Ensuring that clinical psychologists work as part of paediatric diabetes care in the UK has been seen as fundamental since the introduction of the Best Practice Tariff (NHS Diabetes, 2012). As clinical psychologists we were therefore delighted to be invited to take part in a project to improve the lives of children and young people (CYP) with type 1 diabetes (T1D) in Botswana and the UK. In this article, we describe the project, the impact diabetes has on CYP in Botswana, our input, the feedback received, what we learned, how this will impact our practice in the UK and our hopes for future collaboration with healthcare professionals from Botswana.

The Botswana Paediatric Diabetes Partnership Project

Cambridge Global Health Partnerships (CGHP) is Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust’s global health programme. It aims to support and enable NHS staff from Cambridge University Hospitals to train and support health workers in low and middle income countries through global health partnerships. In collaboration with the East of England Children and Young People’s Diabetes Network, CGHP created a partnership project that aimed to improve diabetes outcomes for young people from both Botswana and the UK.

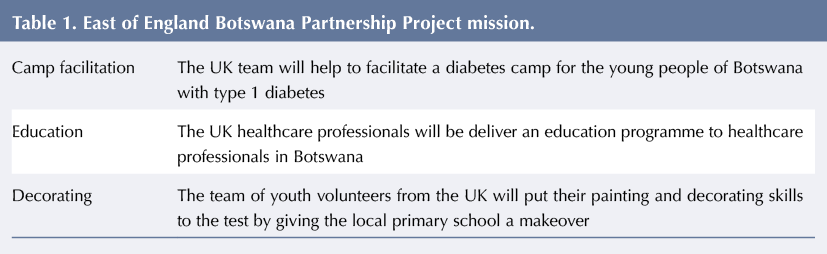

We joined a skilled team of professionals (including doctors, nurses, a dietician and a parent representative) and 12 young people from the East of England who have T1D. The project had a mission consisting of three elements, see Table 1. It provided the opportunity for a mutual exchange of knowledge and experiences for both young people and professionals (Nelson et al, 2019). Broadly divided into two parts, the project involved:

- Joining a 2-day diabetes camp for CYP co-facilitated by the Botswana Diabetes Association and the East of England Children and Young People’s Diabetes Network

- Delivering a 3-day educational symposium to healthcare professionals working with CYP with diabetes from across Botswana.

Residential Camp, Mokolodi

The residential camp at Mokolodi takes place once or twice per year and is open to all young people with diabetes in Botswana. Its facilitation is dependent on charity funding and on healthcare professionals and youth leaders volunteering their time and skills. Participation in the diabetes camp enabled us to hear about the experiences of Botswanan CYP living with T1D, as well as meeting with youth leaders to hear about their personal and professional experiences of T1D.

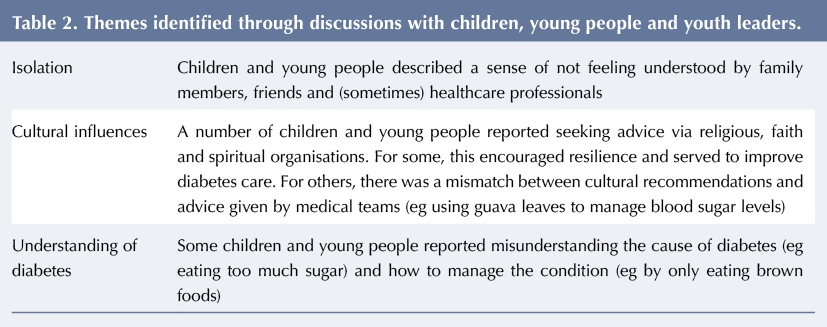

Youth leaders are young adults living with diabetes who volunteer as part of the Botswana Diabetes Association to support CYP. As part of the camp, the youth leaders offer a space where young people are encouraged to talk about the emotional impact of being diagnosed with T1D around a camp fire. This provided us with the opportunity to hear about the struggles and strengths of Botswanan CYP living with diabetes and their families. A number of themes were identified from this discussion, see Table 2.

Hearing the mixed experiences of young people and youth leaders was very influential in shaping our ideas about the teaching to be provided to healthcare professionals at the later symposium. In collaboration with the Botswanan youth leaders, we added specific slides entitled ‘♯iwishtheyknew’, which captured messages from CYP about what they would like their families, friends, healthcare professionals and society to know about their experiences.

Educational symposium, Gaborone

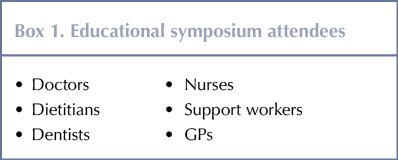

Prior to preparing for the educational symposium we had an open mind about what information we were going to deliver to healthcare professionals, see Box 1.

