Fasting in Ramadan (Sawm) is one of the five pillars of Islam. The other pillars are: Shahada (the declaration of faith), Salah (five daily prayers), Zakat (annual alms tax) and Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca). The Muslim population in the UK is estimated close to 1.6 million people, constituting 2.7% of the overall population (Office for National Statistics, 2001). While diabetes affects 4% of the white Caucasian population, it affects 22–27% of some ethnic groups’ Muslim population between the ages of 25 and 74 years (Hanif et al, 2007). The approximate number of Muslims with diabetes in the UK is estimated at 325 000 (Watkins, 2002).

Although the Holy Quran exempts people with chronic diseases from fasting, there are many people with diabetes who still choose to fulfil their religious beliefs. Fasting may lead to hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia, or both, with or without ketoacidosis. In the past, healthcare professionals have advised people not to fast and, because of this, some people have been reluctant to seek medical advice. However, attitudes are changing as more information is available to help educate healthcare professionals about the cultural aspects of diabetes care.

What is Ramadan?

Ramadan is the ninth month in the Islamic calendar and it lasts 29 or 30 days. Fasting in Ramadan is obligatory upon each sane, responsible and healthy Muslim adult, and it means abstaining from all food, drinks, smoking, and sexual activity from sunrise to sunset. The purpose of the fast is to allow Muslims to seek nearness to God, to express their gratitude to and dependence on him, and to remind them of the needy. During Ramadan, Muslims are also expected to put more effort into following the teachings of Islam by refraining from violence, anger, envy, profane language, and gossip (Qureshi, 2002; Al-Arouj et al, 2010).

The Islamic calendar is based on a lunar calendar, thus the duration of the daily fast varies according to the geographical location and season (Fazel, 1998). In the UK, a fast can last for up to 19 hours during the summer months. Muslims eat two meals during Ramadan, before sunrise (Sehar) and after sunset (Iftar). Certain individuals are exempt from fasting, however many people with diabetes insist on fasting during Ramadan, thereby creating a medical challenge for their healthcare professionals (Karamat et al, 2010).

Effect of fasting on diabetes

In healthy individuals, eating stimulates the secretion of insulin from the islet cells of the pancreas. This, in turn, results in glycogenesis and storage of glucose as glycogen in the liver and muscle. During fasting, insulin secretion is reduced while counter-regulatory hormones glucagon and catecholamine are increased. This leads to glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis and to increased fatty acid release and oxidation that generates ketones that are used for nutrition by the body (Al-Arouj et al, 2010).

In people with type 1 diabetes or severe insulin deficiency, a prolonged fast in the absence of adequate insulin can lead to excessive glycogen breakdown and increased gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis, leading to hyperglycaemia and ketoacidosis. People with type 2 diabetes may suffer similar perturbations in response to a prolonged fast, however ketoacidosis is uncommon, and the severity of hyperglycaemia depends on the extent of insulin resistance or deficiency.

EPIDIAR (Epidemiology of Diabetes and Ramadan) is a large retrospective population-based study looking at diabetes during Ramadan (Salti et al, 2004). It was conducted in 13 countries with 12243 participants, of whom 8.7% had type 1 and 91.3% had type 2 diabetes. In total, 43% of people with type 1 diabetes and 79% of people with type 2 diabetes reported fasting at least 15 days during Ramadan. Insulin dose was unchanged in 64% of participants, and the doses of oral medications were unchanged in 75% of participants with type 2 diabetes. Severe hypoglycaemic episodes were significantly more frequent compared with other months (type 1 diabetes, 0.14 versus 0.03 episode per month; type 2 diabetes, 0.03 versus 0.004 episode per month; P<0.0001). Similarly, the incidence of severe hyperglycaemia was higher during Ramadan. Weight was unchanged in the vast majority of participants with type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Salti et al, 2004).

Takruri (1989) looked specifically at the effects of fasting on body weight and showed a significant weight reduction in overweight, normal weight (controls) and underweight groups. Another study indicated that Ramadan fasting led to a decrease in blood glucose levels; however, it had a significant correlation with weight. Regarding cholesterol, triglyceride and total cholesterol levels did not change before compared with after Ramadan (Ziaee et al, 2006). Mafauzy et al (1990) found a significant increase in the HDL-cholesterol level during Ramadan of 20%; this increase was lost after Ramadan. Other studies also concluded either no change in weight or weight loss in people with diabetes during Ramadan (Mafauzy, 2002; Dikensoy et al, 2009).

