The challenge of living with the demands of diabetes can result in the negative emotional or affective experience known as diabetes distress (Polonsky et al, 1995). Severe diabetes distress affects one in four people with type 1 diabetes, one in five people with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes and one in six people with non-insulin treated type 2 diabetes (Hendrieckx et al, 2019). High levels of distress have been linked to lower levels of self-management, higher HbA1c levels and poorer health outcomes (Fisher et al, 2012; Schmitt et al, 2016; Wardian et al, 2019; Skinner et al, 2020), making it important for diabetes care teams to assess and address it (Speight et al, 2021). However, concerns exist that screening for diabetes distress has been inconsistent in the UK (Wylie et al, 2019).

Aims

This study aimed to explore the acceptability and feasibility of incorporating screening for diabetes distress into diabetes specialist nurse (DSN) clinics.

Methods

Study design

Qualitative interviews were used to capture DSNs’ perceptions of incorporating screening for diabetes distress into their clinics. The interviews were conducted with DSNs across two services providing specialist diabetes care. The project was registered as a service development project with participating NHS trusts and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Oxford Brookes University (ref. no. HLS/2108/AJW/01).

Participants

The DSN teams from outpatient and community services were invited to participate as part of the quality improvement process to develop, implement and evaluate the process of incorporating diabetes distress screening. All nurses participating in the project were invited by a researcher via an email to share their views in an individual interview. Interested nurses were provided with study information by the research team and gave informed consent to participate.

Project details and data collection

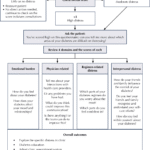

An hour-long training for DSNs by a consultant clinical psychologist covered understanding of the concept of diabetes distress, measuring diabetes distress with the Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS; Polonsky et al, 2005) and interpreting the scores, providing feedback and advice to people with diabetes, and referring to a mental health specialist service. Each nurse was provided with a flowchart detailing the process (Appendix). At the clinic, the nurses were to review and discuss the score for each person with diabetes who completed the DDS.

In the outpatient clinic, people with diabetes were to receive the DDS via the Patient Portal (an online system with patients’ medical records), with nurses receiving the report prior to the consultation. In the community clinic, people with diabetes were to receive the DDS via post with an administrator processing the score and preparing a report for nurses prior to the clinic.

Data collection took place after DSNs completed the training. The training was delivered online in June and July 2021, and interviews took place online in March and April 2022.

Data analysis

Interview data were transcribed verbatim and analysed using qualitative description, since straightforward descriptions of phenomena were needed (Sandelowski, 2000). The analytical process was focused on exploring DSNs’ views of the acceptability and feasibility of incorporating diabetes distress screening into routine clinics.

Results

Six DSNs, three per service, were interviewed. Full implementation of screening using the DDS did not take place as planned for a number of reasons: the Patient Portal was not set up on time (the outpatient service), cases were not possible to follow (the community service), care and service were disrupted due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, the interviews captured the DSNs’ perspectives on the diabetes distress training and the proposed implementation process.

The idea of incorporating the diabetes distress screening into routine nurse-led clinics was broadly supported with some considerations. DSNs acknowledged the importance of addressing the emotional needs of people with diabetes and the benefits of screening for diabetes distress. However, they also raised concerns about the use of the scale in everyday clinical practice.

Benefits of changing how diabetes distress is addressed

While DSNs were familiar with the concept of diabetes distress prior to the intervention, their practices in assessing and monitoring it varied. They would assess emotional distress mainly to confirm or to evidence that a person with diabetes had an elevated level of distress. The DSNs recognised that incorporating the assessment of distress as part of the main assessment might identify people in need of support who would otherwise be missed due to screening being optional, depending on nurses’ judgement, confidence and skills to undertake it.

Probably being used slightly subjectively and randomly and that actually formalising it and bringing it in as part of our core assessment of people was absolutely critical. It’s about trying to find a way that we are giving equity to do that assessment for everybody, which we don’t have currently. [2]

Some DSNs were using generic tools to assess anxiety and depression, but also recognised the benefits of using a tool to specifically assess diabetes emotional distress. A specific tool was seen as being able to provide a greater degree of insight into someone’s management of diabetes, as well as a helpful way of starting conversations about emotional wellbeing.

I liked the fact that it was more specific to people with diabetes, rather than just using the generic screening tools that we all can use. I liked that it seemed to be more specifically based around screening for diabetes specific related distress. [3]

It does make you feel prepared. It does make you know the right questions to ask the patient. It does prompt you on how to respond to the patients as well, yeah. [5]

For some DSNs having the diabetes distress score to hand helped in conversations with people with diabetes and other healthcare professionals. Some thought that quantifying emotional distress helped it be taken seriously by the wider team. Having “a number” was seen as carrying weight in biomedical conversations and making emotional distress difficult to ignore.

