A person who is defined as frail is at high risk of adverse outcomes such as falls, immobility, delirium, incontinence, medication side effects, and admission to hospital or the need for long-term care (NHS England, 2024). Managing type 2 diabetes in older adults, particularly those with frailty, presents unique challenges. Current clinical guidelines such as NICE (2022) NG28 emphasise the benefits of tight glycaemic and blood pressure (BP) control, but there is acknowledgement that these standardised targets may not be appropriate for frail, older individuals.

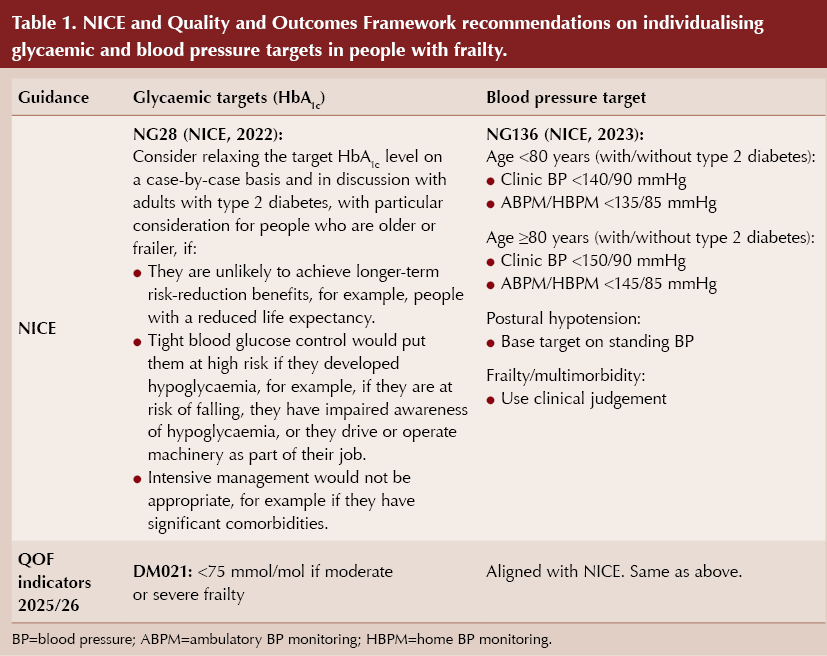

NICE (2022) now recommends an individualised approach to diabetes management for older people, particularly those at risk of hypoglycaemia, those with reduced life expectancy and those who are on polypharmacy. Tight HbA1c targets below 58 mmol/mol (7.5%) are increasingly seen as being potentially harmful in the frail population, and less stringent BP targets (<145/90 mmHg) are being advocated for patients aged 80 years and above (Table 1) (NICE, 2022; NICE, 2023).

Overtreatment of older, frail individuals with type 2 diabetes could increase the risk of adverse outcomes, including hypoglycaemia, falls and hospital admissions related to polypharmacy. Therefore, reviewing the appropriateness of current treatment targets in frail older patients may reduce unnecessary harm, improve safety and enhance quality of life (Strain et al, 2021).

Coding of frailty was a new process stipulated in Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire West ICB guidance in October/November 2024. The overall aim of this quality improvement project at Observatory Medical Practice in Oxford was to assess whether frailty was being coded and whether glycaemic and BP targets for frail, older people with type 2 diabetes were appropriately individualised, and to explore the feasibility of adjusting treatment to reduce potential harms from overtreatment.

Objectives

The primary objectives of this audit were:

- To ensure all people with type 2 diabetes were assessed and coded for frailty.

- To assess whether individualised HbA1c targets had been set for older patients with type 2 diabetes who are frail, through review of medical records and annual diabetes reviews, based on patient factors such as comorbidities, renal function, life expectancy and risk of hypoglycaemia, and using shared decision-making.

Secondary objectives were:

- To assess whether BP and cholesterol targets were individualised in the same population.

- To evaluate whether older people with type 2 diabetes were on appropriate glucose-lowering medications, with particular regard to risk of hypoglycaemia.

- To explore the impact of tight glycaemic and BP control on hospital admissions related to hypoglycaemia, falls and polypharmacy.

- To determine the potential for deprescribing treatment in patients who may be overtreated, and to assess the resources used in managing these patients.

Methodology

People with type 2 diabetes who were coded as Moderately or Severely frail, using a Rockwood Frailty Score of 6 and above (Rockwood et al, 2005), were included in the audit. Those without a recorded frailty score and those with type 1 diabetes were excluded.

Clinical data from November 2024 to April 2025 were collected, comprising the following:

- Individualised HbA1c targets (if the person had one), by reviewing patient records and at annual reviews.

- BP and cholesterol targets.

- Number of BP-lowering medications prescribed.

- Any prescription of glucose-lowering agents associated with hypoglycaemia risk (e.g. insulin, sulfonylureas).

- Hospital admissions related to falls, hypoglycaemia or polypharmacy.

