We are not all mental health professionals. Diabetes practitioners are of many disciplines and specialities, and we mostly and necessarily focus on the physical aspects of the condition. However, as I recently commented in this Journal, today it is non-negotiable to be working in diabetes care and not consider the emotional and psychological effects of diabetes as well as the physical issues (Walker, 2019).

Enquiring about feelings and having a mental health professional with knowledge of diabetes in every diabetes care team are also the subjects of “It’s Missing”, a current campaign by Diabetes UK, based on their comprehensive report Too Often Missing (Diabetes UK, 2019a) Hence, just as with any other evidence-based developments, we may all need to extend our practice, in this case to ways we can help with emotional and mental health issues, even if these are not our specialist area.

Reassuringly, as the Diabetes UK (2019b) Guide to Diabetes and Emotional Health points out, everyone can help by simply acknowledging that diabetes has an emotional dimension, even if that is the full extent of their confidence in addressing the matter.

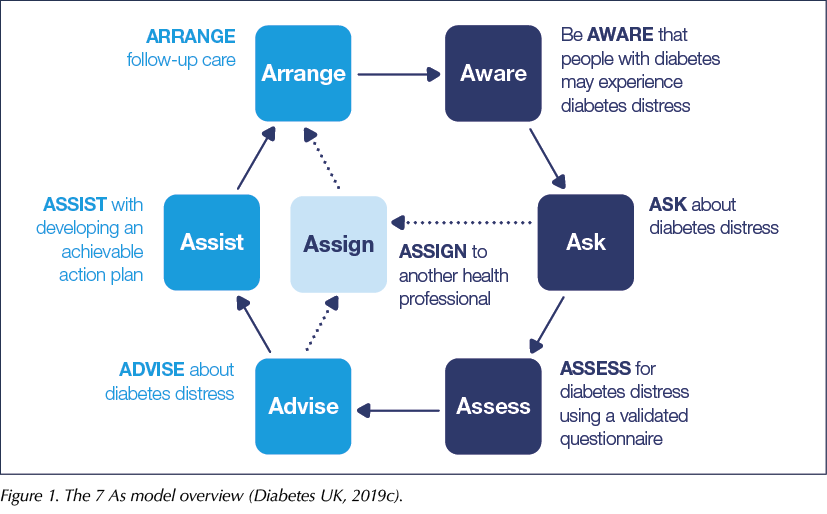

The “7 As” model (Diabetes UK, 2019c) is a way of incorporating enquiry about someone’s emotional health into diabetes healthcare encounters, and a structured way to approach what help you yourself can offer and what aspects you might need to consult with, or refer to, other specialist colleagues for their expertise. It is meant to be a flexible model that you can adapt to your personal practice level, rather than a “must-do” or a target to meet. It also offers a way for every clinical staff member to do at least the minimum in relation to promoting and supporting emotional health.

Background to the 7 As model and the Diabetes UK Guide

Originally, a 5 As model was developed in America for healthcare professionals supporting people with smoking cessation, with considerable success. The model has subsequently been adopted in many other countries, including Australia (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2019). The authors of the original Australian Diabetes and Emotional Health Handbook, which was adapted to create the present Diabetes UK Guide, adopted the model, with two new additions, to give a similar structure for enquiry and assistance with emotional health in diabetes.

In addition to the original 5 As, namely Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist and Arrange, there are now be Aware and Assign. These new “As” reflect the need, respectively, for ongoing attention and looking out for emotional issues, and recognition that acting on the issues identified might be outside a particular clinician’s scope of practice or confidence level.

The 7 As model overview is shown in Figure 1. The model is essentially a circle, the path of which can be followed by those clinicians who are able to undertake all the As. However, there is a “shortcut” for those who need it: a pathway for support by other health professionals whilst still keeping in touch with the individual being referred.

The 7 As in detail

Figure 1 shows the model components, grouped by colour. There are three “core” As, shown in dark blue. These are components that, ideally, every clinician can seek to implement.

Be Aware

This means keeping in mind that, for anyone, living with diabetes has an emotional context, regardless of whether this is causing any problems. It also means that demonstrating awareness of this in every routine encounter (and ideally acute encounters too – but that is an article for another day!) is desirable. No-one is suggesting that all healthcare professionals need to become walking encyclopaedias of the emotional effects of diabetes, but being aware can influence one’s approach, which will in turn bring benefits to people living with the condition.

Using Be Aware in practice

The best way to do this is to have a read of the Guide (Diabetes UK, 2019b), either in its entirety or choosing chapters that resonate with your experiences in practice, so that you can gain more insight, including, for example, on how to respond to “passing statements” or enquiries, or your sense that something is wrong but you cannot quite identify what.

Ways to respond include reflecting on any feelings or emotional context that the person with diabetes refers to, either verbally or non-verbally. Your awareness can be demonstrated by reflections such as, “It sounds as though you’ve had a hard time lately with your diabetes”, or a question such as, “How do you feel about your diabetes at the moment?”.