Management of diabetes during Ramadan

Pre-Ramadan medical assessment and education

All people with diabetes wishing to fast should receive proper assessment and counselling 1–2 months before the beginning of Ramadan. Advice regarding fitness to fast and associated risks should be given and full assessment should be carried out. It is key to realise that care must be highly individualised and that the management plan will differ for each specific person. People with diabetes may be categorised by the risks associated with fasting (Table 1) (Al-Arouj et al, 2010).

Medical assessment

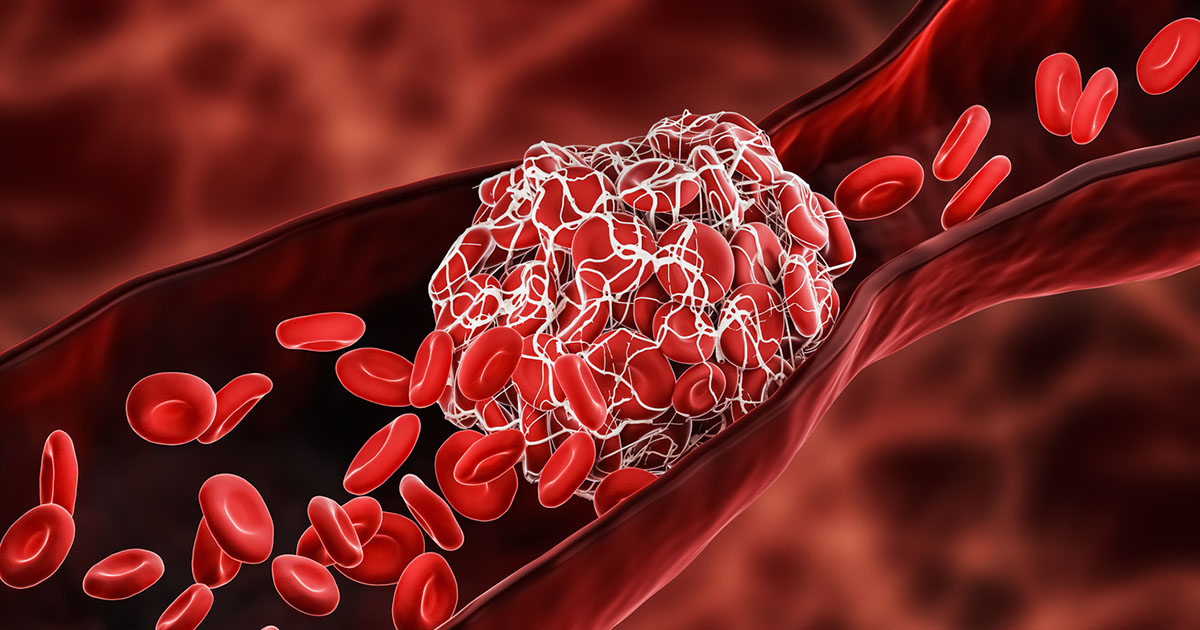

The assessment should include a full annual review, detection of complications along with measurements of HbA1C levels, lipids, renal function and blood pressure. People should be advised about the potential risks of fasting such as hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, dehydration and thrombosis. Medication dosing and timing need to be reviewed and changed as necessary.

Educational counseling

Educational counselling should focus on the individual with diabetes as well as their family and include the awareness of symptoms of hypo- and hyperglycaemia, planning of meals, blood glucose monitoring, administration of medicines, physical activity as well as management of acute complications including when to break the fast (Al-Arouj et al, 2010). Blood sampling, blood glucose monitoring and injections do not invalidate the fast. Muslims are not allowed to smoke during fasting, which provides a unique opportunity to encourage them to quit and to offer help and advice as needed (Aveyard et al, 2011). Health promotional material is published regularly by the Department of Health (Communities in Action, 2007). One study in the UK showed that only 40% of participants received any pre-Ramadan counselling (Sarween et al, 2006).

Dietary advice

It is traditional to break the fast with dates and milk. However, for people with diabetes, dates should be limited to a maximum of three. The common practice of ingesting large amounts of foods rich in carbohydrate and fat, especially at the sunset meal, should be avoided. General healthy diet advice should be followed. Eating a complex carbohydrate meal at dawn and simple carbohydrate at dusk may be more appropriate (Al-Arouj et al, 2010). Adequate fluid intake when breaking the fast should be advised to prevent the risk of dehydration, renal failure and thrombotic events. While a normal level of physical activity is encouraged, excessive exercise may lead to hypoglycaemia and should be avoided.

