2016 saw the launch of the Sugary Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL), a Government policy aiming to address the childhood obesity epidemic. But is it working? And what might come next?

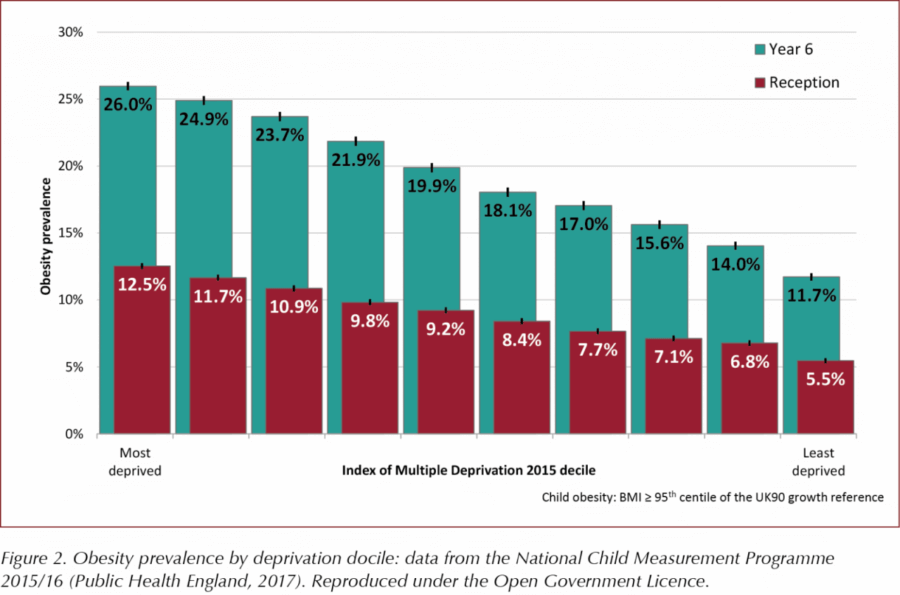

Current trends are far from encouraging with regards to meeting the Government’s June 2018 announcement of “a national ambition to halve childhood obesity and significantly reduce the gap in obesity between children from the most and least deprived areas by 2030” (Department of Health and Social Care [DHSC], 2018). The most recent National Child Measurement Programme data show, at best, ongoing plateauing of childhood obesity in England (Public Health England [PHE], 2017; Figure 1). In 2016/17, the prevalence of obesity in children in reception increased from 9.3% to 9.6% and, for children in year 6, it remained fairly stable at 20.0%. Combined overweight and obesity prevalence rates are over 26% in reception and 34% for 11–15-year-olds.

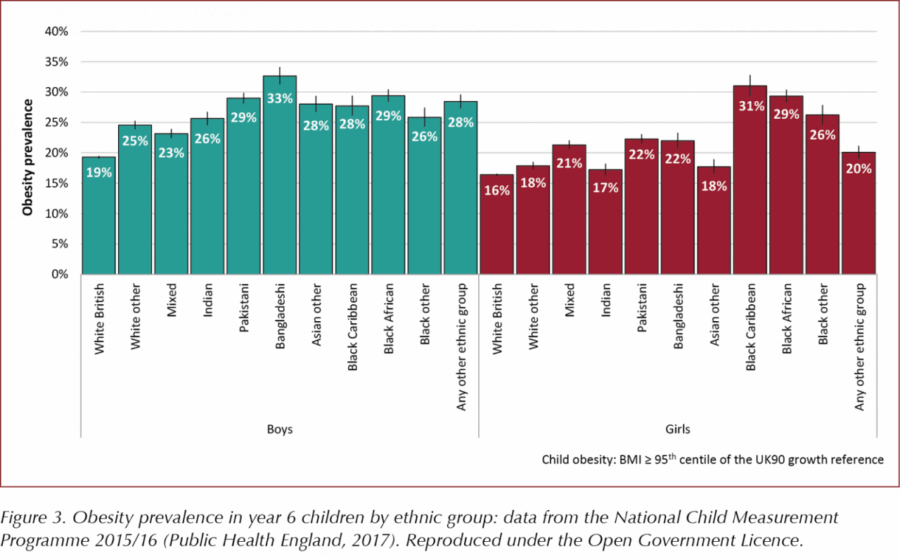

It is of concern that we are seeing a widening of the deprivation gap. Obesity prevalence for children living in the most deprived areas was more than double that of those living in the least deprived areas for both reception and year 6 (PHE, 2017; Figure 2).

