The rise of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors appears to be inexorable. Seminal studies have demonstrated significant reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events with empagliflozin and canagliflozin, reductions in major adverse renal events with canagliflozin and dapagliflozin, and reductions in cardiovascular death and hospitalisation for HF with dapagliflozin and empagliflozin. Indeed, after the publication of a systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Zelniker et al (2019), the front cover of the Lancet in January 2019 suggested that this meta-analysis “provides compelling evidence that [SGLT2 inhibitors] should now be considered as first-line therapy after metformin in most people with type 2 diabetes.”

However, as always, we need to balance these compelling benefits against any potential adverse effects or harms. Once such potential harm is an increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) with SGLT2 inhibitors both in people with type 1 diabetes and in those with type 2 diabetes. In the UK, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin and ertugliflozin are licensed for use in people living with type 2 diabetes, whereas only dapagliflozin is licensed for use in those with type 1 diabetes.

The present BMJ article reviews this association and makes some suggestions on how we can prevent, diagnose and respond to DKA in those taking SGLT2 inhibitors. Symptoms of DKA include excessive thirst, urinary frequency, dehydration, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain and non-specific malaise. DKA is typically characterised by marked hyperglycaemia but, importantly, over a third of individuals with SGLT2 inhibitor-associated DKA have normal or only mildly elevated blood glucose levels (i.e. euglycaemic DKA). Observational studies suggest around a 7-fold increased risk of DKA with SGLT2 inhibitors in people living with type 1 diabetes and a 1.3–8.8-fold increased risk in those with type 2 diabetes. The risk is highest in the first few months of treatment.

A European Medicines Agency (2016) review suggested that DKA was a rare adverse reaction, affecting up to one in 1000 patients, and reassured that the benefits of these medicines continued to outweigh the risks in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. The MHRA (2016) also published a Drug Safety Update warning about the risk of DKA, and this advice is reiterated in the BMJ article.

