There is growing concern about the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) in children and adolescents (Kaufman, 2002; Hannon et al, 2005; Dea, 2011; Praveen et al, 2015). It is thought that the rise in childhood obesity is a significant contributing factor (Kaufman, 2002; Hannon et al, 2005; Dea, 2011). Other risk factors include female sex (Pinhas-Hamiel and Zeitler, 2007; Khanolkar et al, 2016), having a first-degree relative with T2D (Dea, 2011) and – in the UK – South Asian ethnicity (Khanolkar et al, 2016). T2D progresses faster in young people (YP) than their adult counterparts (Narasimhan and Weinstock, 2014) and suboptimal management in childhood and adolescence is linked to poorer health outcomes and increased risk of complications, eg cardiovascular problems (Reinehr, 2013; Cahill et al, 2016).

The central aim of T2D interventions in children and young people (CYP) is to maximise time within the target glycaemic range. Interventions include education, medication and lifestyle modification, such as diet and exercise (Pinhas-Hamiel and Zeitler, 2007; Dea, 2011; Ramkumar and Tandon, 2012; Praveen et al, 2015); however, there is limited evidence of the efficacy of these approaches (Copeland et al, 2013; Zeitler et al, 2012).

Despite the importance of managing diabetes well, this very difficult in practice. Living with T2D is challenging emotionally (Huynh et al, 2015) and possible barriers to optimal management in CYP include embarrassment, wanting to be ‘normal’, balancing competing interests and seeking acceptance (Mulvaney et al, 2008; Protudjer et al, 2014). Adolescence is a barrier to adherence and optimal diabetes control, with parents describing adolescents as lacking concern for the future and not taking the risks and complications of their condition seriously (Mulvaney et al, 2006). Environmental factors have been noted, with issues related to socioeconomic status, school environment, food poverty, a lack of resources to make healthy food choices, and siblings without diabetes having an impact on diabetes management (Mulvaney et al, 2006; 2008; Protudjer et al, 2014).

The Children’s Diabetes Team (CDT) at Bradford has noticed a steady increase in CYP with T2D over the past 10 years. Patients are referred to the CDT when high blood glucose levels are identified following admission to hospital for an unrelated complaint. There are 18 CYP with a diagnosis of T2D; this number is predicted to rise and is unlikely to reflect the true prevalence within the local community. Currently all CYP with T2D are from a South Asian background. They often have an immediate family member with T2D. Anecdotally, experience to date suggests there may be multiple barriers to engagement for this group. For example, clinicians have reported that patients with T2D struggle to attend clinic appointments regularly, often forgetting their appointment or prioritising other things such as after-school activities. Clinicians have been concerned that families do not always appear to understand the seriousness of the condition in CYP, which may impact on attendance levels. Patients often present with high HbA1c levels, and appear to struggle to control their diabetes well, with low compliance to metformin and insulin injections.

While improving diabetes control in CYP is essential to improving health outcomes, doing so is complex and may require ‘multimodal interventions to address individual, family and social processes’ (Mulvaney et al, 2008 p675). This pilot study sought to explore how this may be achieved for CYP presenting with T2D in Bradford.

Method

Potential participants were approached through attendance at clinic and/or letters sent outlining the study followed by a telephone call. Participants included YP who attended clinic regularly and those the team had struggled to engage with, so it is hoped their views are representative of the larger sample. YP who did not participate either did not respond to recruitment letters or cited reasons such as being too busy with school work or not wishing to talk about diabetes more than they do in clinic. Two further YP agreed to take part but did not attend on the day or respond to further calls from the lead researcher and were withdrawn from the study.

YP with a diagnosis of T2D and their parent/caregiver were interviewed together using a semi-structured interview. All five YP identified their ethnic group as Asian British, Pakistani background. All were under the care of the CDT in Bradford, were aged between 11 and 16 years and had received their diagnosis over 2 years ago. Four identified as female and one as male.

Participants’ responses were transcribed and analysed qualitatively using thematic analysis to identify key themes, ideas and patterns within the data without the limitations of a pre-existing theoretical framework (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The results were discussed with a diabetes nurse from a South Asian background alongside a member of the hospital Muslim chaplaincy; these discussions were used to inform recommendations. Ethical approval was granted by the local research ethics committee and Health Research Authority.

Findings

Four major themes were identified.

