Since my last editorial, in which I made mention of the draft guideline, the full American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) consensus guideline on the management of type 2 diabetes has now been ratified and released (Davies et al, 2018).

I have to say I believe these guidelines are a huge leap forward in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. They take into account the latest evidence from the cardiovascular (CV) outcome trials (CVOTs) and firmly place sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue therapies as the second line when weight loss or the presence of established CV or renal disease are the primary concerns. Furthermore, they suggest that the choice within class is to be based on proven CVOT positivity. The only aspect, for me, that is not highlighted within the document is the treatment targets for frailty, as there is no specific advice on the de-escalation of therapy in this group.

The previous ADA/EASD guideline allowed for any drug choice after metformin; however, this still led to confusion amongst healthcare professionals who were unsure of the classes and, therefore, delays in appropriate escalation of therapy. Conversely, the NICE (2015) guidance gave a more limited choice after metformin and put the GLP-1 analogue class as a clear fourth-line option.

The new guidance suggests treating the person and his/her individual profile and, as I have discussed in previous editorials, treating more than just glycaemia (see Figure 1). The recommendation is to establish the presence of CV or renal disease and, if these are present, make them the priority when choosing the therapy.

If atherosclerotic CV disease or chronic kidney disease are not present, the priorities are weight reduction (or prevention of weight gain) and avoidance of hypoglycaemia. Finally, if cost and affordability is the major issue to the health system, options are available in this space. The inference within the body of the full consensus guide is that cost should only be the primary factor for treatment choice in developing countries.

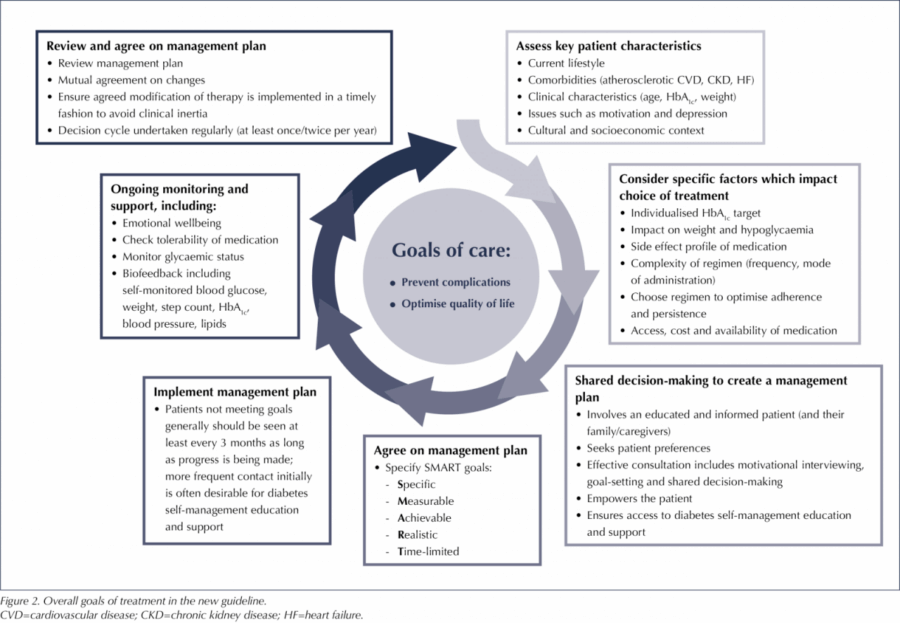

The overall goal of care is to prevent complications and optimise quality of life (Figure 2). The agreement of treatment targets and management plans, along with SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-limited) goals, is recommended, and this firmly puts the person with diabetes at the heart of any decision-making.

It is refreshing to see that the co-chair of the editorial team for these guidelines was our own Professor Melanie Davis, from the Leicester Diabetes Centre, with several other UK-based specialists being part of the panel or reviewers of the guideline.

This consensus statement has now put a question over the appropriateness of the current NICE (2015) guidance. Dates for the review of this are yet to be set and are likely to be at least a year away. If delayed for too long, this will put us at a distinct disadvantage to the rest of the developed world.

ADA/EASD consensus report

The full, open-access guideline is available to download from Diabetologia at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4729-5

Developments that will impact your practice.

22 Dec 2025