We spend the majority of our time in conversation with our patients. As in any situation, the language used is of prime importance, especially in a consultation. How we engage with the person living with diabetes makes a huge difference to whether that person believes he or she is the main focus of the consultation. It is not about numbers and targets, but about the person in front of us.

Why does language matter?

Language is powerful and can impact a person’s perceptions and behaviour. The language we use can therefore have an impact on health outcomes. Positive communication (verbal, written and body language) with people with diabetes can inspire, build confidence, improve wellbeing and self-care; whereas poor communication can leave patients feeling demotivated, stigmatised and hurt, as well as undermining their self-care efforts (Holt and Speight, 2017; NHS England, 2018).

Language is central to personal identity, attitude, social perception, stereotyping and bias (such as gender, religion, health and race; (Dickinson et al, 2017a). We can reinforce negative stereotypes or promote positive stereotypes through our choice of words and phrases (NHS England, 2018). Our use of language therefore has nothing to do with political correctness but affects the core of healthcare professionals’ interactions with and about people with diabetes (Holt and Speight, 2017).

In the past, information has been produced on how to effectively interact with people with diabetes. Until recently, however, there has been little discussion on the language used, despite language being the principal vehicle for sharing knowledge and understanding (Dickinson et al, 2017a). There is a recognised need for a language movement in diabetes care and education (Dickinson et al, 2017a), and momentum for this is building.

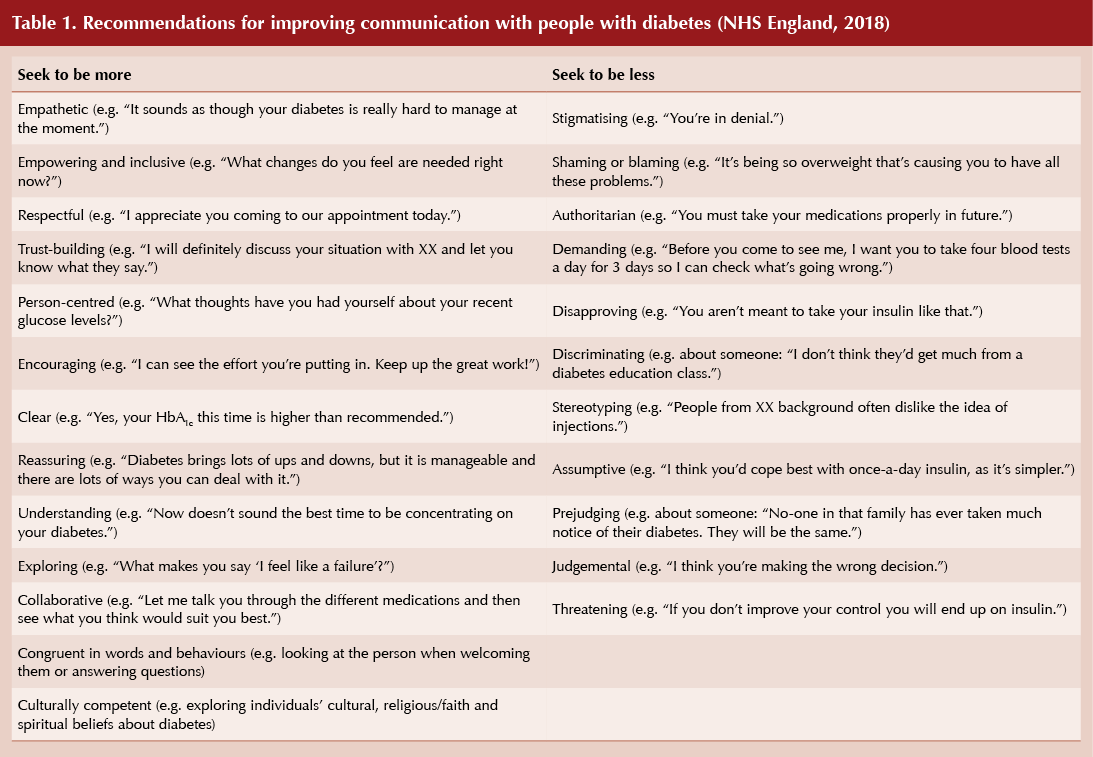

A US task force consisting of American Association of Diabetes Educators and American Diabetes Association members met to discuss the issue of language in diabetes in 2017. The task force came up with a number of recommendations for improving communication with patients, see Box 1 (Dickinson et al, 2017b).

In the UK, a Language Matters Working Group has been set up by NHS England to improve awareness of the impact words may have on the care of people living with diabetes. The Working Group is supported by the Primary Care Diabetes Society (PCDS), Diabetes UK, JDRF, TREND-UK, DTN UK, the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists and the Young Diabetologists and Endocrinologists. The result, Language Matters: Language in Diabetes (NHS England, 2018), sets out why language is important and how best to tailor our consultation and use appropriate language.

A valuable guide

As members of the PCDS, we have a responsibility to ensure we and our colleagues who care for people living with diabetes use the appropriate language to engender a sense of collaboration and person-centred approach, rather than one based on guilt and failure extrapolated from numbers and figures on a sheet. Language Matters is a valuable guide that all PCDS members should read, and we should encourage our colleagues to do likewise.

Language Matters dissuades you from using terminology that causes the person to feel judged or guilty. The feelings such terminology evokes mean people with diabetes are less likely to feel part of the consultation, may disengage at a professional and personal level, and thus develop inappropriate health-seeking behaviour. This will adversely affect outcomes for them and their families.

Examples of poor communication abound in Language Matters, as do more suitable alternatives (see Table 1). Do not define someone by their condition by calling them “diabetic” or a “diabetes patient”. Instead, use “person living with diabetes”. Avoid calling someone “non-compliant” or saying they have “failed”, as these terms make the person living with diabetes feel ashamed and a failure. Instead, use the term “was unable to”. Beware of using words such as “control”, as diabetes does not occur in isolation and numerous factors play a part. We, as healthcare professionals, need to realise the burden this word places on the person with diabetes. Use terminology and language that show empathy and understanding.

Non-verbal communication can also lead to disengagement. Examples include not focusing on the person in front of you or not showing active listening skills but focusing on data or the computer screen rather than the person.

A final word

Diabetes care is rapidly changing. We need to build relationships with and demonstrate respect for people with diabetes by placing them at the centre of change and acting as trusted guides throughout their diabetes journey.

Risk ratios of 1.25 for autism spectrum disorder and 1.30 for ADHD observed in offspring of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy.

18 Jun 2025