Reaction to diagnosis

Experience of being diagnosed

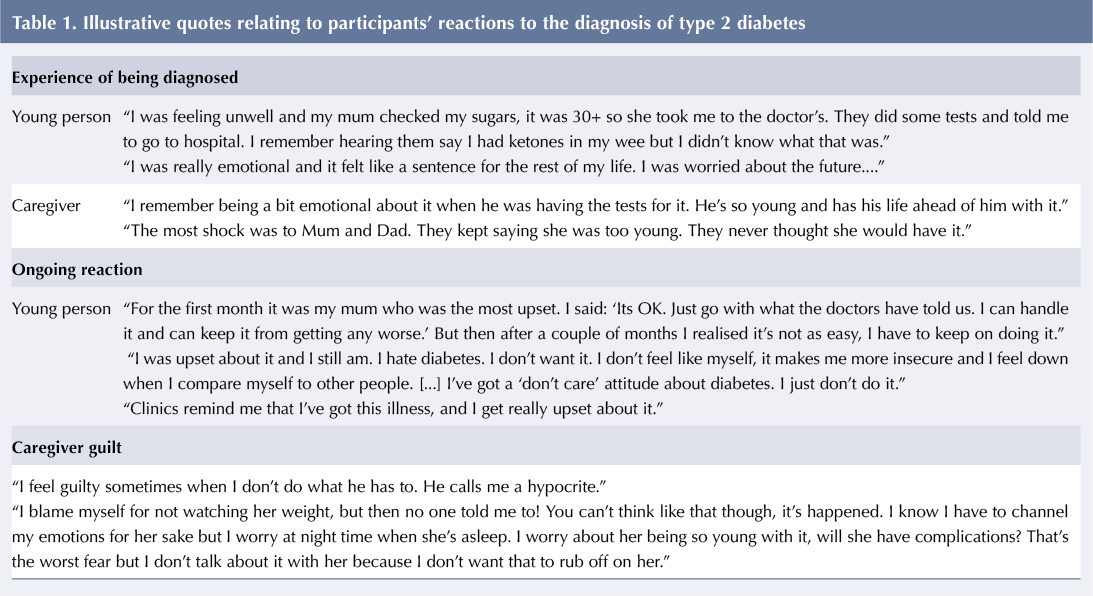

All YP and their caregivers discussed their memories of diagnosis and initial experiences of receiving input from healthcare professionals, see Table 1. Some had experienced uncertainty leading up to diagnosis, whereas for others diagnosis was unexpected. Regardless of their experiences, YP and their caregivers described an emotional response to receiving the news.

Ongoing reaction

The majority discussed the gravity of their diagnosis not ‘sinking in’ for a long time. They described an ongoing emotional reaction with a far-reaching impact on their attitude towards themselves and their treatment, see Table 1. Some YP explained that as a result of how their diagnosis makes them feel, they would rather not think about having T2D and ‘try to be normal’ instead, only acknowledging they have the condition when they are due to attend clinic.

Caregiver guilt

Caregivers expressed some difficult ongoing feelings surrounding the young person’s diagnosis in relation to guilt or blame, see Table 1.

Understanding of diabetes

Participants discussed their understanding of diabetes, which appears to have developed from a number of sources, see Table 2.

