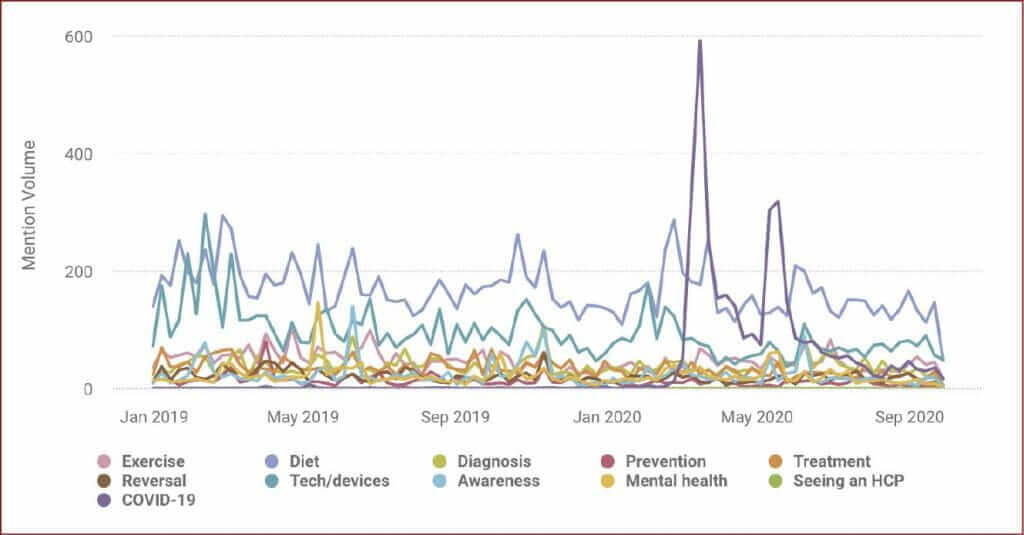

For people with type 1 diabetes, the primary topics of diabetes-related discussion between January 2019 and January 2020 (i.e. before the pandemic) were diet (15,275 posts) and technology/devices (8659 posts), with a spike in discussion in May 2019 for mental health (Figure 1).

In March and May 2020, there were increases in posts relating to COVID-19, with a peak of 588 on 16 March (the start of the first lockdown in the UK) and a secondary peak of 388 on 18 May (around the time when loss of taste and smell were added to the list of symptoms and UK nations began discussing the easing of lockdown restrictions). The increase in conversations around COVID-19 coincided with a decline in those around each of the other categories. For example, during the 27 weeks before 16 March the average number of posts per week about diet was 171.1, compared to 145.6 in the subsequent 27-week period, representing a 14.9% decrease. The change in volume of technology/devices conversation was even more stark. In the 27-week period leading up to the 16 March, people with type 1 diabetes posted an average of 95.4 posts per week in this category, compared to 64.5 after, a decrease of 32.4%. The level of conversation around awareness, mental health, prevention, treatment and reversal also decreased after the COVID-19 spike. Posts about exercise increased and the diagnosis conversation was relatively unaffected.

The main changes in conversation volumes before and after the COVID-19 spike in March 2020 were a reduction in the awareness (−40.4%), technology/devices (−38.2%) and prevention (−25.4%) categories.