I think the beauty is that it comes up with a value that allows you to lead the conversation and possibly guide the – you’ve answered that really objectively at home, let’s see what that means for real. [2]

So, it’s been quite useful to take that to MDTs and stuff. They love a score. The consultants love it if you score. If you can give something a number, they really like it. I think it’s just for an audit to see whether it’s working. They can’t really argue with me if I bring a number. Whereas if you haven’t, it’s just your opinion, isn’t it? [6]

Concerns about screening for diabetes distress

While comments were broadly positive for screening for diabetes distress, DSNs raised concerns related to screening being “a tick-box exercise” and leading to “opening a can of worms”. There was a shared understanding that the tool itself is only useful if embedded in practice, with the score being acted upon.

I think it certainly seems like something that’s important to focus on, but whether the actual tool itself is useful, I don’t know. I think a big barrier to using it is that it almost feels like another tick-box exercise, another thing that we have to tick off that we’ve done at the end of our consultation. [3]

To help embed the screening tool into practice and moving beyond “a tick-box exercise”, DSNs emphasised the importance of providing people with diabetes with the questionnaire beforehand, so that they do not rush when completing it. There was an opinion that its introduction needed to be when the nurse/patient relationship had been established, with patients feeling more comfortable in sharing this aspect of living with diabetes.

So, I think it is a good thing, and I think it is something that definitely needs to be incorporated in whatever format works. But I do think it’s something – and this is what we were trying to achieve, I know, with the study, that they need to have beforehand, so they can have a good look at it, or time beforehand to put some thought into how they want to answer it so that it’s not just tick a lot of boxes quickly and give it back type thing. It’s definitely a gap in our assessment. I think we all admit that. [4]

I’m not sure that we should do it at the very first appointment. I think there’s something about relationship building so that it comes in, but that’s easy to see for nursing. It’s not quite so easy to see for medicine. [2]

Secondly, all DSNs were troubled by the possibility of managing the conversation once diabetes distress was introduced as a topic sometimes referred to as “opening a can of worms”. The DSNs shared concerns about the conversation impacting their limited clinical time, their ability to address other aspects of diabetes care and their ability to appropriately support those who opened about their distress.

I don’t feel I’ve got a good understanding of that and how to help people. So, it almost feels as if well, okay, I’ve got them to fill in this questionnaire and we’ve talked about it and we’ve highlighted a problem, but then how do I help you with that? That feels really uncomfortable for me, there’s that moral injury where you feel like we’ve identified an issue, but I can’t fix it and I don’t know how to help you fix it. [3]

I’d like to feel more confident. I know I probably wouldn’t always be able to, but I’d like to feel more confident. I think sometimes we don’t probe as deeply because we worry that we won’t be able to – we’ll open a can of worms almost and then not be able to actually help with that, sorting that person and finding a route for them. [4]

Some DSNs reflected that there may be value in acknowledging a person’s distress without specifically addressing it, but it was also clear they were unsure how to respond and what to do with information that was shared.

You worry you’re going to open something, almost like opening a wound, open some bad feelings, and then just send them out with no kind of improvement. But then, for some people, actually, just you acknowledging that it’s really hard, living with diabetes is really hard, is perhaps what they need. [4]

Sometimes there are things that you can’t – it’s very hard to – it’s something that’s hard to change, isn’t it? But maybe by acknowledging it and talking about it, that might just help sometimes for people anyway. I didn’t want to say it because it was in the back of my head and I thought it’s almost like opening a can of worms. You think, oh, how do I – what do I actually do with this? [6]

Discussion

There has been a growing recognition of the need to address the emotional needs of people living with diabetes in routine diabetes care. We explored the acceptability and feasibility of incorporating screening for diabetes distress, using the DDS, into routine diabetes care delivered by DSNs. The DSNs were trained to use the DDS and were involved in developing the proposed screening implementation process. Despite this, they expressed concerns about using the DDS to screen in everyday practice, providing valuable lessons to be learnt for future projects aiming to implement diabetes distress screening. These could potentially apply for other mental health screening processes in different conditions.

Interviews with DSNs were broadly supportive of assessing and addressing diabetes distress in clinical practice. They were positive about embedding diabetes distress screening into their clinics. They felt that their routine practice may have missed people needing emotional support due to a lack of universal screening. They identified a number of benefits of routine screening using a standardised tool which scored the level of distress including: i) identifying people in need of support that would be otherwise missed, ii) guiding nurses in undertaking conversations about person’s diabetes distress and iii), and quantifying distress which supported nurses in discussing emotional distress with other clinicians.

