Based on current estimates, there are nearly 400,000 people living with type 1 diabetes (T1D) in the UK, of which 8% are aged 19–25 years (Scottish Diabetes Data Group, 2017; NHS Digital, 2018). The period of young adulthood represents a significant time in the health and wellbeing of the population, with most assuming financial independence from parents, moving home, forming new relationships, entering the workforce and adopting new social habits (Arnett, 2001). In the process, young adults face unique challenges (developmental, lifestyle, healthcare and psychosocial) in trying to balance these important changes with the management of T1D (Monaghan et al, 2015). As a result, outcomes in this age group are among the most suboptimal: <30% achieve treatment targets for glycaemic control or receive all nine National Institute for Health and Care Excellence-recommended care processes (NHS Digital, 2018). Peak mean HbA1c is encountered (Foster et al, 2019) and one-third of young adults live with some level of diabetes-related distress (Hagger et al, 2016). Relatively higher rates of emergency admissions are seen in young adults with T1D with or without other chronic health conditions (Fortuna et al, 2010). While engagement rates with medical professionals are lowest in this age group (Callahan and Cooper, 2010), there is also evidence to suggest that healthcare-related bureaucratic problems contribute to ‘missed appointments’ (Snow and Fullop, 2012). An informal calculation has shown that people with diabetes spend 99.9% of their time managing their condition independently or relying on peers, without any professional support, highlighting the importance of peer support in T1D (Hernandez, 2015).

The Liverpool challenge

Liverpool is home to four universities, two Premier Football Academies and a historic music culture, playing host to a population of approximately 500,000 people, 42% of whom are aged <30 years (Office for National Statistics, 2018). The care of young adults with diabetes is spread across the city through primary care and three teaching hospitals (two adult and one paediatric). This article elaborates on the service and outcomes in one of the adult hospitals: the Royal Liverpool University Hospital. In 2015, specific challenges in the provision of young adult diabetes care at this hospital included:

- High non-attendance/did-not-attend (DNA) rate

- Low numbers achieving target HbA1c

- A high percentage of the clinic cohort being admitted with diabetes-related emergencies

- An absence of local peer-support platforms.

If these trends continued, there was the potential for reduced self-management, screening for complications and wellbeing in this vulnerable population. Previous attempts to introduce innovative care had been hampered by a lack of resources and funding.

Model for change

To address problems, it was decided to implement a structured, cohesive, person-centred young adult diabetes service. The results of local National Institute for Health and Care Excellence-related and national audits, service evaluation studies and performance reviews were used to identify challenges and pitfalls in the service. Young adults were invited to focus group meetings to feed back, generate ideas and aid in service design. A new model of care was set up with the over-arching aim of engaging, supporting and empowering young adults. It incorporated specific objectives:

- To reduce the DNA rate

- To increase the percentage of young adults achieving HbA1c <58 mmol/mol (7.5%), in line with National Diabetes Audit targets

- To reduce the median HbA1c of the clinic

- To reduce young adult hospital admissions due to diabetes-related emergencies

- To improve access to the clinic and healthcare professionals (HCPs)

- To establish a local peer-support platform to empower young adults with diabetes and improve their self-management skills.

Year 1 changes

The changes implemented in Year 1 (2016) were sub-classified into four broad themes and were related to clinic structure, communication, support and outcomes measurement.

