From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the remit of podiatry services across the country has been “hospital admission avoidance” and “saving limbs”. Diabetes foot problems are the most common causes of diabetes-related hospital admissions in the UK (Boulton and Whitehouse, 2020), are usually preceded by serious foot infections and can result in amputation. The importance of timely action, especially in the infected and ischaemic diabetic foot, is highlighted in the term “time is tissue” (Vas et al, 2018).

At the beginning of the lockdown, it seemed probable that there would be a fall in referrals and so it has been paramount for NHS podiatry services to communicate to all stakeholders that podiatry services and multidisciplinary diabetic foot teams (MDFTs) have continued to run for those people with active foot disease. It has been important to come together across the disciplines to support each other, and to work closely with good communication and timely referrals.

Delivery of care

Prior to the lockdown, people with complex diabetic foot problems were generally seen weekly in podiatry clinics, community clinics or acute MDFT settings. In light of the outbreak and the diversion of resources, there have been different delivery strategies for diabetes foot disease management. Providing care during these times has remained crucial, under the remit of “hospital admission avoidance”. Individuals who normally attend diabetes foot clinics have still required regular and close surveillance to achieve optimal outcomes and limb salvage.

Services have implemented local and national guidance to adapt delivery of care to support these vulnerable individuals during this difficult time:

- Telephone hotlines for diabetes foot problems (if previously not in place).

- Telephone triage service.

- Increased domiciliary caseloads, for people self-isolating/shielding.

- Virtual MDFT clinics and satellite foot clinics.

Podiatry services and MDFTs have adapted approaches to care delivery, with remote consultations being used where possible. MDFTs have linked up “virtually” with patients in satellite/community clinics or in their own homes. Delivery of MDFT clinics through video conferencing has enabled people to have an MDFT consultation without needing to attend an acute hospital site. This has served to strengthen communication and pathways between community services and hospital MDFTs.

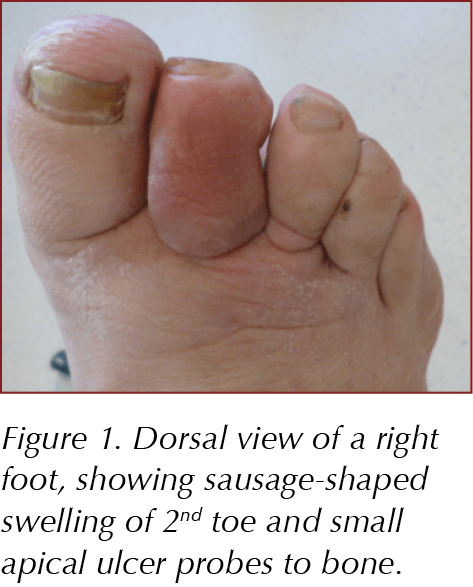

The outpatient management of diabetes-related complications and the ability to order basic tests have been severely restricted in some areas. Additionally, many people who are shielding have declined to attend for diagnostic tests, such as radiology and vascular scans. Good clinical examination and history-taking has been essential: for example, osteomyelitis in a toe can be suspected by clinical “sausage-shaped toe swelling” (Figure 1) and a positive probe-to-bone test (if radiology is not an option; Rajbhandari et al, 2000). Vascular examinations have been carried out using good clinical examination and handheld Dopplers. Patients presenting with more urgent vascular concerns should have been directed to acute vascular services for further diagnostic testing and surgical intervention.

Podiatrists have had to continue to be vigilant with patients and work quickly to help prevent serious complications. Surveillance of these people during this challenging time is more difficult and requires face-to-face consultations. The issue is that people with peripheral neuropathy may be less likely to seek medical help when needed owing to the loss of pain sensation and lack of awareness of their foot problem (Figure 2).

Communication and interdisciplinary team work

Podiatrists have continued to work closely with general practices and community nursing and tissue viability teams to enable optimisation of assessments, reviews and treatment plans for the complex patients, including those in care homes. The crisis has encouraged greater interdisciplinary teamwork and appreciation of what other services can offer. Timely and appropriate referrals will only improve outcomes due to better care. Improved diabetes foot care reduces the risk of amputations, saves lives and saves money (Diabetes UK, 2013).

In the “new normal”, we have the opportunity to change the way we work to improve both current and future clinical services. We are developing an increased appreciation of what each profession/team can offer for better collaboration and patient outcomes. The use of technology for access to remote MDFT consultations can maintain high-quality care and improve patient journeys, with stronger links between community and acute services.

Patient education

For people with diabetes, education and diabetes foot checks are integral to improving care. Healthcare professionals must encourage people with diabetes (or a carer/family member) to check their feet daily. Diabetes UK provides simple steps to prevent foot problems and tips for everyday foot care: bit.ly/3j8SPDD.

There needs to be emphasis on the importance of urgently reporting to the practice any blisters, wounds, signs of infection, changes in colour and shape of feet, or other concerning features. Education videos, such as the one provided by Diabetes UK, can show people how to check their feet thoroughly and highlight the signs of a serious foot problem: bit.ly/3h8yj3V.

A quick and easy test for sensation can also be performed at home with a carer or family member. A short video shows how: bit.ly/2Bcb6Pc.

Annual foot assessments (undertaken by a trained healthcare professional) must be continued, where possible. Several certified e-learning diabetes foot screening courses are available to help standardise diabetes foot screening performed by healthcare professionals (e.g. www.diabetesframe.org).

Conclusion

Appropriate care, education and timely referral are essential for people with diabetes foot disease during lockdown and will continue to be afterwards.

The danger is that those who have “lost the gift of pain” because of diabetic peripheral neuropathy (Boulton, 2013) will be less likely to seek medical attention when needed. For those who delay seeking medical attention, the result may be the need for surgery and amputation due to delayed intervention. Timely referral is essential, along with strong inter-professional communication.

Diabetes foot care awareness needs to continue to be raised, and access to appropriate and timely care improved. Patients must be encouraged to check their feet daily and to seek medical help during these times. An important message is, lockdown or no lockdown, we are all still here to care for people with active diabetes foot disease.

Resources

Prevention and management of diabetic foot disease. Guidance documents to inform healthcare professionals on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease.

International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) 2019 guidelines: bit.ly/3eATVnR

Treating people with diabetes with footcare problems. A commentary written for all healthcare professionals.

Diabetes Foot Care in the COVID-19 Pandemic: bit.ly/3fEyFPA

Preventing foot problems. Simple steps and tips for everyday foot care.

How To Look After Your Feet: bit.ly/3j8SPDD

BPROAD study: Reducing systolic blood pressure to <120 mmHg versus <140 mmHg in people with type 2 diabetes reduces cardiovascular events.

3 Apr 2025