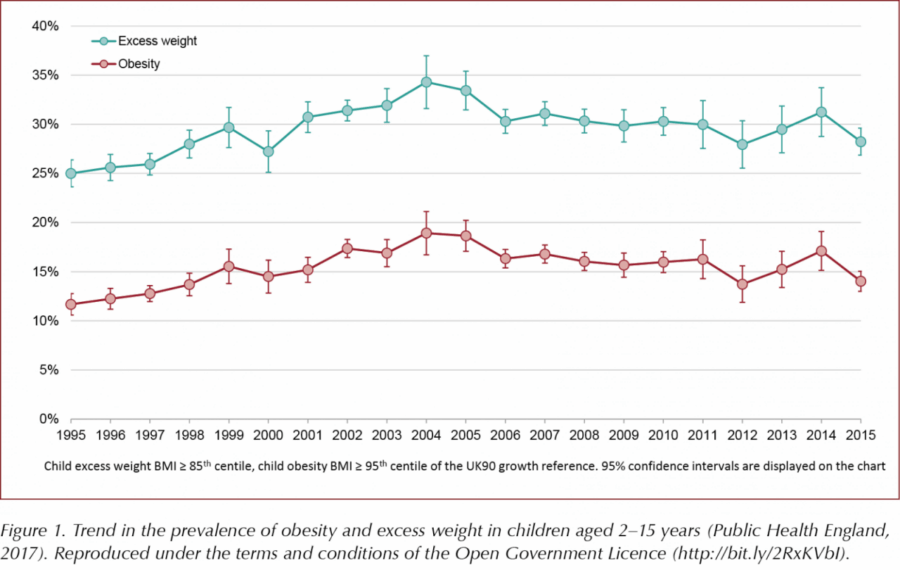

Marked differences are also noted between ethnic groups, but childhood obesity intervention research is yet to tailor programmes to address ethnic factors (PHE, 2017; Figure 3). Regarding childhood type 2 diabetes, a 2015/2016 UK study showed that incidence in children aged <17 years was 0.72 per 100000 per year. Whilst far less common than type 1 diabetes, the number of cases continues to rise, particularly among girls and South‐Asian children (Candler et al, 2018).

There is great alarm around the strong tendency for obesity to track from childhood into adulthood, with forecasts that the already woeful statistics on obesity-related type 2 diabetes are set to worsen. But concern extends beyond the impact on metabolic conditions, such as diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, to tooth decay, mental health and the array of conditions associated with physical inactivity, such as lung and musculo-skeletal complaints. Current conservative estimates put NHS obesity-related costs at £6.1 billion per year (DHSC, 2018).

The 2016 Childhood Obesity Plan (COP) saw the announcement of the SDIL, a tax on drinks with higher sugar content. Industry was given a 2-year warning – the tax came into effect in April 2018 – to allow time for sugar-lowering reformulation to avoid paying the tax. This produced improvements to many soft drinks, and the lack of industry uproar reflected the public’s grasp of the “toxic sugar” message and agreement with reformulation. Indeed, contrary to industry fears of profit hits and job losses, public demand for healthier food and drink continues to increase.

The SDIL was not the plan’s only action; it included an industry challenge to voluntarily remove 20% of sugar from common children’s foods by 2020, with a 5% reduction in year one – plus threat of legislation if progress is poor. Whilst Kellogg’s might have slashed up to 40% of sugar from some kids’ cereals and Yoplait have dropped over 13% sugar, wider reformulation has been patchy, and the 5% drop has not yet been achieved. Indeed, industry has voluntarily managed just a 2% reduction in sugar content, in line with previous poor outcomes from non-mandatory targets of the 2011 Public Health Responsibility Deal.

June 2018 saw the launch of Chapter 2 of the COP (DHSC, 2018), which included the following proposals:

- Re-examination of fruit juice and milky drinks (initially excluded from the SDIL because of complexities around their nutritional merits despite potentially harmful levels of sugar) and addressing how energy drinks are targeted at children.

- Consideration of tax breaks for healthy foods if the voluntary reduction programme stalls. PHE have produced industry guidance in the Sugar Reduction Programme to set voluntary targets for milk-based drinks and juices as well as set targets for portion sizes and to promote diet drinks.

- Consistent calorie labelling is due to be mandated for restaurants and takeaways, as well as front-of-pack food labelling.

- Consultation on the introduction of a 9 p.m. watershed on television advertising of foods high in fat, sugar or salt (HFSS), plus a review on whether current self-regulated advertising rules need to be tightened.

- Ban price and location promotions, such as BOGOF (“buy one, get one free”) and confectionery at checkouts, store entrances and aisle ends.