Clinic structure changes

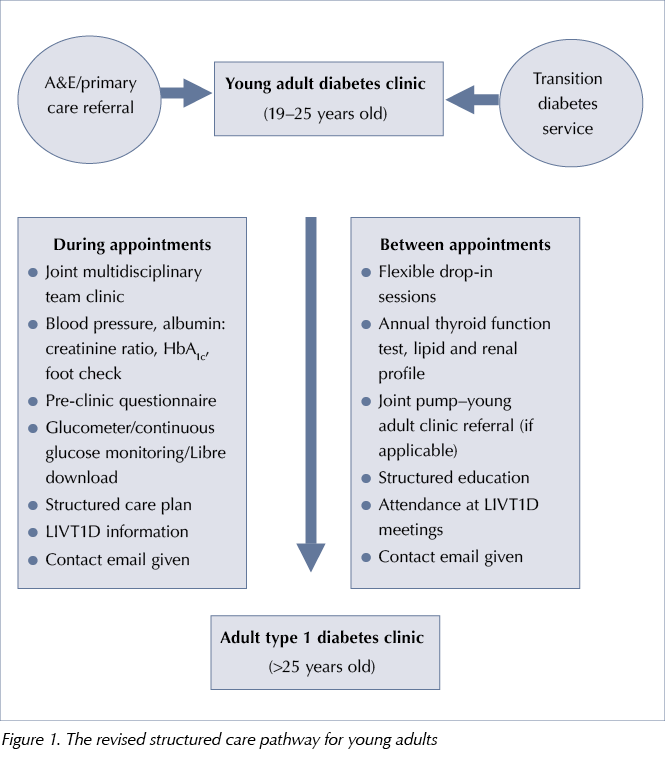

The structured care pathway was revised, with a defined population age group, sources of referral, services offered during and between appointments, and transfer to the adult clinic under the same consultant to ensure continuity of care, see Figure 1. Joint weekly multidisciplinary team (MDT) clinics with 4-monthly follow-up appointments were introduced, with the consultant, diabetes specialist nurse and dietitian in attendance. This was in line with the clinic structure in the local paediatric and transition diabetes clinics, avoiding the need for multiple individual appointments with different HCPs. Flexible ‘drop-in’ appointments were embedded into the nurse- and dietitian-led clinic templates on specific days of the week to ensure review of those patients who missed their formal young adult clinic appointments.

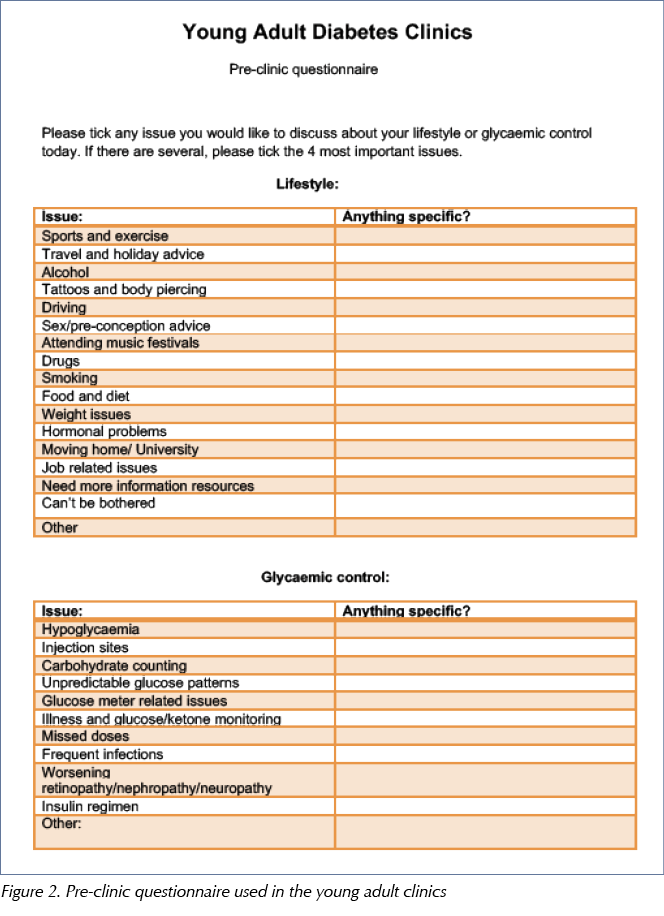

A pre-clinic questionnaire, see Figure 2, was handed to young adults while in the waiting area of the diabetes centre. This was an idea adopted from transition diabetes clinics in Portsmouth (Kar et al, 2014). Patients are asked to highlight their most important diabetes- and lifestyle-related areas of discussion during the consultation.

