| The new NG246 replaces several guidelines, including: • CG43: Obesity prevention (2006) • CG189: Obesity: identification, assessment and management (2014) • NG7: Preventing excess weight gain (2015) • PH42: Obesity: working with local communities (2012) • PH46: BMI: preventing ill health and premature death in Black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups (2013) • PH47: Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese children and young people (2013) • PH53: Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese adults (2014) |

Language and approach

● There is a significant shift in emphasis regarding principles of care in terms of the approach and language used with regard to overweight and obesity. This reflects increasing awareness that overweight/obesity can be multifaceted and increasing awareness of harm from stigma.

● Before discussing overweight/obesity, care should be taken to ensure:

- Is this the right time/context for the discussion?

- What wider social determinants of health are present for this person?

● General health, comorbidities, medications, recent pregnancy, experiences of stigma, childhood trauma, ethnicity and financial worries should all be considered.

● Ask permission to discuss weight and respect the person’s choice, including delaying or declining to discuss.

| Use non-stigmatising (person-first) language such as “living with obesity” Identify the person’s preferred terms |

● Stay positive, supportive and solution-based. Use this visual summary to improve communication about overweight/obesity.

● The guideline extensively details considerations for clinicians prior to discussing weight, given increasing understanding of the impact of the stigma associated with overweight and obesity – particularly in the context of patient–clinician relationships.2 If handled insensitively, people living with overweight and obesity may be reluctant to engage in discussions around weight in the future, and consequently suffer significant physical and psychosocial sequelae.

● Clinicians should consider their own feelings and sensitivities about weight prior to engaging. Avoid “diagnostic overshadowing” – where a patient presents with another condition (e.g. knee pain) but the clinician first moves to discuss weight; the presenting condition should be addressed first.

Diagnosis

● Both BMI and a measure of central adiposity such as waist-to-height ratio should be calculated as a practical estimate for evaluating health risk.

● Educate patients to monitor their own weight and waist measurements correctly (do not measure waist if BMI is over 35 kg/m2, as above this level measurements are not accurate).

| Measure: • Height • Weight • Waist circumference in people with BMI below 35 kg/m2 BMI and waist-to-height ratio should be calculated. |

| Ethnicity Those from some ethnic minority backgrounds are more prone to central adiposity and are therefore at increased risk of weight-related conditions at a lower BMI. It is important to ensure that both clinicians and patients are aware of this increased risk and the appropriate BMI cut-offs used. |

Discussion of results

● Ensure you are aware of local and national services for support. Give information regarding the degree of overweight/obesity and associated health risks. Offer advice and discuss the possibility of referral.

● Try to identify and address the drivers of overweight and obesity for the individual. Consider referral for comorbidities or services such as social care, physiotherapy, eating disorders and wellbeing services.

● Discuss and agree personalised goals; for example, finding it easier to breathe when going up the stairs at home, or being able to play with grandchildren.

● Whatever the strategy, long-term support will be needed.

Dietary approaches

● These must be flexible; no one size fits all. The aim is to achieve nutritional balance whilst reducing energy intake.

● Consider following a diet related to reducing a specific macronutrient (e.g. low-fat or low-carbohydrate diets). Intermittent fasting is not specifically recommended. The aim is to ensure that dietary approaches for adults keep the person’s total energy intake below their energy expenditure.

● Consider:

- Food preferences.

- Cultural preferences.

- Personal circumstances, such as ability to prepare food and availability of equipment to do so.

- Neurodiversity.

- Comorbidities.

● Low- and very-low-energy diets are only recommended under supervision via specialist weight management services, with very-low-energy diets recommended only in specific circumstances (such as weight loss needed for surgery), and for limited time periods (maximum 12 weeks). Excessive restriction can lead to weight cycling and regain, and should not be encouraged outwith the above circumstances.

● Discuss the importance of improving diet even if weight loss is not achieved (other benefits could include improved lipid profile, reduced risk of diabetes, etc.).

● Over the long term, a nutritionally balanced diet is key (see NHS Eat well). Weight regain should not be seen as failure.

● Support with a dietitian or UKVRN-registered nutritionist is recommended for all dietary changes which maintain an energy deficit, although in practice this may be difficult to achieve.

● Consider that eating disorders can coexist at any weight and may make particular diets inappropriate.

Physical activity

● There are no specific changes to advice. Physical activity should be encouraged even if weight is not lost as a result.