However, the DSNs in the present study had two main concerns about screening. First, they feared the screening would become a “tick box exercise” if not well managed. They highlighted that both people with diabetes and DSNs need time to engage with the screening questionnaires and act on elevated distress scores. Secondly, they worried about managing conversations with patients about their distress – referred to as “opening a can of worms” by some, and were concerned that they would not be able to support patients adequately. DSNs debated the morality of acknowledging someone’s distress if they felt they could not offer any support, illustrating the burden for nurses trying to deliver the best care for people with diabetes. It may be reassuring to some clinicians that the Diabetes UK guide for healthcare professionals on diabetes and emotional health (Hendrieckx et al, 2019) encourages conversations about how diabetes impacts emotional health; being listened to and having one’s feelings around living with diabetes acknowledged, is seen as having a positive impact on those who are experiencing distress. Furthermore, the recent survey done by the International Diabetes Federation (2024) indicated that 3 in 4 people living with diabetes are seeking increased support for their emotional and mental well-being from their healthcare providers. Further research into the perspectives of people with diabetes on diabetes distress screening is needed to explore the nurses’ perceived dilemma of whether distress should be acknowledged even if there are not practical avenues of support available.

DSNs’ concerns reported in the present study extend and somewhat contrast with the findings of fourteen studies across the two reviews that suggest clinicians’ lack of time to screen and lack of understanding of the rationale and benefits were the main barriers to routine diabetes distress screening (McGrath et al, 2021; Nhlabatsi et al, 2024). The present study illustrates that the complexities of screening for distress in diabetes clinics may have been oversimplified by attributing the responsibility for difficulties around integrating diabetes screening into routine care to individuals. In the present study, nurses’ concerns were linked to their previous experiences with screening for emotional distress, their own preparedness to talk about and manage emotional distress, strategies of coping with distress and unresolved issues, confidence in using the screening tool, and confidence in the referral pathway. This suggests that healthcare system factors, such as nurses’ training in supporting emotional distress, current structures of diabetes and mental health care, and organisational leadership around introduction of screening programmes, are important areas to consider for the successful introduction of diabetes distress screening.

Implications for clinical practice and service improvement

- Introduction of a diabetes distress screening programme is a complex intervention requiring exploration of the past and current practices related to sup-porting mental health of people with diabetes and nurses’ experiences of such practices.

- Diabetes distress screening implementation programmes should be co-developed with the frontline staff who will carry out screening to make it acceptable and feasible alongside existing clinical priorities.

- Successful adoption of screening may depend on nurses’ confidence in: i) their own ability to support emotional needs, and ii) in the available support and referral network.

- Introducing diabetes distress screening without giving DSNs appropriate training, time and referral pathways may result in emotional distress to them. In-depth training in working with diabetes distress within clinical consultations is needed, informed by a framework for guiding non-mental health-trained clinicians in ways to manage emotional well-being in clinic, such as the 7As model (Be Aware, Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist, Assign and Arrange; Hendrieckx et al, 2019).

- Development and testing of diabetes distress screening in clinical practice may benefit from a quality improvement approach that enables the intervention to be shaped by those involved.

- Access to psychological services is limited, which has an impact on screening for distress and escalation when/if found.

Limitations

A small number of participants were interviewed for this study and, thus, there may have been a wider range of experiences than reported here. As only DSNs were interviewed, perspectives of other clinicians and people with diabetes on the intervention are missing. However, by focusing on nurses’ voices as those carrying out the screening, this study has elucidated a previously under-reported central tension between nurses’ recognition of the benefits of screening for emotional distress among people with diabetes and fear of being unable to meet this need due to a range of individual and systemic factors.

Conclusion

DSNs perceive the idea of routine screening for diabetes distress in their clinics as potentially beneficial, with more people with diabetes having their diabetes-specific emotional needs recognised and addressed. However, they have concerns about the practice of screening becoming “a tick-box exercise” or, on the other hand, leading to the opening of a “Pandora’s box”. While addressing the emotional needs of people with diabetes is key to diabetes care, many aspects of the practice of screening (e.g. which healthcare professionals, when, how, with what tools, with which patients and how to follow up/how to support within and beyond the clinic) remain in need of further exploration.

Acknowledgements

Jane Maskell and Jane Salmon; the Oxford BRC Diabetes Reference Panel.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Appendix. Flow sheet for actions after receiving Diabetes Distress Scale score.

Developments that will impact your practice.

22 Dec 2025