- The presence of comorbidities, renal impairment and life expectancy, which may have influenced treatment decisions.

Key metrics comprised the following:

- The proportion of individuals whose treatment was in line with their individualised targets for HbA1c, BP and lipid management (triple target).

- The proportion of individuals on medications with hypoglycaemia risk.

- Hospital admission rates due to falls, hypoglycaemia or polypharmacy.

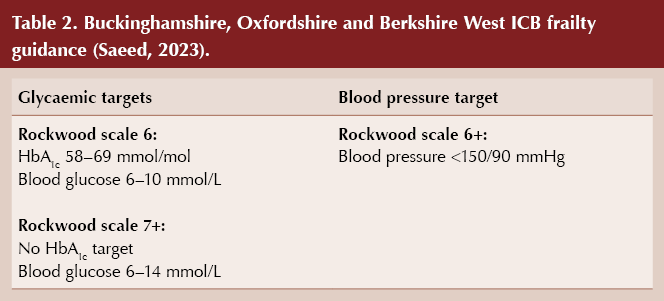

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics, and comparisons were made with current Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) indicators and National Diabetes Audit targets. Results were benchmarked against current ICB guidance on the management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes for people with frailty (Table 2) (Saeed, 2023).

The feasibility of individualised treatment targets was also assessed, including whether there were significant barriers to implementing such targets.

Interventions

Patients were assessed for the possibility of adjusting treatment to individualise their targets more appropriately. Shared decision-making was encouraged to assess individuals’ preferences, functional status and comorbidities. Any potential treatment deprescribing or adjustment (e.g. reducing BP medications or glucose-lowering agents) were explored based on individual needs.

Results

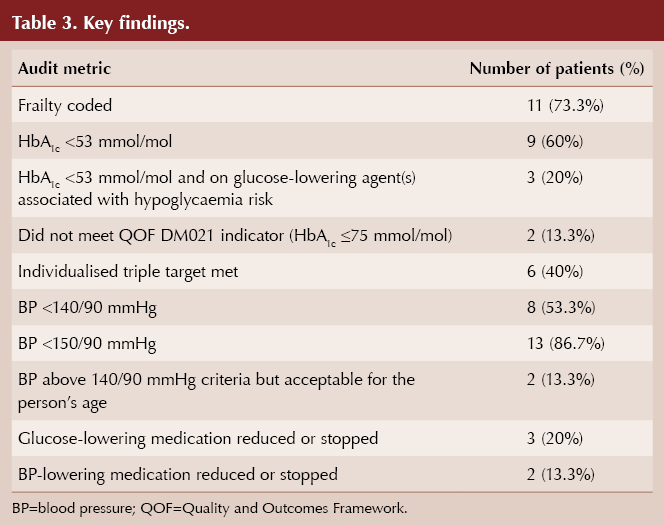

A total of 15 people with type 2 diabetes and a Rockwell Frailty Score of ≥6 were identified. Key findings are summarised in Table 3.

Glycaemic control

In this audit, nine of 15 people (60%) had an HbA1c below 53 mmol/mol, suggesting that a significant proportion may have been managed too tightly. In particular, three of these individuals were being prescribed glucose-lowering agents associated with hypoglycaemia risk.

Two people (13.3%) did not meet the QOF DM021 target of ≤75 mmol/mol, which highlights a gap in achieving standardised diabetes management. One person did not have a glycaemic target recorded, indicating either incomplete documentation or a lack of individualised care planning.

Blood pressure control

Eight people (53.3%) were meeting the BP target of <140/90 mmHg. However, one of these people (6.7%) exhibited postural hypotension, raising concerns about the risks associated with tight BP control in frail populations.

Two people (13.3%) had BP readings exceeding 150/90 mmHg, but these were acceptable per age-specific NICE guidelines, which recommends flexibility in target-setting when appropriate.

Triple target

Only six people (40%) were meeting their composite individualised triple target of glycaemic, BP and lipid management control, indicating a potential need to balance glycaemic control with other clinical priorities.

Medication deprescribing

Glucose-lowering medications were reduced or stopped in three people (20%), including dose reductions of gliclazide and insulin, two agents associated with hypoglycaemia risk.

BP-lowering medications were reduced or stopped in two people (13.3%), aligning with the effort to reduce overtreatment and potential harm. Although these individuals did not complain of postural hypotension, their BP was excessively low (<120/80 mmHg).

Discussion

In this audit, frailty was appropriately coded in 11 of 15 patients (73.3%). This is a positive indicator; however, the fact that 26.7% of patients were not coded appropriately indicates a potential gap and inconsistency in holistic assessment and treatment. Achieving near-complete coding would better support individualised care.

This audit highlights the complexity of managing type 2 diabetes in older, frail adults and underscores the importance of individualised care. Overall, 60% of patients had an HbA1c <53 mmol/mol, indicating that a significant proportion may have been managed too strictly. Although achieving tighter control is beneficial in terms of long-term outcomes, this may not align with the individualised approach recommended for frail older adults, in whom the risk of hypoglycaemia and adverse events outweighs the benefits of stringent control, particularly given that three of these patients were on glucose-lowering agents associated with hypoglycaemia risk (e.g. insulin, sulfonylureas).