Tweets from people with type 2 diabetes

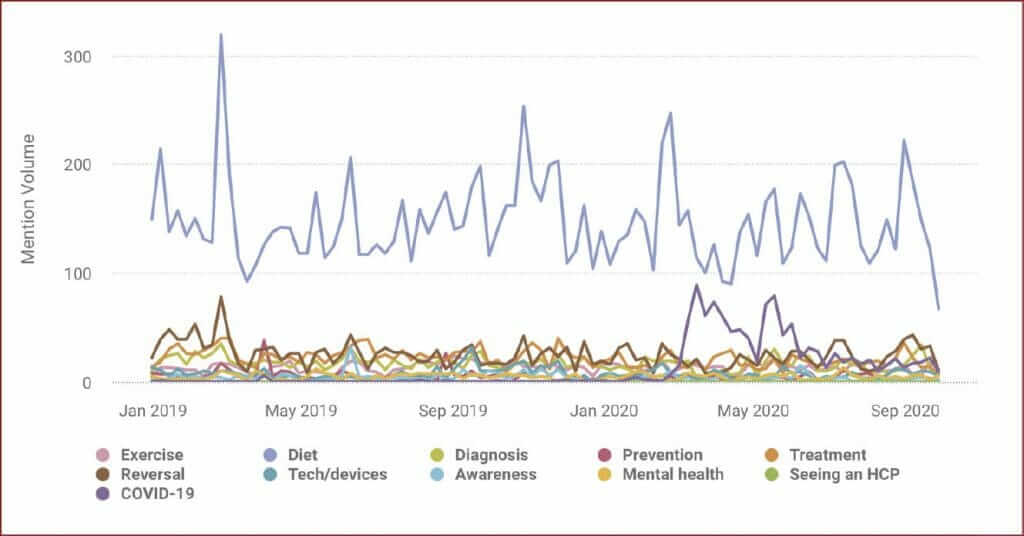

For people with type 2 diabetes, the biggest topic of conversation during the study period was diet (Figure 2), as it was with people with type 1 diabetes. However, technology and devices did not feature as highly in the conversations of people with type 2 diabetes as it did in those of people with type 1 diabetes. There was a spike in conversations about reversal of type 2 diabetes and diet corresponding with Diabetes Prevention Week in April 2019. There was also a spike in conversations about COVID-19 on 16 March and 18 May 2020 (88 and 78 posts, respectively), but not at the levels seen for people with type 1 diabetes.

Besides COVID-19, all topics saw a decrease in average daily posts during the first lockdown compared to the 439 days prior. However, a number of topics have been re-emerging with an increase in average daily posts since 3 July 2020 (when some lockdown restrictions were eased), but not to pre-lockdown numbers.

Tweets from healthcare professionals

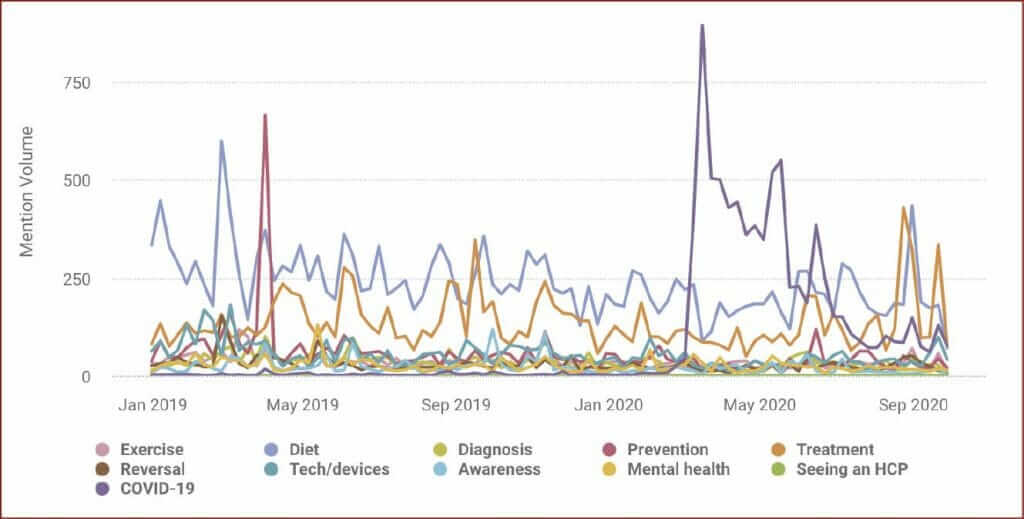

During the 638-day study period, 128901 social media posts from 12045 UK HCPs were published. Between 1 January 2019 and March 2020, diet and treatment were the most discussed diabetes-related topics in this group (Figure 3). In April 2019, there was a spike in conversations about prevention of type 2 diabetes, again corresponding to Diabetes Prevention Week.

As there were with people with diabetes, conversation spikes in diabetes posts relating to COVID-19 occurred on 16 March and 18 May 2020, with the level of such posts remaining high in the intervening time. This period of heightened COVID-19 conversation coincided with a 13.1% decline in posts about treatment (111.4 weekly posts before the conversation spike versus 96.8 during it). During the same period, the number of weekly posts about diet declined by 12.2%.