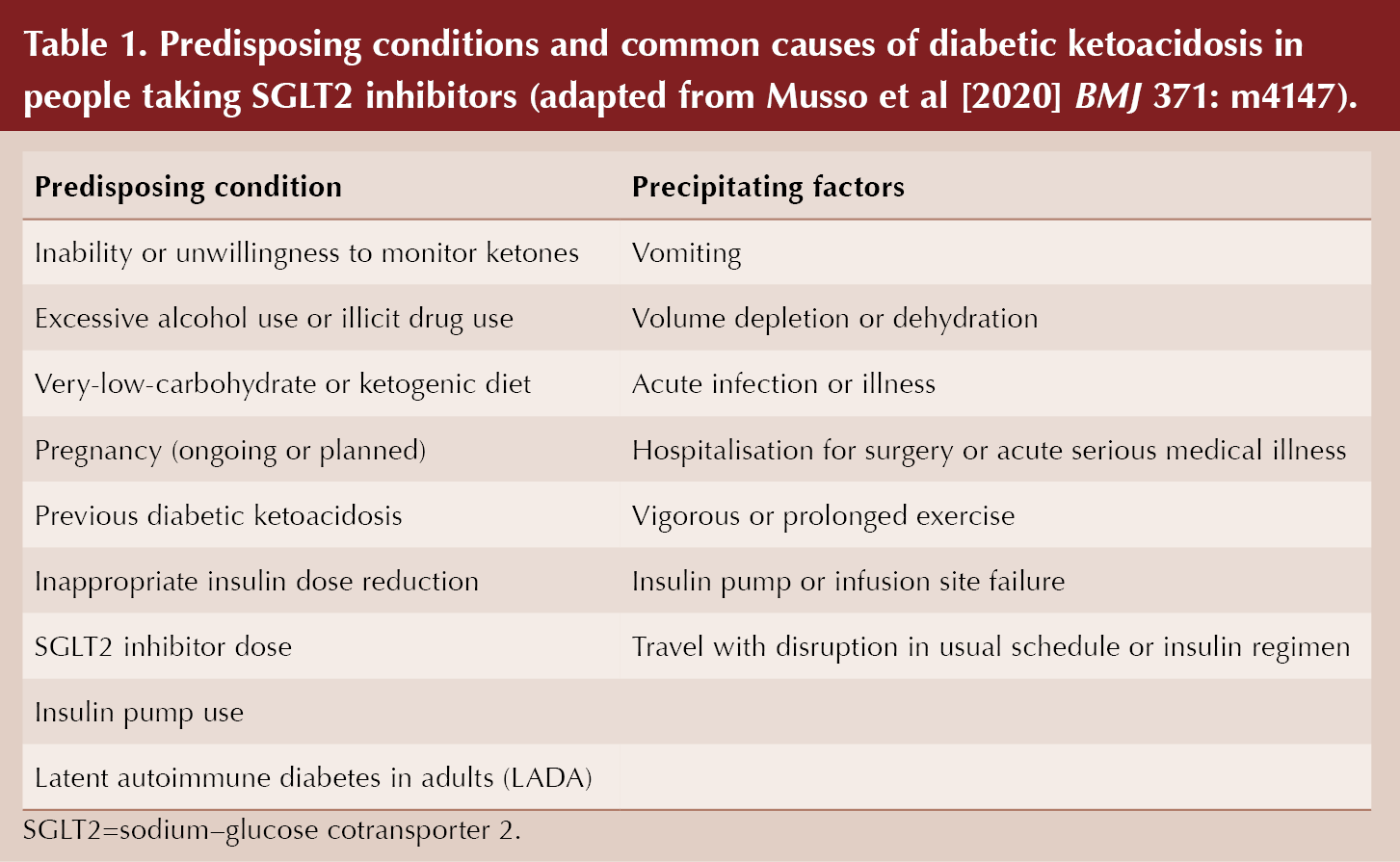

There are certain clinical conditions which predispose to an increased risk of DKA with SGLT2 inhibitors, and over two-thirds of individuals who develop DKA were noted to have at least one of these factors present in observational studies. These were outlined in a useful box within the BMJ article, reproduced in Table 1.

We need to inform patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors of the signs and symptoms of DKA, and advise them to seek immediate medical advice if they develop any. If we suspect DKA, we should discontinue the SGLT2 inhibitor immediately and check for ketones even if blood glucose levels are normal. Blood ketones ≥0.6 mmol/L or ketonuria ++ or higher in urine dipsticks are indicative of an increased risk of DKA, and hospital assessment should be considered. Blood ketone testing is preferable to urine ketone testing as it is more accurate. Importantly, there is no routine requirement to issue ketone testing equipment to those taking SGLT2 inhibitors.

We should not restart SGLT2 inhibitor treatment in anyone who has experienced DKA during use, unless another cause for DKA was identified and resolved.

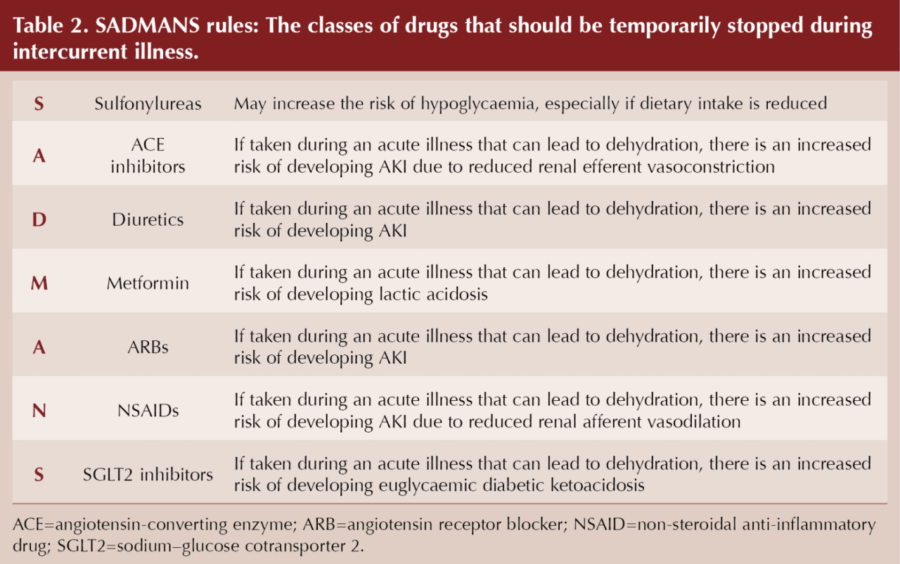

To prevent DKA in those taking SGLT2 inhibitors, we need to discuss sick day guidance and temporarily pause SGLT2 inhibitor treatment in individuals who are hospitalised for major surgery or during any acute serious dehydrating illnesses. Treatment should be restarted once the patient’s condition has stabilised and they are eating and drinking normally.

A useful mnemonic, SADMANS, was originally coined by Diabetes Canada as an aide-mémoire of drugs to temporarily pause during sick days (Table 2).

In conclusion, the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors continue to outweigh the potential risks; however, no drug is without harm and we need to be aware of the potential adverse event of DKA with SGLT2 inhibitors, and to discuss sick day guidance in primary care to prevent the development of potentially fatal DKA.

Click here to view the article in full.

Risk ratios of 1.25 for autism spectrum disorder and 1.30 for ADHD observed in offspring of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy.

18 Jun 2025