Glucometer, insulin pump and flash/continuous glucose monitor data download was implemented through a variety of pieces of software. While it is relatively standard practice in 2019, in-house data download was still novel a few years ago.

Communication changes

Telephone reminders for appointments were introduced. Calls were made by a departmental secretary in addition to the standard text message and appointment letters sent by the hospital. Patients were given the email address of an individual HCP within the MDT that they could contact for advice during working hours. In addition to this, young adults were advised to contact the team within 2 weeks of a clinic appointment to jointly analyse trends in glucose levels following any changes made in the previous clinic and to maintain contact between appointments.

Support changes

LIVT1D, Merseyside’s first peer-support group for adults with T1D, was established with the help of people with diabetes and HCPs. Support is extended via:

- Closed online social media platforms (managed by young adults)

- Social gatherings

- Three-monthly educational meetings held from 6–8 pm at a local hotel, funded through health technology organisations and department charity funds.

Outcomes measurement

A comprehensive database of the clinic cohort was created. This database has incorporated demographic and clinical data for measuring clinical outcomes, in addition to conducting audit and research.

Years 2 and 3

Further changes were made in 2017 and 2018. First, a joint young adult–insulin pump MDT clinic was set up to align care given to young adults on insulin pumps with the well-established protocols of the adult cohort under the Royal Liverpool Insulin Pump Service. This serves as an ideal platform for discussing challenging cases and clinical conundrums. Second, primary care colleagues caring for university students were invited to attend young adult diabetes clinics. This reassured them of the care students with T1D received from the specialist service and strengthened relationships across the healthcare spectrum. Third, FreeStyle Libre education sessions were introduced following the national implementation of flash glucose monitoring prescription (Regional Medicines Optimisation Committee, 2017). While this was applicable to the entire T1D service, significant numbers in the cohort were young adults.

Results

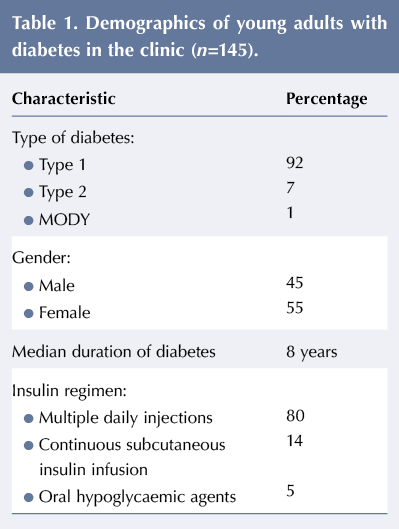

The demographics of the clinic cohort are given in Table 1. Data from the clinic database, hospital laboratory system (Sunquest ICE®) and bespoke online diabetes register were used to analyse outcomes. Results from 2015 (baseline year) were compared to those at the end of 2018 and categorised into: clinic attendance; median HbA1c; percentage achieving HbA1c ≤58 mmol/mol; and hospital admissions with diabetic ketoacidosis and severe hypoglycaemia.

Chi-squared and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to analyse the data. IBM SPSS Statistics 2015 software was used to perform statistical analysis.