Your awareness can also be demonstrated by your use of language generally. Many examples of positive language to use are given in the Language Matters statement (NHS England, 2018), which is included as an appendix to the Guide.

The more familiar you are with the topics about specific diabetes-related emotional conditions, the greater the range of other awareness questions and prompts you can use. For example, if you wonder whether someone is struggling with an issue, you can confidently say, “Did you know we can assess and help people specifically for fear of hypoglycaemia/diabetes distress/eating problems?”. This can then open up the conversation helpfully, even if you may not be the person to take any action forward.

In addition to the specific topics in the Guide, chapters 1 and 2 cover communication and engagement, and what it is like to live with diabetes. These chapters offer information and awareness-raising at a general level, also relevant for all clinical encounters.

Ask

Ask has three important features. Firstly, as simple as it sounds, asking about someone’s emotional state as part of a routine review can add very little time to a consultation but make a big impact. As the Too Often Missing report says, people with diabetes are rarely asked specifically about their feelings about the condition (Diabetes UK, 2019a).

Secondly, if you notice any sign of emotional conditions, such as anxiety, fear of hypoglycaemia or diabetes distress, ask about them. Thirdly, ask follow-up questions related to the answers you receive to your initial enquiry, so as to explore a person’s needs further and work out an action plan of who and how to address them.

Using Ask in practice

Becoming familiar with the different topics and ideas for what and when to ask, which are contained in the Guide’s specific chapters, will help you to incorporate your way of asking about emotional issues. For example, on the topic of psychological barriers to insulin use, it is suggested to ask, both routinely at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and/or when someone expresses concerns, “How do you feel about going on to insulin, now or in the future?” or “What specifically are you worried about?”.

Assess

Assessment is key to indicating whether or not a problem is present and/or for exploring treatment and support options. In addition to assessing through questions and sensitively exploring issues raised in conversation, there are assessment tools for both routine monitoring and specialist conditions included in the Guide. These tend to focus on one inventory for each, chosen because it is accessible, evidence-based and frequently used. This is so you can be confident and become familiar with using it if you need to. However, it is important to know that other assessment inventories are available, and you or your local area may use or recommend others. The Guide is not prescriptive, except in Chapter 1, to emphasise the importance of assessment and having a clear policy about what and how assessment by questionnaire is used.

Using Assess in practice

One way of incorporating assessment into your practice could be using a general inventory on a routine basis, by inviting people to complete the questionnaire prior to their clinic visits, or being offered it on arrival. Successive scores will, like other medical parameters, give a picture of any changes and an indication of areas of specific concern. For example, high-scoring items on the PAID (Problem Areas In Diabetes) scale can highlight which areas are causing problems, and thus give a steer to the consultation conversation.

Specific questionnaires, for example mSCOFF for eating problems, can be used if your “Ask” has resulted in someone raising concerns about eating. Bear in mind that such questionnaires can not only highlight a need to be addressed but also reassure that the concern is within expected limits, both of which can be helpful to know.

All the questionnaires in the Guide include instructions for what the results mean, and they are also downloadable so you can become more familiar with them. If you are unfamiliar with routine or specialist assessment in practice, it may be that using these questionnaires could be the subject of your team meeting, with perhaps an invited mental health professional or psychologist to help make decisions on who, how and when to use them.

Advise

The next A is shown in lighter blue in Figure 1. This colour shows components that arise from the three core As. Taking action on these may depend more on your particular expertise, confidence or experience, although, using the Guide to help, these can of course be developed.

Advice can be general or specific. For example, you can give general advice that diabetes can bring emotional or psychological issues and that assessment and enquiry for these may be done in the same way as assessment for physical conditions. In the case of specific conditions being identified or suspected, letting the patient know that these can be treated or managed and giving information and advice about strategies are also part of advising.

Using Advise in practice

Each chapter of the Guide shows what advice you might give in relation to that particular issue, as well as the importance of making a joint plan about next steps, should this be necessary. This includes advice for physical as well as emotional issues. For example, in relation to fear of hypoglycaemia, the advice includes to explain that keeping blood glucose levels higher in an understandable attempt to avoid hypoglycaemia may have longer-term health consequences. In this way, you can see how the emotional and medical aspects of diabetes can be addressed together.

In addition to the practical advice, advising also includes giving reassuring and positive messages about conditions; for example, in relation to depression, you can explain that this is common and treatable, and that its proactive management can in turn help improve general diabetes management or self-care. Giving these messages in a non-judgemental and kind way also helps to remove or prevent stigma associated with psychological or emotional conditions alongside diabetes.

Assist

This relates to helping someone create an action plan, which can include actions by yourself on their behalf, such as referrals or provision of specific sources of further information.