Previous family experiences

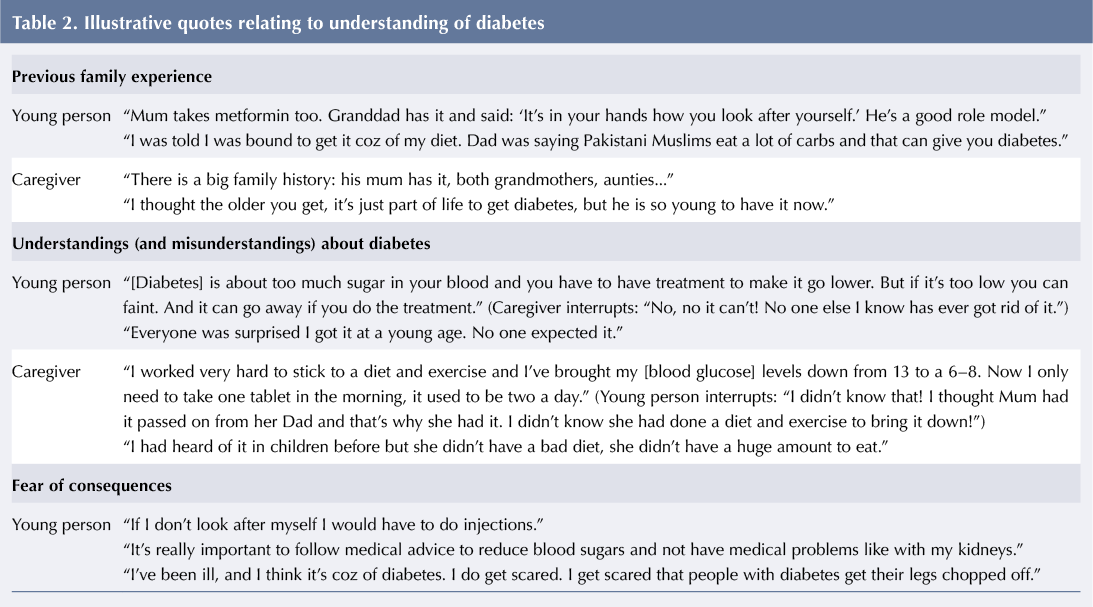

All YP and caregivers discussed having other family members with a diagnosis of T2D. This extended family history at times meant that, although still a shock, families felt like a diagnosis was ‘inevitable’ at some point for the young person.

Understandings (and misunderstandings) about diabetes

Familiarity with the condition meant families had some prior understanding about what having T2D entails, which for some caregivers meant diabetes was seen as “just another thing to get on with”. However, some confusion and inconsistencies between different family members’ understanding about T2D and the aims of treatment emerged during the interviews, suggesting familial experience of T2D has not necessarily improved understanding, or even been discussed previously at home. Despite prior understanding, participants appeared to be less familiar with T2D presenting in YP, often seeing it as an ‘older person’s condition’. They did not discuss any possible differences in how the condition may present, progress or be managed in relation to YP.

Fear of consequences

All participants discussed worries about the consequences of T2D, referring to short- and long-term concerns and fear of complications. While YP discussed ongoing worries about their health, this did not necessarily equate to a change in behaviour; at times it led to inaction, minimising the effect of treatment, or ignoring the diagnosis all together.

Adjustment to living with T2D

What does it mean about me?

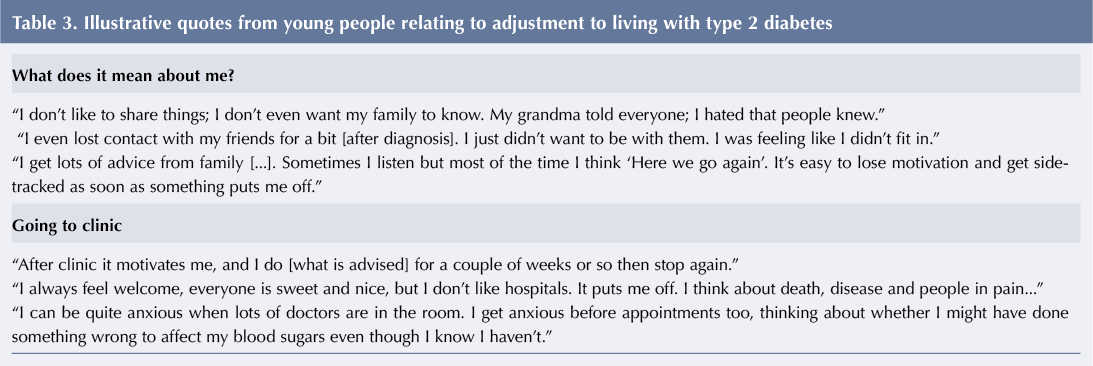

YP appeared to be trying to make sense of their identity in relation to their diagnosis. They discussed feeling ‘different’ and were concerned about being treated differently because of their T2D. Some discussed wanting to hide the fact they had T2D and appeared to feel some shame in relation to their diagnosis, see Table 3.

YP discussed how the diagnosis has affected interactions with their family. Lots of people were giving them advice, whether they asked for it or not. This resulted in them feeling ‘nagged’, which at times affected their behaviour.

Going to clinic

YP and caregivers discussed positive aspects of clinic attendance, such as having the opportunity to gain medical advice, getting ideas for how the family can make changes, and a temporary boost in motivation. However, YP discussed hospital appointments as provoking anxiety at times and being an unwelcome reminder of their condition, see Table 3.