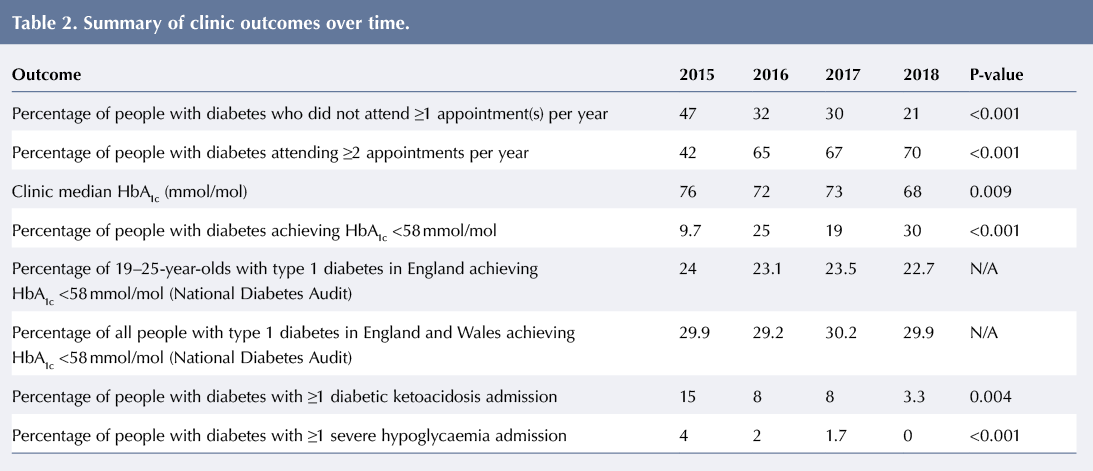

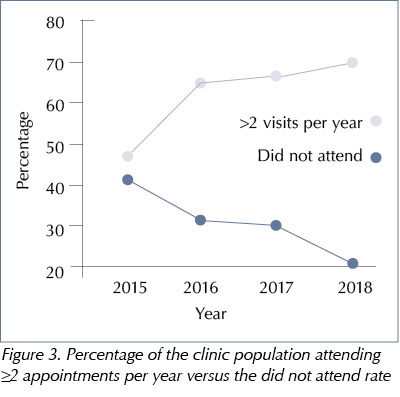

A significant reduction in the DNA rate was seen between 2015 and 2018 and the percentage of people with diabetes attending two or more clinic appointments per year peaked in 2018, see Table 2 and Figure 3.

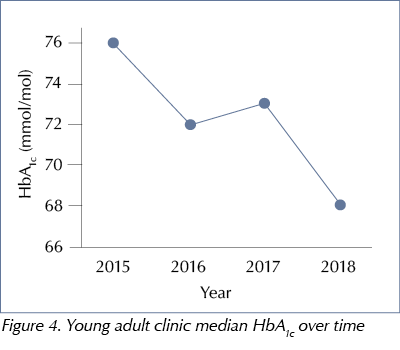

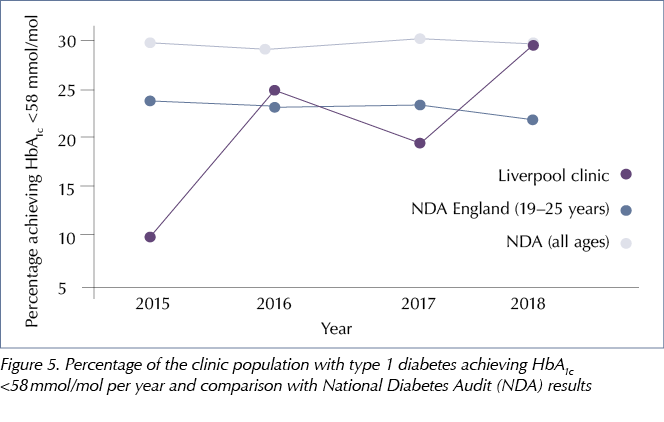

There was a steady fall in median HbA1c – from 76 mmol/mol (9.1%) to 68 mmol/mol (8.4%) –between 2015 and 2018 (P=0.009), see Figure 4. By 2018, nearly a third of young adults had achieved a median HbA1c <58 mmol/mol compared to just 9.7% in 2015 (P<0.001), see Figure 5. This was above the national median for people with T1D in the same age group (22.7%) and similar to the observed median in the UK for people with T1D across all ages (29.9%) (NHS Digital, 2019).