We were mindful throughout of our position in coming to offer training in Botswana, including maintaining cultural sensitivity in our delivery. With this in mind we:

- Provided an overview of psychological approaches used by psychologists working within paediatric diabetes teams in the UK.

- Introduced psychological techniques and models that could be used by healthcare professionals, with the aim of building on their existing skill set to draw the best from their consultations with CYP. This included introducing the biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977), motivational interviewing techniques (Miller and Rollnick, 2012) and solution-focused techniques (eg Viner et al, 2003; Guyers et al, 2019).

- Incorporated feedback from Botswanan CYP on what they would like healthcare professionals to know about their experiences, and how this could inform discussions with CYP attending their clinics.

Feedback from the symposium

A total of 130 healthcare professionals attended the 3-day conference, which was also attended by the British High Commissioner for Botswana as well as representatives from the university and the Ministry for Health in Botswana. As there were no clinical psychology contacts in the Botswana paediatric diabetes teams, we were initially unsure of what prior knowledge healthcare professionals would have about psychological approaches utilised in diabetes management. We were struck by how well the psychology teaching was received; of the 82 feedback forms received, attendees on average gave the psychology teaching a rating of 9 out of 10 for helpfulness.

Themes arising regarding the psychology teaching included:

- The impact the teaching would have on how delegates work with CYP within their consultations:

‘I believe the diabetes and psychology lecture will strongly influence the way we practice management of diabetes in children and adolescents.’

‘Psychological aspects are very important when dealing with diabetes clients because it can help find the root cause of uncontrolled DM.’ - The novelty of a psychological approach:

‘Loved this [teaching]. An eye-opener!’

‘[It was most helpful] learning about psychological aspects affecting patients with diabetes because usually I tend to focus more on the biological aspect.’ - The desire to have psychology work as part of their healthcare teams:

‘[Psychology] needs to be rolled out in Botswana… as there is a shortage of psychologists in Botswana.’

‘We need more clinical psychologists who are equipped with diabetes management [skills].’ - The usefulness of hearing about the experiences of CYP living with diabetes:

‘The sharing of personal information by young children living with diabetes [was most useful].’

‘It was helpful to hear from the young people that came to share their experiences with us.’

Reflections

We were struck by the privileged position we have in the UK, where policies and systems are in place to ensure that the psychological wellbeing of CYP and their families are considered an integral part of holistic care. The overwhelming feedback from the symposium was bittersweet; it highlighted the importance of the role of psychological wellbeing for CYP, but also the restraints within the country’s system whereby changes in diabetes services to incorporate psychology are likely to take time.

One of the themes that stood out for us was cultural references in relation to knowledge about T1D and being respectful of this, see Table 2. Having briefly met CYP on the camp, we were struck by their openness when talking about how difficult living with diabetes has been for them. We found CYP to be vocal about the hard and dark times they experienced with diabetes and how this, for some, led to severe depression, self-harm and attempted suicide. There was a sense of feeling isolated and not understood by those who did not have T1D.

What we would have done differently

We would have been keen to support those healthcare professionals who are continuing to implement change through psychological thinking and techniques – ie the use of the biopsychosocial model or motivational interviewing techniques – in the longer term. Although this was not something that could be facilitated on a regular basis, we were pleased to hear that some healthcare professionals from Botswana plan to travel to the UK in 2020 in order to learn more about the support that is offered here. During that time, we hope to enable them to gain further insight into the role of clinical psychologists working within paediatric diabetes in the UK.

We were grateful to delegates who were very reflective of their practice and spoke about times when they felt stuck and deskilled in knowing how to best support their patients. We were aware of the strain on psychology resources in the country, with estimates of only one psychologist employed to support CYP with diabetes in Botswana. Ideally an exchange of experiences and knowledge with the psychologist would have been a rich learning experience for all parties. Indeed, we would have liked to co-facilitate our teaching at the educational symposium with mental health professionals from Botswana, although this was not possible due to limitations in resources.

What we have learnt

We believe that the model of youth leaders with T1D supporting CYP is an approach that could be better utilised in the UK. Of those services that have drawn on the expert-by-experience model of peer support, groups with peer facilitators have been shown to have positive experiential outcomes whereby there is a shared sense of feeling understood by someone having the same health condition (eg Casdagli et al, 2019). The power of shared experiences and personal discourses was a theme that carried through the residential camp.

There was a prevailing message throughout the project that was initiated by one of the Botswanan consultant paediatric endocrinologists. In summing up the current project, he quoted the African proverb: ‘If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together’. As psychologists passionate about the emotional wellbeing of CYP with diabetes, we hope that this represents the beginning of a relationship that will enable CYP from both the UK and Botswana to have better physical as well as mental health outcomes.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022