Proposals also include showcasing local area success stories and building on the engagement of schools by, for example, strengthening nutrition standards for food catering and promoting national adoption of the Daily Mile (an initiative to encourage children to run or jog for 15 minutes each day in their primary or nursery schools).

Health Secretary Matt Hancock pledged in November 2018 to shift focus from “single acute illnesses to promoting health of the whole person… and to targeted predictive prevention.” Whilst any reversal of the recent decimation of public health funding is welcomed, prevention approaches to childhood obesity will not be enough. Established obesity requires multicomponent structured support and cannot be wished away with glib remarks to “just eat less and get moving”. We have yet to see any coherent development of child obesity treatment services, with a postcode lottery of scarce services, and some areas offering no child obesity services at all. Meanwhile, the important health benefits of physical activity (PA) initiatives are still, unfortunately, being conflated with unrealistic expectations of weight loss. This gives false perceptions that obesity is being addressed and potentially jeopardises engagement in ongoing PA participation when anticipated weight loss fails to materialise, whilst genuine PA benefits go unnoticed (Pryke, 2018).

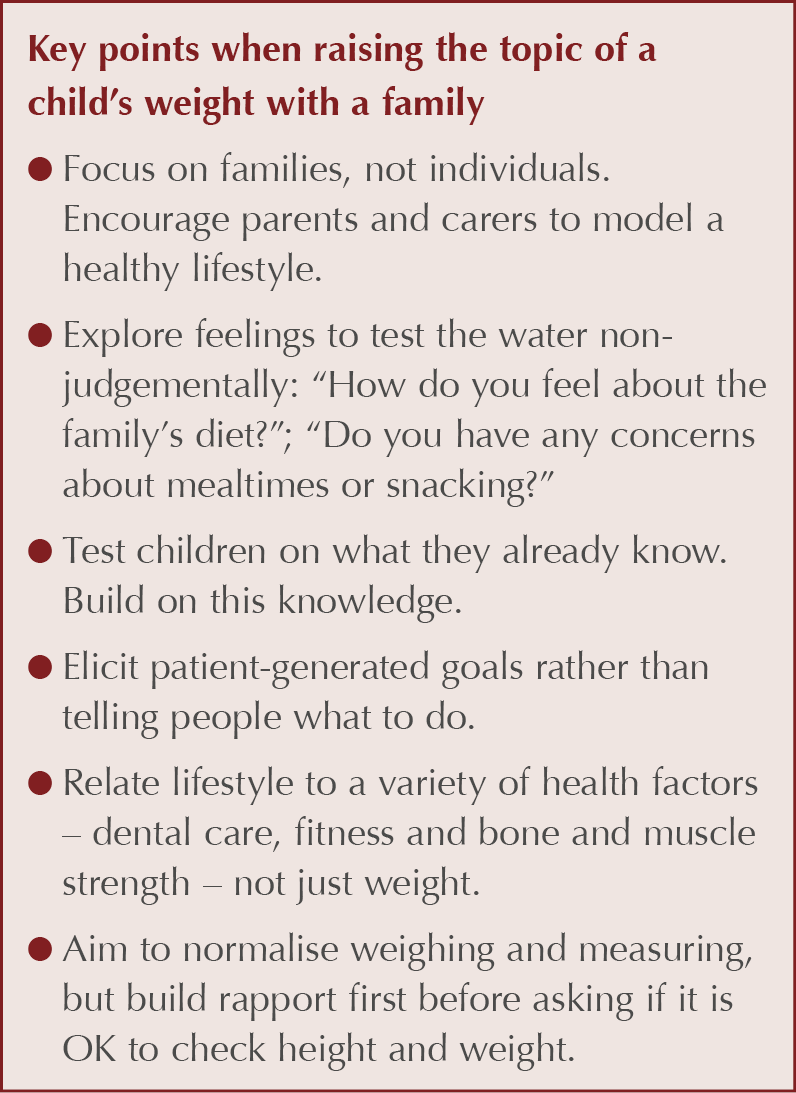

Primary care clinicians have valuable roles in raising awareness of weight and its impact on an array of related health problems, signposting families to useful resources and giving ongoing support (see Box 1). Obesity is a chronic disease and, in line with other chronic diseases, requires regular supportive review and appropriate interventions. Long-term solutions remain elusive, but increasing collaboration between the food industry, health workers and individuals will help families to adopt greater responsibility for their health and lifestyle choices.

SURMOUNT-5 trial pits tirzepatide against semaglutide, plus behaviour change support, for weight loss.

12 May 2025