Exemptions and when to break the fast

Fasting during Ramadan is a central pillar of the Muslim faith, however Islam provides an exemption from fasting when it may adversely affect health (Table 2) (Karamat et al, 2010).

“Those among you, who witness it, let him fast therein. Whoever is sick or on a journey, then a number of other days. God desires ease for you, and desires not hardship…” (Al-Quran, 2: 185).

An international consensus meeting of healthcare professionals and research scholars with an interest in diabetes and Ramadan was held in 1995. It concluded that people with type 1 or unstable type 2 diabetes, people with diabetes-related complications, pregnant women and older people with diabetes should be exempt from fasting (Foundation for Scientific and Medical Research on Ramadan, 1995).

Individuals who decide to fast should be advised to check their blood glucose level regularly and should break the fast if the blood glucose level is <3.3 mmol/L or exceeds 16.7 mmol/L (Al-Arouj et al, 2010). They should also break the fast if the blood glucose level is <4 mmol/L in the morning if the person is treated with a sulphonylurea or insulin (Al-Arouj et al, 2010).

Management of people with type 1 diabetes

People with type 1 diabetes and severe insulin deficiency may have excessive glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis. All of this may lead to hyperglycaemia and ketoacidosis that could be life-threatening. Furthermore, some people with diabetes have autonomic neuropathy leading to hypoglycaemia unawareness.

The general advice for those with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes is that they should not fast (Al-Arouj et al, 2010). A total of 43% of the participants with type 1 diabetes in the EPIDIAR study fasted during Ramadan (Salti et al, 2004). If an individual decides to fast then they should be treated with a basal–bolus regimen preferably using insulin analogues and test blood glucose levels regularly (Al-Arouj et al, 2010). In two small studies insulin glargine has been shown to be associated with less hypoglycaemia than glimepiride and repaglinide (Mucha et al, 2004; Kassem et al, 2005). In another study, glycaemic control was improved and hypoglycaemia was significantly reduced with insulin lispro compared with regular human insulin (Kadiri et al, 2001).

Fasting at Ramadan may be successfully accomplished in people with type 1 diabetes who are treated with an insulin pump if they are fully educated and familiar with the use of the pump and are otherwise metabolically stable and free from any acute illnesses (Al-Arouj et al, 2010). Prior to Ramadan, they should receive adequate training and education, particularly with respect to self-management and insulin dose adjustment. They should adjust their infusion rates carefully, according to results of frequent self monitoring of blood glucose. Most will need to reduce their basal infusion rate while increasing the bolus doses to cover the predawn and sunset meals (Al-Arouj et al, 2010).

Management of people with type 2 diabetes

People with diet-controlled diabetes

Individuals whose type 2 diabetes is controlled by diet should be able to fast without problems. Distributing calories over two to three smaller meals during the no-fasting interval rather than eating one big meal may help to prevent excessive postprandial hyperglycaemia.

People treated with oral antidiabetes drugs

The choice of oral antidiabetes drug (OAD) should be individualised. In general, OADs that act by increasing insulin sensitivity are associated with a significantly lower risk of hypoglycaemia than compounds that act by increasing insulin secretion.

Metformin

Individuals treated with metformin alone may safely fast because the possibility of hypoglycaemia is minimal. The total daily dose should remain unchanged. The morning dose to be taken before the predawn meal and a dose usually taken at lunchtime can be added to the evening dose and taken with the sunset meal instead (Al-Arouj et al, 2010).

Thiazolidinediones

Individuals treated with thiazolidinediones have a low risk of hypoglycaemia. Usually no change in dose is required but it is preferable for medication to be taken with the sunset meal rather than with breakfast (Al-Arouj et al, 2010; Karamat et al, 2010).

Short-acting insulin secretagogues

Short-acting insulin secretagogues, such as repaglinide and nateglinide, are useful because of their short duration of action. They can be taken twice-daily before the sunset and predawn meals. In a study in which 235 people previously treated with a sulphonylurea were randomised to receive either repaglinide or glibenclamide, no differences in HbA1C level were identified and the number of hypoglycaemic events was significantly lower in the repaglinide group (2.8%) than the glibenclamide group (7.9%) (Mafauzy, 2002).

