Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age. Characterised by insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia, it is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. It is further linked to pregnancy-related complications, including gestational diabetes and venous thromboembolism. The disease is distinguished by the presence and degree of three major features: irregular menstruation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovarian morphology (including increased follicle numbers and enlarged ovaries).1 PCOS is a life-long problem. However, the symptoms can be successfully managed with proper medication and lifestyle interventions.

Prevalence

The prevalence of PCOS is known to be around 5–20%, depending on the varying definitions used, and may differ according to ethnic background; it is less common in Black women and slightly more common in South Asian women.2

Ovulatory dysfunction (irregular menstruation), hirsutism, biochemical hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovarian morphology have been observed in 12%, 13%, 11% and 28% of women, respectively.3

When to suspect PCOS4

Clinicians need to be alert to the possibility of PCOS, as up to 70% of women with the condition are known to remain undiagnosed.5

In adults

The diagnosis should be considered if a woman has one or more clinical features of:

- Infrequent or no ovulation (e.g. infertility, oligomenorrhoea, amenorrhoea).

- Hyperandrogenism (which may present as hirsutism and acne vulgaris occurring after adolescence).

In adolescents

Consider if there are signs and symptoms of hyperandrogenism and irregular menstrual cycles:

- Primary amenorrhoea by age 15 years, or

- More than 3 years of irregular cycles following the onset of breast development.

Also suspect PCOS if there is:

- Family history of PCOS, or

- Indirect evidence of insulin resistance (e.g. obesity – especially central obesity – or acanthosis nigricans).

A conclusive PCOS diagnosis cannot be made without the concurrent existence of both menstrual irregularity and hyperandrogenism.

It is also essential to acknowledge an “at-risk” category, who will require follow-up with further age-specific assessment for PCOS, as a means to avoid over- or under-diagnosis of young women.4,6

Managing adolescents who are deemed “at risk” but are not yet diagnosed with PCOS4

In adolescents who are deemed to be at risk but not yet diagnosed with PCOS, including those with PCOS features before combined oral contraceptive pill (COC) commencement, those with persisting features and those with significant weight gain in adolescence:

● Consider prescribing a COC for management of clinical hyperandrogenism and irregular menstrual cycles, provided there are no contraindications.

● Reassess at or before full reproductive maturity (i.e. 8 years post-menarche).

- This will require withdrawing the COC for 3 months or longer to determine the persistence of hyperandrogenic anovulation, and should be accompanied by contraceptive counselling.

● A multidisciplinary team approach is often necessary: consider gynaecologist, sex therapist, dietitian.

● Referral criteria:

- Serum testosterone >5 nmol/L.

- Infertility.

- Rapid onset of hirsutism.

- Glucose intolerance/diabetes (or refer to primary care diabetes team).

- Amenorrhoea >6 months – for pelvic ultrasound to exclude endometrial hyperplasia; if present, refer for endometrial sampling.

- Refractory symptoms.

Confirming the diagnosis4

The diagnosis can be made if two out of three of the following criteria hold and other causes of menstrual disturbance and hyperandrogenisation have been excluded:

● Infrequent or anovulation (usually shows as infrequent or no menstruation).

● Clinical (e.g. hirsutism, acne) or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenisation (check hormone levels; see Box 1).

● Polycystic ovaries on ultrasonography.

Exclude other causes of oligomenorrhoea and amenorrhoea (premature ovarian failure, hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinaemia):

● Luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH): Increased in women with premature ovarian failure, and decreased in women with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

- LH:FSH ratios are often raised (>2.5) in samples collected on days 1–5 of the menstrual cycle in women with PCOS but can be normal.

● Prolactin (normal range <500 mU/L): May be mildly elevated in women with PCOS.

● Thyroid-stimulating hormone (normal range 0.4–4.5 mU/L).

Refer adults, but not adolescents, for ultrasound to identify polycystic ovaries:

● Defined as the presence of 12 or more follicles in at least one ovary (measuring 2–9 mm diameter) or increased ovarian volume (>10 cm3).

● Polycystic ovaries do not have to be present to make the diagnosis of PCOS, and the finding of polycystic ovaries does not alone establish the diagnosis.

Exclude other causes of hyperandrogenism (such as late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome or an androgen-secreting tumour) if:

● There are signs of virilisation (e.g. deep voice, reduced breast size, increased muscle bulk, clitoral hypertrophy).

● There is rapidly progressing hirsutism (less than 1 year between hirsutism being noticed and seeking medical advice).