Local ICB guidelines recommend flexibility in BP targets, particularly for patients aged ≥80 years, in whom targets up to 150/90 mmHg are considered reasonable (Saeed, 2023). This audit reflects some adherence to this guidance, with eight people having a BP under 140/90 mmHg but most having a BP under 150/90 mmHg. Only two people had elevated BP (>150/90 mmHg), but one of these patients was very severely frail (Rockwood scale 8), a renal patient nearing end of life, so clinical judgment would suggest that the person’s BP of 165/80 mmHg was acceptable. The second patient, moderately frail (Rockwood score 6), had a BP of 154/80 mmHg which can also be viewed as acceptable since they were experiencing dizziness on standing (postural hypotension).

Local ICB guidance promotes actively reducing hypoglycaemia risk and polypharmacy where possible. While the audit shows some progress in this (a reduction in glucose-lowering medications in 20% of the cohort), the low rates of medication deprescribing suggest a potential over-reliance on aggressive treatment despite recognised risks in the frail elderly population. Further emphasis on deprescribing may be needed.

Comparing the findings with current guidelines, including QOF, NICE and local ICB recommendations, it is evident that individualised target setting is feasible but not yet fully implemented. Barriers identified include incomplete documentation, clinical inertia, risk management concerns, and limited use of shared decision-making. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach involving improved record-keeping, enhanced clinical decision support, and more robust training in personalised care strategies.

By fostering a more patient-centred approach that emphasises quality of life and safety over strict metabolic control, healthcare teams can better align treatment strategies with the unique needs of older, frail adults with type 2 diabetes. Further efforts should focus on embedding individualised target-setting into routine practice, enhancing documentation processes and actively involving patients in treatment decisions.

Managing type 2 diabetes in older adults is complex due to the presence of multiple comorbidities, reduced life expectancy and increased susceptibility to adverse treatment effects. This population is at higher risk of hypoglycaemia and its serious consequences, such as falls, fractures, hospital admissions, cardiovascular events, and mortality. Therefore, evaluating frailty should be a standard part of diabetes assessments in older individuals, and both glycaemic goals and treatment plans should be adjusted accordingly (Strain et al, 2021).

Frailty should be re-evaluated following each intervention, keeping in mind that it is a dynamic condition that can potentially improve if hypoglycaemia and its associated effects are addressed and resolved (Strain et al, 2021). Creating individualised care plans (through existing proformas or by devising new ones); assessing frailty after each intervention in primary care; and offering regular structured medication reviews, assessing falls risk and deprescribing may address current concerns with safety and overtreatment of frail, older adults.

Recommendations

Enhance documentation: Establish protocols to ensure that individualised targets and frailty assessments are consistently recorded.

Strengthen decision-making frameworks: Develop tools to guide clinicians in balancing tight control with patient safety, particularly for those on hypoglycaemia-inducing medications. For example, there could be an Ardens template for older, frail adults with type 2 diabetes with a methodical approach at deprescribing; alternatively, an in-built EMIS document, which creates an individualised care plan for this cohort of patients only, could be used.

Increase focus on deprescribing: Regularly review medication regimens to identify opportunities for safely reducing treatment intensity. These patients could be reviewed every 3–6 months rather than annually.

Training and education: Provide ongoing education for healthcare professionals on the principles of individualised care in frail older adults. Create a standard operating procedure or guideline outlining this. Update local ICB guidelines to include targets (e.g. HbA1c 58–75 mmol/mol) for those patients with a Rockwood score of ≥7. All patients/carers should be educated about risk, recognition and treatment of hypoglycaemia.

Person-centred approaches: Implement shared decision-making tools to align treatment goals with patient preferences, focusing on quality of life rather than strict adherence to traditional targets. Obtain patient/carer feedback after completing the first phase of the project.

Structured medication reviews (SMRs): Older adults with moderate or severe frailty should be allocated a diary recall for SMRs at either annual or 6-monthly intervals, depending on their frailty assessment.

Coding and reassessment of frailty: Code at each intervention in primary care and recalculate the individual’s risk of falls.

Re-audit: Re-audit annually or 6-monthly at SMR appointment and review glucose-lowering agents and HbA1c levels, and assess falls risk through anticholinergic cognitive burden (ACB) score.

The Roger Gadsby Award

This project was awarded the Roger Gadsby prize recognising an outstanding audit in diabetes primary care at the 2025 National Conference of the PCDO Society, and has subsequently been written up for publication in the journal.

Submissions for the 2026 Award will open later this year.

Acknowledgement

Amara Aziz thanks Professor Naresh Kanumilli for facilitating the commissioning of this article.

Why is shared decision-making important, what barriers are there and what tools can support it?

28 Jan 2026