The latest evidence to be reported at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes meeting, held in Barcelona in September, reinforces the benefits to be seen over and above that of glucose lowering. We have discussed the beneficial effects on renal protection recently (Morris, 2019), and further trials have reinforced this amazing outcome and obvious benefit from using the class early in type 2 diabetes.

Of equal interest is the prevention of hospitalisation from heart failure (HF) and the prevention of HF itself, with many more trials currently ongoing in this area. This news is incredible as heart failure has such a massive impact on quality of life and the outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes are so very poor. It is estimated that, for those with both type 2 diabetes and HF, the risk of cardiovascular mortality and death from worsening HF is 50–90% greater than for those with HF alone (Kristensen et al, 2017).

The recognition of HF in our patients with type 2 diabetes could be and needs to be better. The prevalence of diagnosed HF in those with type 2 diabetes is a staggering 20–30%, and the risk of developing HF once diabetes is diagnosed is 2–5 times higher (Nichols et al, 2004). More worryingly, the risk of developing HF is also significantly raised in those with prediabetes (Matsushita et al, 2010), posing us a huge future problem. This increased risk of HF in the prediabetes population suggests an alternative causality from the previously assumed long-term poor glycaemic control causing atherosclerotic changes.

Not only is there a risk of developing HF in those with diabetes but, conversely, the risk of developing diabetes is far higher in those with HF (Amato et al, 1997). The more severe the HF the greater the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and the outcomes, sadly, are poorer. These factors reinforce the importance of screening for diabetes in the HF population.

Hospitalisation from HF is a factor we simply have to improve our awareness of, as people with type 2 diabetes tend to stay in hospital for a longer duration, with far worse outcomes than for those without diabetes (Targher et al, 2017). As diabetes specialists, we need to work more collaboratively with our HF nurse specialist colleagues to ensure we are all contributing to the multidisciplinary discussion and care plan going forward.

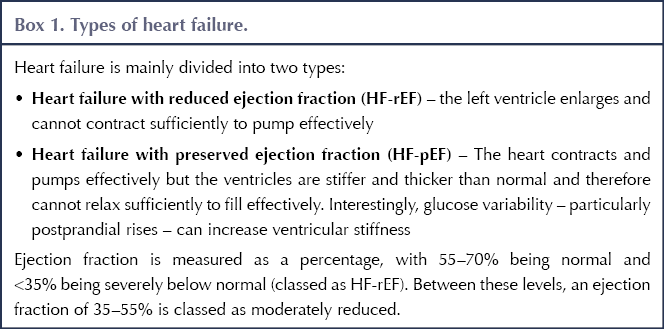

People with diabetes can have HF with preserved, moderately reduced or reduced ejection fraction (Box 1), and the positive outcomes of the SGLT2 inhibitor class can be seen across the whole spectrum of this condition (Kateo et al, 2019).

As our knowledge of the benefits of this class in HF grows, it is vital that we in turn increase our awareness of HF in our patients. Questioning for signs and symptoms of HF (Box 2) should be part of our normal routine discussions and, once diagnosed, discussions regarding progression should be key.

When having these discussions in our clinical practice, it is easy to regard symptoms of fatigue and shortness of breath as a result of poor glycaemic control and being overweight. I believe we now have to consider that these symptoms could be early signs of HF, and part of our assessments and planning should be to aim to get a clear diagnosis, as this will direct our medication choice going forward.

These are exciting times for both renal and cardiovascular care, as we now have medications that are protective. I suspect the SGLT2s will soon be regarded as drugs for reno- and cardioprotection, with glucose lowering as a side effect!

Developments that will impact your practice.

29 Aug 2025