● The total testosterone level is significantly elevated (>5 nmol/L or more than twice the upper limit of normal reference range).

Complications of PCOS4

PCOS is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, type 2 diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), pregnancy-linked complications, gestational diabetes, venous thromboembolism and endometrial cancer.7

IGT/Type 2 diabetes

Because insulin resistance is the driving factor of hyperglycaemia, women with PCOS are particularly at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. The estimated prevalence of IGT and type 2 diabetes is 31–37% and 7.5–10.0%, respectively, in women with PCOS.8

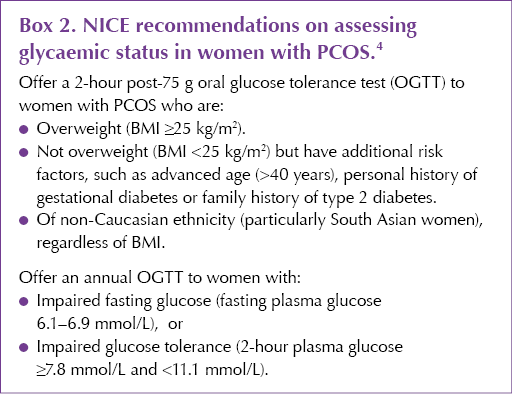

Evaluation of the glycaemic status of women with PCOS (HbA1c, fasting glucose or oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT]) is recommended every 1–3 years, depending on the presence of other diabetes risk factors, as well as at diagnosis.9 NICE recommends the investigations listed in Box 2.4

The RCOG recommends all women with a BMI >30 kg/m2 or a strong family history of type 2 diabetes are offered an OGTT.10 In primary care, if HbA1c is in the prediabetes range (42–47 mmol/mol), an OGTT is indicated.

There is no consensus on who should be referred for consideration of insulin-sensitising drugs (e.g. metformin), and these should not be initiated in primary care. Consider referring to a specialist if there is:

- Severe oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea.

- Impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose.

- Low SHBG levels (surrogate marker for insulin resistance).

Dyslipidaemia and hypertension

Dyslipidaemia is a recurring cardiovascular risk factor, occurring in approximately 70% of women with PCOS.11 Therefore, the latest guidelines suggest women of all ages should undertake a fasting lipid profile at PCOS diagnosis, as well as blood pressure measurement at least annually (depending on cardiovascular risk), together with regular monitoring of body weight.9

Fertility-related complications

PCOS comes with life-long repercussions for women. Gestational complications associated with PCOS are gradually being recognised, some of which include pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension and even miscarriage.

Screening for gestational diabetes and hypertension in women with PCOS (pre-conception and antenatal) is advisable.

Endometrial cancer

Risk of endometrial cancer has been shown to rise by 2–6 times in women with PCOS.12 This may be attributed to the anovulatory cycles where the endometrium is exposed to a continuous flux of oestrogen, unopposed by progestogen, leading to endometrial hyperplasia.

Obstructive sleep apnoea

A positive correlation between PCOS and obstructive sleep apnoea has been demonstrated through several systematic reviews and meta-analyses.13

Management of PCOS: Key messages

The aim of management is to reduce morbidity and complications.

● Inform women diagnosed with PCOS about the possible long-term complications of the condition, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

● Calculate QRISK.

● Encourage a healthy lifestyle (Mediterranean diet, exercise daily and smoking cessation) to reduce the risk of these complications and to help improve the clinical features of PCOS, including oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea, acne, hirsutism and infertility.

● Consider use of:

- Combined oral contraceptive pill for acne, hirsutism, menstrual disturbance.

- Cyclical use of progestogens, or use of levonorgestrol intrauterine device, for amenorrhoea.

- Consider possible use of metformin (with specialist advice).

● For women who are overweight or obese, offer advice on weight loss or consider referral to a dietitian. Explain that weight loss may:

- Reduce hyperinsulinism and hyperandrogenism.

- Reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

- Improve menstrual regularity.

- Improve the chance of pregnancy (if this is desired).

● Follow-up and monitoring on an annual basis: HbA1c (and, if above 42 mmol/mol, arrange OGTT), testosterone, SHBG, weight, blood pressure, lipids.

Resources

● RCOG: Patient information leaflet

● NHS: Polycystic ovary syndrome

● Support groups for people with PCOS include:

Daily oral GLP-1 receptor agonist in development results in significant weight loss but with no dosing requirements.

24 Sep 2025