Sulphonylureas

General advice is to use short-acting sulphonylureas with caution during Ramadan (Karamat et al, 2010). People with diabetes treated with a once-daily sulphonylurea (such as glimepiride with breakfast) should be advised to take it with the sunset meal instead. The total daily dose remains unchanged. Individuals taking a shorter-acting sulphonylurea (such as gliclazide twice daily) should continue to take the same total dose each day: one dose with sunset meal and the other with predawn meal. If an individual normally takes a different dose morning and evening he or she should reverse morning and evening doses during the fast (Diabetes Multidisciplinary Team, 2009). If hypoglycaemia occurs during the day, the predawn dose should be reduced and occasionally needs to be stopped completely. Long-acting sulphonylureas such as glibenclamide are best avoided during fasting (Diabetes Multidisciplinary Team, 2009).

An open-labelled, prospective observational study from six countries looked at the use of glimepiride in 332 people with type 2 diabetes. The incidence of hypoglycaemic events was 3% in those newly diagnosed with diabetes and 3.7% in those receiving treatment for their diabetes. These figures were similar to the pre- and post-Ramadan periods (Glimepiride in Ramadan Study Group, 2005).

Incretin therapies

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists act in a glucose-dependent manner and are associated with less hypoglycaemia when compared with conventional treatments (Hassanein et al, 2011), and hence may be suitable for use during Ramadan. However, these are new agents and very few studies are currently available to draw firm conclusions. In a recent prospective study, vildagliptin caused no hypoglycaemia, was well adhered to and improved HbA1C when compared with sulphonylurea as an add-on to metformin in people with type 2 diabetes fasting during Ramadan (Hassanein et al, 2011).

GLP-1 receptor agonists may initially cause nausea and vomiting and this could be a limiting factor during fasting. In Ramadan, when used alone these agents do not require any dose adjustments (Karamat et al, 2010), but the risk of hypoglycaemia in combination with a sulphonylurea remains high, hence the sulphonylurea dose may need to be reduced. A meta-analysis on the randomised controlled trials with exenatide showed that severe hypoglycaemia was rare. Mild to moderate hypoglycaemia was 16% versus 7% (exenatide versus placebo) and more common in people also treated with a sulphonylurea (Chia and Egan, 2008). In general, the incidence of hypoglycaemia with an oral DPP-4 inhibitor was less when compared with glimepiride (Ferrannini et al, 2009). Similarly, a pooled analysis of 5141 people in clinical trials for ≤2 years showed that sitagliptin monotherapy or combination therapy (with either metformin, pioglitazone, sulphonylurea, or sulphonylurea and metformin) was well tolerated and hypoglycaemia only occurred in people on a combination therapy that included a sulphonylurea (Chia and Egan, 2008).

People treated with insulin

Long-acting insulin doses need to be reduced by 20% to reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia (Karamat et al, 2010). Dose alteration should be individualised taking into consideration previous diabetes control and risk of hypoglycaemia. Long-acting insulin should be administered with the evening meal at dusk. Short-acting insulin analogues are also useful during fasting as they can work immediately following meals (Karamat et al, 2010). For premixed insulins, the morning insulin dose should be taken at dusk and half of the evening dose should be taken at dawn (Karamat et al, 2010). Insulin analogue preparations may be more useful than human soluble insulin in managing diabetes during Ramadan to avoid hypoglycaemia (Akram and De Verga, 1999).

Management of hypertension and dyslipidaemia

Dehydration, blood volume depletion, and a tendency towards hypotension may occur with fasting during Ramadan, especially if the fast is prolonged. Hence, the dosage or the type of antihypertensive medication, or both, may need to be adjusted to prevent hypotension. Diuretics may not be appropriate during Ramadan for some people (Al-Arouj et al, 2010). It is common that the intake of foods rich in carbohydrates and saturated fats is increased during Ramadan. Appropriate counselling should be given to avoid this practice, and agents that were previously prescribed for the management of elevated cholesterol and triglycerides should be continued.

Conclusion

The management of a chronic disease like diabetes may be affected by practices related to culture or religion. Fasting during Ramadan is an important pillar of the Muslim faith and most people with diabetes will continue to fast during Ramadan.

Managing Muslim people with diabetes during Ramadan continues to be a challenge. It is important that healthcare professionals are well informed regarding the effects of Ramadan on diabetes; they should be able to offer advice, guidance and change of medications as required during pre-Ramadan counselling to enable individuals to fast safely if they wish to do so. Changes of medications should be individualised depending on diet and lifestyle, risk of hypoglycaemia and baseline glycaemic control. An important part of the management is to educate individuals with diabetes and their family and alter their therapy with clear guidance.

Small increases in three lifestyle behaviours is effective in reducing all-cause mortality.

27 May 2025