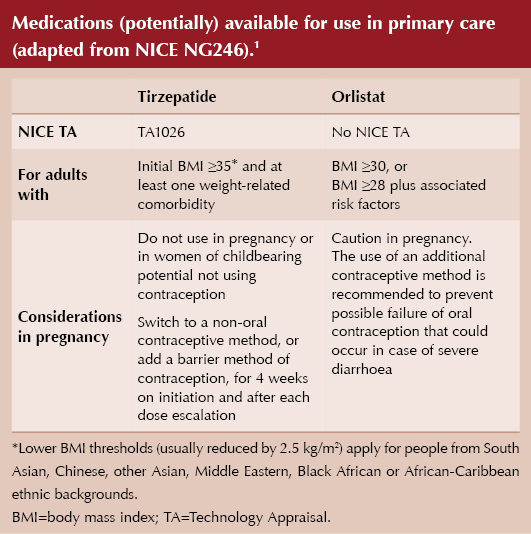

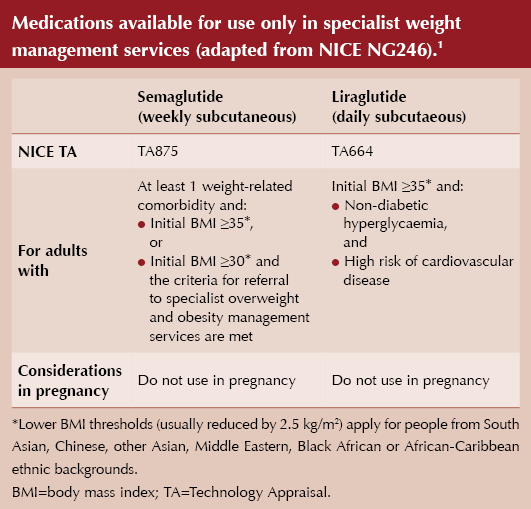

Medication

● Medication should be considered after behavioural approaches have been instigated and evaluated.

● Incretin mimetics have completely changed the landscape of obesity care. Tirzepatide is currently approved for use in primary care from 23 June 2025,3 but details may vary between ICBs. Interim commissioning guidance from NHS England was published on 27 March 2025.4

● A stronger emphasis has been placed on encouraging adherence to management interventions. The need for ongoing support is emphasised given the chronic nature of overweight and obesity. Services are not necessarily resourced to do this.

● Particular attention to ensuring any intervention considers individual factors may improve adherence.

Footnote: Although not specified in the NICE guidance, clinicians should be aware of the importance of muscle loss associated with the use of incretin-mimetic drugs for weight loss. Strategies to mitigate this are discussed in Diabetes Distilled.

Service delivery

● Both NG2463 and TA10265 indicate a move away from tiered systems and instead discuss a wide range of services for overweight and obesity management, described in NG246 as:

- “Universal services such as health promotion or primary care (sometimes referred to as tier 1 services).”

- “Behavioural overweight and obesity management services (sometimes referred to as tier 2 services).”

- “Specialist overweight and obesity management services (sometimes referred to as tier 3 and tier 4 services).”

Specialist services

● Referral for specialist interventions, including further medication options (semaglutide and liraglutide) and surgery, should be considered if the person has complex disease (e.g. BMI >50 kg/m2 or BMI >35 kg/m2 alongside certain comorbidities), or if less intense management has been unsuccessful.

● There is no change to previous guidance regarding surgery.

Children

● Children are included in NG246, again with emphasis on communication and individual choice.

● BMI can be used as a practical estimate for overweight and obesity, but charts used for interpretation must be specifically designed for this purpose. Stage of puberty must be considered. Charts such as UK–WHO growth charts, 2–18 years must be consulted.

● Similarly to adults, weight should only be discussed with permission from the child or caregiver.

● The degree of overweight/obesity and the potential health consequences should be discussed. Drivers for overweight and obesity must be considered.

● Individual targets should be set – for children who are growing taller, avoidance of weight gain whilst continuing to grow is appropriate. Targets could include improvements to wellbeing and self-esteem rather than only weight. Families/carers and young people should be encouraged to take responsibility for behavioural change.

● If weight or weight-related comorbidities pose a threat to health and wellbeing, refer to relevant support services.

● The importance of long-term support is emphasised, with the advice that only services offering long-term support and maintenance advice should be referred to.

Prevention

● Prevention features heavily in the guidelines, with particular emphasis on prioritising appropriate nutrition and activity for children in early-years settings.

ICBs in England are undergoing a major restructure. Guest editor Hannah Beba asks how this might affect diabetes care.

9 Jul 2025