After the heightened period of COVID-19 posts, volumes of posts on treatment and diet recovered to baseline. Treatment conversations spiked in September 2020, corresponding to the European Association for the Study of Diabetes conference, which was held virtually for the first time. For HCPs, with the exceptions of awareness and mental health, all topics of conversation have been increasing since the first full UK lockdown eased in May/June 2020.

Discussion

This study highlights how people with diabetes and HCPs use Twitter for education and peer support related to diabetes. The most talked about diabetes-related topic prior to COVID-19 and lockdown in the UK, for those with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes as well as for HCPs, was diet. For those with type 1 diabetes, technology/devices was also widely discussed, as was treatment by HCPs. Once COVID-19 hit the UK in March 2020, all groups showed a decrease in the other topics discussed and a spike in discussions around COVID-19, although for those with type 2 diabetes this was to a lesser degree.

Over the 638-day study period, the discourse was fairly consistent with the major disruption in the topics of conversations being caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. There is also some evidence of public health campaigns (e.g. Mental Health Awareness Week, the launch of a national diabetes mental health report [Flury and Solomons, 2019] and Diabetes Prevention Week) having an impact on changing the conversations, although not to the extent that COVID-19 did. This indicates that people living with diabetes engage with and discuss the themes of awareness-raising campaigns.

Spikes were also observed in relation to societal concerns post-COVID-19; the increase in posts around exercise following the first COVID-19 spike could be explained by the national lockdown in the UK when people were allowed only limited amounts of outdoor time for exercise. In addition, evidence had been published showing COVID-19 disproportionately affecting people considered overweight or obese.

Social media is being used more frequently by people with health conditions to provide immediate and interactive health advice. However, there are some pitfalls to social media that need to be considered, such as the accuracy and reliability of information; people’s ability to assess the credibility of information; the potential for cyber bullying; and a potentially detrimental effect on the patient–HCP relationship (Reidy et al, 2019). In addition to seeking health information, people are using social media for peer support. Peer support has been shown to be beneficial in the self-management of long-term conditions, such as diabetes (Heisler, 2007; WHO, 2007; Dale et al, 2012; Fisher et al, 2012). COVID-19 and the inability to meet face to face for peer support and education has made social media platforms more important for these groups.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that only 0.08% the population of people with diabetes in the UK is accounted for. It was not a representative sample as it tended to be skewed towards younger people with type 1 diabetes, who are using technology to aid self-management. In fact, our type 2 group represented only 0.02% of the wider population, which is generally older and subject to higher levels of weight-based stigma. Those who feel a high level of stigma or who are struggling with their diabetes and management may stay away from social media, or at least discussions around these topics, for fear of being judged. In addition, social media “influencers” (individual users with large followings and significant influence) could skew conversations because of the number of followers and their reach.

Our study only analysed the content of tweets that came from accounts identified as belonging to people with diabetes or to HCPs. Key terms within those tweets were then compiled into subcategories. While this helped to ensure that tweets were specifically about diabetes, it is possible that this strategy has been overly specific and that a large number of potentially relevant tweets have been missed. Similarly, there may have been issues with the key term chosen to represent each conversation category. For example, the mental health category does not include the names of any diabetes-specific mental health issues (e.g. diabetes distress, T1DE or “diabulimia”).

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to analyse social media conversations over a 22-month period during which a global pandemic occurred. It highlights the topics of conversations that remained fairly consistent over this period, and the impact that a pandemic and health campaigns can have on changing the conversations.

Conclusion

People with diabetes are using social media to discuss diabetes and to learn more about the condition both from people with diabetes and HCPs. Social media should be used more to help people with diabetes, people with other long-term conditions and HCPs access education and peer support in an easy, informative and engaging manner. Research is needed to better understand how to use social media as a tool for the dissemination of health information, and as a way to engage people living with and managing chronic conditions.

Small but significant 12% increased risk of developing chronic cough compared to treatment with other second-line agents for type 2 diabetes.

8 Dec 2025