Management of older people with diabetes needs to be individualised to take into consideration multimorbidity, frailty status and age-related changes in physiology, as well as the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of diabetes drugs. There is an increased risk of harm, affecting both quality and quantity of life, if these factors are not appraised.

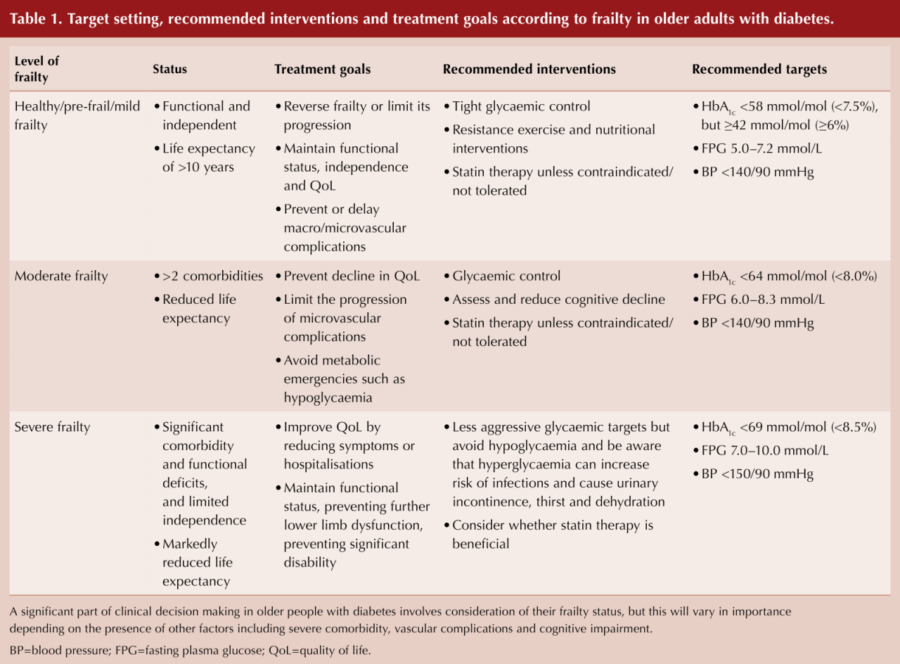

Strain and colleagues (2018) published a UK national collaborative stakeholder initiative proposing the introduction of a frailty assessment scheme as part of routine diabetes management to facilitate more appropriate and safer treatment strategies for the older person with diabetes. Additionally, guidance was provided on individualised glycaemic treatment targets for both intensification and deintensification of therapies to improve the quality of life of older people with diabetes.

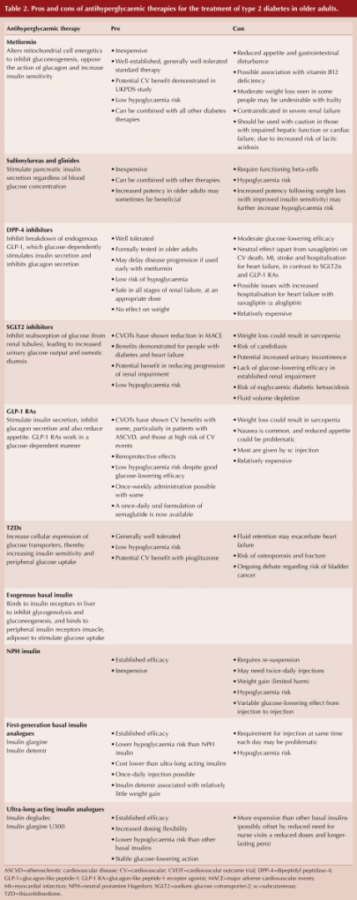

In this recently published expert consensus statement, Strain and colleagues (2021) summarise the relative merits of various drug classes in older people with diabetes, and recommend simple glycaemic management algorithms according to frailty status.

Management of diabetes in the older person should still comprise diet and exercise interventions, as appropriate, as these individuals may also suffer from malnutrition or sarcopenia. Functional deficits can also potentially be reversed with individual activities, such as weight-bearing exercise, aerobic activity or resistance training.

Older frail people living with diabetes and other significant comorbidities, in addition to impaired functional status, are less likely to survive long enough to appreciate the microvascular and macrovascular benefits of longer-term intensive diabetes management (both glycaemic and blood pressure control). These individuals are also at risk of significant harm from adverse effects, such as hypoglycaemia and acute kidney injury. It is, therefore, appropriate to strive for less stringent glycaemic and blood pressure goals and de-escalate therapy, as appropriate.

Within this expert consensus statement is a very helpful table, with recommended treatment goals, interventions and targets according to frailty status (see Table 1).

A further table summarises the pros and cons of currently available anti-diabetes therapies in the UK, with reference to the older person with diabetes (see Table 2).

Of note, whilst metformin is routinely initiated as first-line pharmacological therapy and is generally well-tolerated, we are reminded that it is contraindicated in severe renal impairment when eGFR is <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Metformin should also be used with caution in those with impaired liver function or heart failure, due to an increased risk of lactic acidosis. Hepatic impairment and heart failure are increasingly common with older age, as is declining renal function. The authors suggest checking a baseline eGFR before commencing metformin and then rechecking renal function every 3–6 months thereafter.

Moreover, there is a series of very useful and holistic algorithms within the consensus statement on treatment escalation and de-escalation guidance for the older adult living with type 2 diabetes according to frailty status (mild, moderate and severe; see Figure 1).

Again, we are reminded that over-treatment of older adults is common. An individual over 75 years of age with moderate-to-severe frailty with an HbA1c <53 mmol/mol carries a high risk of hypoglycaemia, and de-escalation of therapies should be considered, especially sulfonylureas or sulfonylurea and insulin combinations. Specifically with regards to insulin therapy, as frailty progresses, older people lose adipose tissue, which reduces insulin resistance and, as a result, much smaller doses of insulin are usually sufficient to provide adequate glycaemic control. Insulin regimens can be de-escalated by simply reducing the dose or switching to alternative regimens with a lower risk of hypoglycaemia (e.g. switching from twice-daily pre-mix insulins to a once-daily basal analogue insulin).

Finally, if a frail older person is found to have an HbA1c <48 mmol/mol, it is reasonable to discontinue all glucose-lowering therapies and simply recheck HbA1c in 3 months with reference to an individualised HbA1c target. Rebound hyperglycaemia can be observed after cessation of therapies, so it is important to ensure that the frail individual remains under review after any de-escalation of therapies. If significant rebound hyperglycaemia is observed after stopping a sulfonylurea, it may be prudent to restart it at a lower dose. Notably, frailty is potentially reversible and can be improved by minimising harmful side-effects, such as hypoglycaemia and excess weight loss secondary to chronic hyperglycaemia.

Click here to read the full statement.

The tables and figure are reproduced under the article’s Creative Commons licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Jane Diggle examines the draft update to the NICE NG28 clinical guideline, plus new advice regarding the discontinuation of Levemir.

10 Sep 2025