Type 1 diabetes can occur at any age, from babies and toddlers up to old age. The peak age of diagnosis is around 10–14 years but it is often forgotten that there is another smaller peak at around 40 years of age (Hanas, 2006). The onset is usually rapid, taking family, carers and even healthcare professionals by surprise, and around 25% of children with type 1 diabetes will present with diabetic ketoacidois (DKA) (Sundaram et al, 2009) – a figure that has remained unchanged over the past decade.

Surprisingly, one in three newly diagnosed children will have been seen by a healthcare professional with symptoms suggestive of diabetes in the weeks prior to diagnosis, which suggests that GPs and nurses may be missing opportunities to diagnose type 1 diabetes at an earlier stage, which could possibly avoid DKA (Sundaram et al, 2009). This is important as 80% of deaths in newly diagnosed people with type 1 diabetes under the age of 20 in the UK are related to DKA (Roche et al, 2005). So, what could be done differently?

How common is type 1 diabetes?

The prevalence of type 1 diabetes is about 0.4% and is one tenth as common as type 2 diabetes. However, the incidence of type 1 diabetes is increasing by about 4% per year in the UK in line with other northern European countries. It is less common in southern European countries. In the UK there are about 26 new cases of type 1 diabetes per 100 000 population per year so a full-time GP might expect to see a new case of type 1 diabetes every 2 years (Ali et al, 2011).

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes

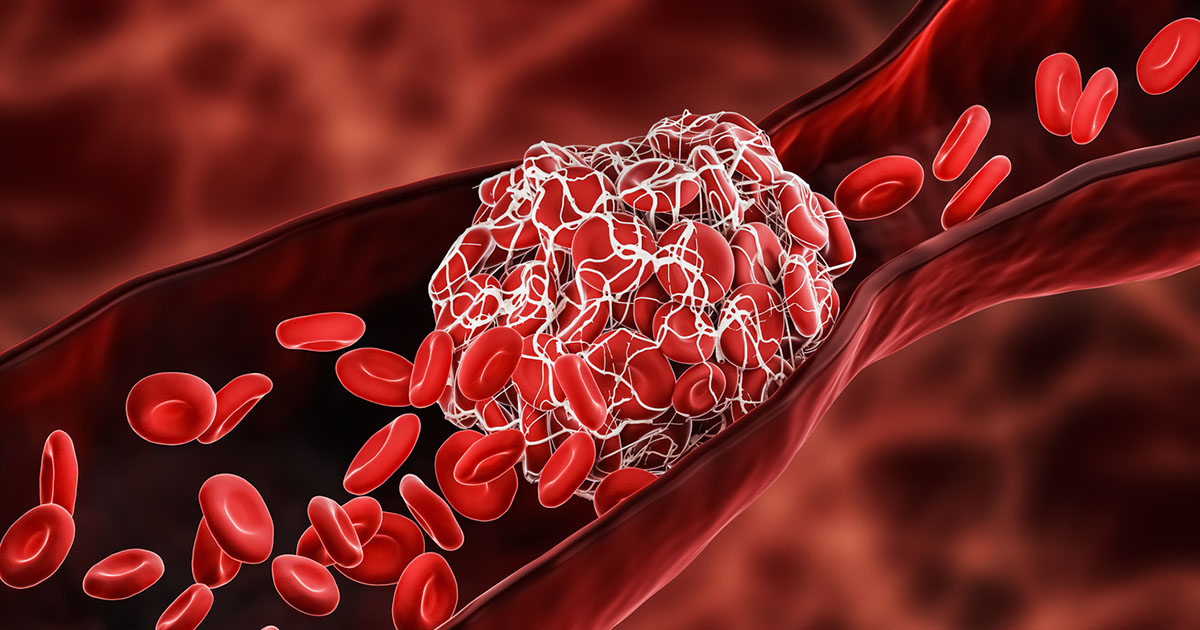

With the flood of type 2 diabetes impacting so much on primary care, it is important to remember that type 1 diabetes is a very different condition. Type 1 diabetes is caused by the complete destruction of pancreatic beta-cells by an autoimmune process, which leads to the inability to produce any insulin. The classic symptoms of polyuria (which is the osmotic result of high blood glucose), consequent thirst and tiredness are a direct consequence of this lack of insulin which, in turn, leads to ketone production and DKA.

Opportunities for early diagnosis

Although a list of symptoms (Box 1) sounds pretty obvious, many of these individually are non-specific and occur in children with acute and self-limiting conditions, and nocturnal enuresis or increased daytime urination may not be mentioned at all by parents. Abdominal pain and vomiting might be put down to gastroenteritis or appendicitis; genital itching or thrush might be treated as a simple infection and weight loss and poor concentration to psychological or social issues. Heavy rapid breathing has been misdiagnosed as asthma or a chest infection.

It is therefore important to think of type 1 diabetes when any of the symptoms in Box 1 occur, and confirmation with either a urine dip test or a random capillary glucose test using a calibrated glucometer should be done immediately – not the following day – and any level of glycosuria or a random capillary glucose level over 7.8 mmol/L would justify a same-day referral (NICE, 2004). Unlike with type 2 diabetes, clinicians should never wait for, or rely on, the results of an HbA1c test.

Small increases in three lifestyle behaviours is effective in reducing all-cause mortality.

27 May 2025