Looking after myself

Following advice

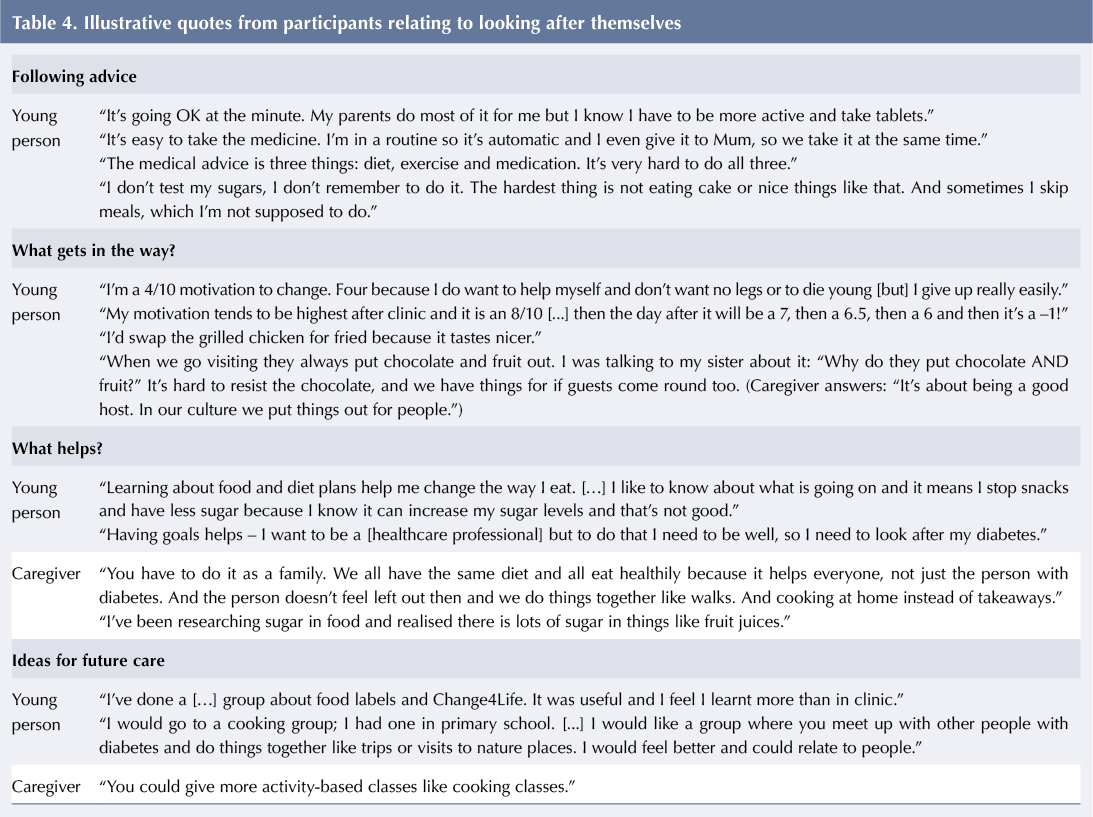

YP tended to discuss what was going well for them in relation to elements of the treatment regimen they were adhering to, see Table 4. However, most spent time discussing aspects of their treatment regimen they were finding difficult to ‘stick’ to and frequently referred to “what I should be doing but don’t”. These discussions enabled participants to explore potential barriers to making changes in line with advice, including their own motivation, the family approach and their immediate environment.

What gets in the way?

YP discussed their motivation to follow advice from healthcare professionals as being ‘short lived’ and referred to struggling to maintain the daily effort required to stick to diets and regular medication. They often referred to this as being a personal fault or flaw, which in turn led them to feel helpless in terms of whether they could make lasting changes. They talked about how food preferences, the environment around them and cultural factors can impact how able they feel to make dietary changes, eg discussing the proximity of fast food outlets to their home and having siblings who freely consume those foods. Families with experience of visiting or living in Pakistan noticed the impact this change in environment can have on health. They attributed changes to the availability of fresh food, the opportunity for exercise and the scarcity of fast food outlets in rural areas, eg: “I went to Pakistan […] for a month and lost loads of weight. People were saying I looked skinny when I got back.”

Further barriers to ‘looking after’ T2D included other aspects of life, such as school (“work takes priority over diabetes”) and where the family locate responsibility for change. When families placed responsibility with the individual with T2D, the young person often felt singled out and blamed for the condition. They discussed finding it difficult to make changes that were not being upheld by other family members.

What helps?

In contrast, when a family-wide approach was used to manage diabetes, YP and caregivers discussed seeing positive results for the whole family, see Table 4. Other factors that appeared to have a positive impact on YP’s ability and confidence to make changes included increasing their understanding of the condition by researching and asking questions themselves, and having goals to focus on in order to have a positive reason for maintaining their health.