Using Assist in practice

The action plan needs to be based on what has emerged from other As such as Assess and Ask, and, importantly, should be achievable and realistically time-scaled. For example, some referrals may take longer than others to be actioned, or a person may wish to prioritise self-help from independent sources or peer support, so you may agree a shorter-term plan for the interim period.

The extent to which you can assist someone once an issue has been identified may well, and understandably, be limited by your present experience, confidence or knowledge. If this is the case, being clear about this and managing expectations is important. Reflecting on the times you feel less able to assist someone could also act as professional or team development, to create new ways to help in future or plan for new learning on these specific areas.

Arrange

This A relates to arranging follow-up contacts to ask about the person’s progress and action plan review. This might be “as usual” – for example, routine appointments – or temporarily different, depending on the circumstances. It may also involve different types of communication.

Using Arrange in practice

Arranging further contacts is very familiar in clinical practice. A possible difference when dealing with emotional or psychological issues is to consider arrangements for extra contact, perhaps by email, telephone or more frequent or longer face-to-face visits, for a period of time, to reflect on the progress of an action plan, to seek specialist support or to repeat assessment questionnaires.

A vital part of arranging next steps and providing opportunities for enhanced contact, where needed, is to demonstrate to the person with diabetes that emotional care is as important as their physical care, and also to show sensitivity to issues at a time when people might feel particularly vulnerable or less able to cope.

Assign

The final A is shown in very light blue in Figure 1. This involves referral to a colleague of your own or a different discipline, specialist team or centre, for issues and problems that are outside your own expertise, knowledge or confidence. It also involves acute referrals when you believe someone is at imminent health risk, either emotionally or physically. Examples of common referrals for emotional issues outside of diabetes care include psychologists, psychiatrists or the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service. Occasional referrals may also be needed to mental health crisis teams or specialist eating disorder teams, depending on the results of any assessments you have made.

Using Assign in practice

Referrals are another very common practice for diabetes clinicians, albeit often to other medical specialists such as podiatrists or ophthalmologists. In order to assign in relation to emotional or psychological practitioners, you will first need to know what is available in your locality or region. If this is not already known, discussing with your clinical team, creating a local strategy for referrals and networking with colleagues can provide a valuable and prompt pathway for when you need it.

It may be that, in common with many areas, there are limited specialist services for emotional, psychological or mental health problems in your locality, especially for people with diabetes specifically. The Diabetes UK It’s Missing campaign is highlighting this. However, a further positive outcome of the greater awareness, assessment and enquiry by individual clinicians, in the ways described here, could make a useful contribution to data collection for making a case for commissioning. In this way, everyone can make a difference.

In Figure 1, you can see there are direct links to Assign from both Ask and Advise, but please note that choosing Assign does not bypass Assist! The 7 As model strongly recommends that the referring clinician continues to be in interim contact with the individual whilst assignment or other arrangements are made, and during any course of treatment or therapy. It is also recommended to try to be in contact with the service or practitioners you have referred to, where this is possible.

Other supporting resources

Summaries

The Guide includes a link to download concise 7 As summaries for all the main emotional distress issues covered in detail in the chapters. These summaries include the following:

- Diabetes distress.

- Fear of hypoglycaemia.

- Psychological barriers to insulin use.

- Depression.

- Anxiety disorders.

- Eating problems.

These are available to download as a single PDF at: https://bit.ly/2X1RDp7.

If you have these to hand in your consultations or other encounters, using the headings and bullet points, you can easily incorporate the aspects you can deal with into practice, and also see how you can refer or continue to support someone with the particular identified issue.

Leaflets for people with diabetes

A series of leaflets covering the main emotional conditions in the chapters are also available to download (Figure 2).

These can be distributed individually during a consultation, kept in waiting areas, displayed on notice boards and used in education or peer support sessions locally. They include the following:

- Adjusting to life with diabetes.

- Diabetes and anxiety.

- Depression and diabetes.

- Diabetes distress.

- Eating problems and diabetes.

- Fear of hypos.

- Peer support and diabetes.

- Worries about insulin.

These can be downloaded via links on the home page of the Guide.

Chapters

Each condition-specific chapter mentioned above goes through how the 7 As apply specifically to the emotional issue under discussion, as well as providing relevant ideas for questionnaires that can be used for assessment. It is worth an additional reminder that the questionnaires cited are not exhaustive and that your specialist diabetes team or local psychological service may provide or use others alongside or instead of these.

Case studies

The chapters also contain case studies which look in detail at how individuals experiencing these issues can be supported using the 7 As model. You could use these to help work out how they could apply to similar situations you come across in your own practice.

Conclusion

This article has described the 7 As model for supporting emotional health in adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and given ideas for how the model can be implemented by any clinician, whatever their current level of expertise. It has also shown the extent of resources offered by the new Diabetes UK Guide to Diabetes and Emotional Health. These can be used to benefit people with diabetes and clinicians alike.

NHS England to allow weight-loss injections for prioritised patient cohorts from late June.

5 Apr 2025