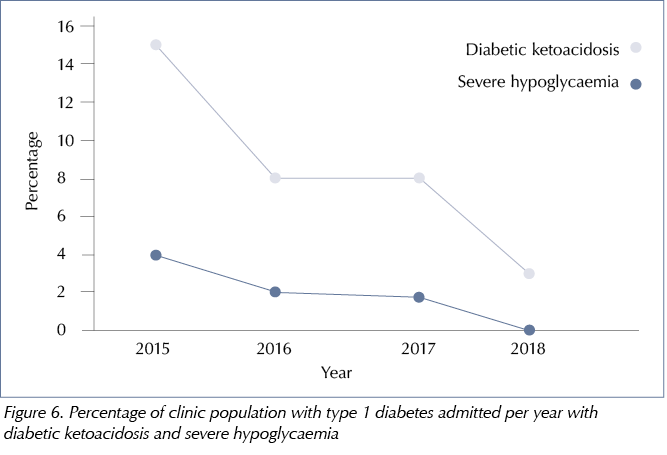

Hospital admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis dropped from 15% in 2015 to 3.3% in 2018 (P=0.004), see Figure 6. None of the young adults attending the service were admitted with severe hypoglycaemia in 2018 (P<0.001), see Figure 6.

Feedback from young adults about the clinic and LIVT1D meetings has been encouraging, with satisfaction rates of 85% and 100%, respectively. LIVT1D has expanded steadily over the past 3 years, with over 250 members now supporting each other across Merseyside. Its rising popularity has generated interest from influential organisations and resulted in one of the local Premier League football clubs formally being associated with the group, hosting meetings and further spreading awareness of T1D.

Limitation

The limitation of these data is that they cover the young adult diabetes service in one teaching hospital and not the entire city.

Lessons learned

A key feature of this service model has been the co-design with young adults. Research suggests that this can lead to improved outcomes (Locock et al, 2014). Seen not as ‘patients’ but ‘experts through their experience’, the young adults have been able to identify crucial problems and provide valuable solutions to their HCPs, who have merely been ‘facilitators’ in this process. This in turn has empowered young adults, strengthened relationships with HCPs and increased engagement both ways.

Inertia in initiating and implementing change can be overcome by services identifying issues that are under their ‘direct control’ and worrying less about those that are not. This theory, described by Covey (1989), proved highly effective in identifying pitfalls in our service and designing the new pathway. The changes described have been implemented by adopting the core philosophy of being person-centred and addressing the basics without getting entangled in complex NHS bureaucracy.

‘Innovation’ and ‘expensive’ are not always synonymous. It is crucial to take into consideration that, apart from securing funding for LIVT1D meetings, no additional funds were used or staff hired in this process of change over 3 years. The changes adopted by our model have thus involved minimal financial investment but maximum amendment in attitude, work ethic and approachability.

Conclusion

Achieving optimum care for young adults with diabetes has often been the ‘holy grail’ for adult healthcare services. Young adults face unique challenges that are vastly different from the older population that adult HCPs are more accustomed to seeing.

The late author Wayne Dyer once said, ‘Change the way you look at things and the things you look at change’. Young adult diabetes care needs services that are striving to engage more with people with diabetes through simplistic or innovative methods. The outcomes achieved in Liverpool are a testament to the involvement of young adults at every level – be it co-designing the pathway, delivering highly-appreciated peer support or providing regular feedback. Additionally, HCPs have adopted a flexible, engaging and relevant approach to the needs of young adults. The outcomes are relatively short-term to date, but are continuously improving. Challenges remain, with lack of psychology provision and variations in access to diabetes-related technology across clinical commissioning groups being the most obvious. These challenges, along with the overwhelming burden of managing the complications of type 2 diabetes, are not unique to Liverpool but seen across adult services nationally. Critically, the discrepancy in funding between paediatric and adult diabetes care contributes to the disparity in care given to young adults across services. While our service has implemented simple and effective changes, further innovation will undoubtedly require financial investment. Paediatric diabetes care has benefitted hugely from the adoption of the Best Practice Tariff, resulting in markedly improved outcomes nationally (Randell, 2019; RCPCH, 2019). Although some variation in care still exists despite this funding, important lessons are to be learnt in the era of the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS Improvement, 2019). Discussions may be needed about adopting a bespoke financial package aimed at the care of 19–25-year-olds with diabetes to improve access to services, strengthen support and prevent long-term complications in a vulnerable age group.

Acknowledgement

The authors are immensely grateful to the members of LIVT1D for their immeasurable support, ideas and contribution in improving the Young Adult Diabetes Service at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022