Ideas for future care

Participants were asked for ideas about how they might like to receive support from the CDT. Suggestions tended to focus on healthy eating and cooking, and were more practical-based than traditional multidisciplinary team appointments. Although the majority discussed the potential benefits of a group setting, one participant indicated that they would not attend as they would find this too embarrassing.

It appears that, while most participants wished to appear grateful for the service they had received, the benefits of clinic appointments were often seen as short-term and appeared to be short-lived. Findings suggest the focus on patient-only diabetes clinics may need to shift to better suit this group’s needs.

Discussion

This small study has provided further insight into the experience of T2D for YP and their caregivers from a Pakistani background. Findings highlight possible barriers to accessing current healthcare services. Previous research has emphasised the need for parental involvement in improving YP’s ability to manage a long-term health condition (Cahill et al, 2016), however it seems a wider family approach is important for this group. Participants often lived with or had daily contact with extended family. When considering a ‘family approach’ to T2D, it is important to consider who is in the family and people’s expectations and beliefs in the context of their religious and cultural background. Pallan et al (2012) found that within South Asian households where extended family members are present, the grandmother often influences younger family members’ diets and may have different views around food, including seeing overweight children as healthy. Barriers to engaging with advice about weight management may include parental concern that doing so could undermine YP’s emotional wellbeing and lead them to develop eating disorders in later life (British Psychological Society, 2019). Lawton et al (2008) highlighted the importance of consuming certain foods to maintain cultural identity; not eating together or accepting food offered by family or community members can cause offence or alienation in South Asian culture. Many South Asian families require quick energy-rich foods to be consumed once YP have finished school and before attending mosque (Pallan et al, 2012), something commented on in the current study. YP appeared to be aware of some of the complexities surrounding food and eating, recognising there are psychological reasons for eating, eg for comfort when angry or upset, as well as cultural and religious aspects, eg providing sweet food for guests.

YP reported an ongoing adjustment process, in contrast with other research suggesting adjustment to T2D diagnosis gets easier over time (Protudjer et al, 2014). Participants remained aware of their condition and discussed concerns about the long-term health consequences, and feeling anxious, depressed or helpless about their diagnosis. Increased awareness and fear of negative consequences does not necessarily lead to behaviour change (Hood et al, 2015; Kelly and Barker, 2016); participants discussed how fear and anxiety led to them ignoring the consequences of T2D or at times acting against medical advice.

Recommendations

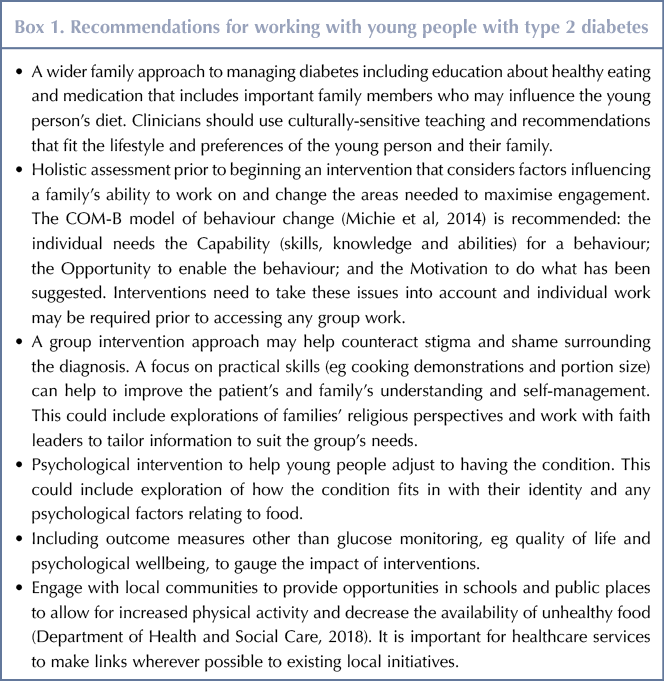

Common recommendations based on the limited research investigating the efficacy of approaches to T2D management in CYP include a combination of medication and lifestyle changes, such as weight management and taking into account psychosocial aspects of living with the condition. Based on the findings of the current study, a number of recommendations can be made for working more effectively with YP with T2D, see Box 1.

Conclusion

This study provides further information about the impact of T2D diagnosis on YP and their families as well as possible barriers to successful management. Continuing to apply a traditional type-1 model of treatment is unlikely to be successful. The recommendations are a useful starting point when considering how to develop services to engage with and meet the needs of this patient group. Additional research with a larger, more heterogeneous population of YP with T2D would contribute further ideas. It is imperative to work in creative and innovative ways to achieve the best possible outcomes.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022