The impact of a consultation can be disproportionate to the time it takes. Many years after diagnosis, people with diabetes can often still remember their first clinical encounters – both helpful and unhelpful advice can shape their attitudes to and feelings about diabetes management for the rest of their lives. It all comes back to communication and interpersonal skills: the key ingredients of clinical consultations (Alzaid, 2014).

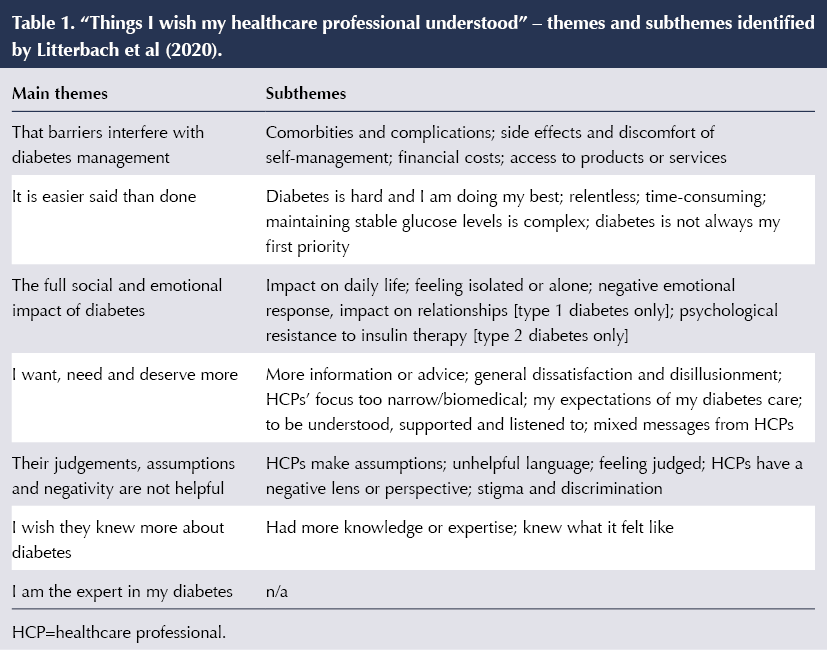

We asked Australian adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes an open-ended question: “What do you wish your healthcare professionals understood about living with diabetes?” (Litterbach et al, 2020). The responses of more than 1000 people offer important insights. The main themes of these are summarised in Table 1. Overall, participants’ wishes were consistent with clinical guidelines and most form part of the person-centred model of care that has been promoted for several decades (Rathert et al, 2013).

While some healthcare professionals have made small, positive changes toward person-centred “listening” (Stuckey et al, 2015), fewer have integrated psychological care within their clinical practice. The much needed shift from a biomedical model to this holistic care model has indeed been slow (Speight et al, 2019). This may partially explain the lack of improvement in diabetes outcomes over the past two decades despite many advances in diabetes treatments and technologies (Edelman and Polonsky, 2017).

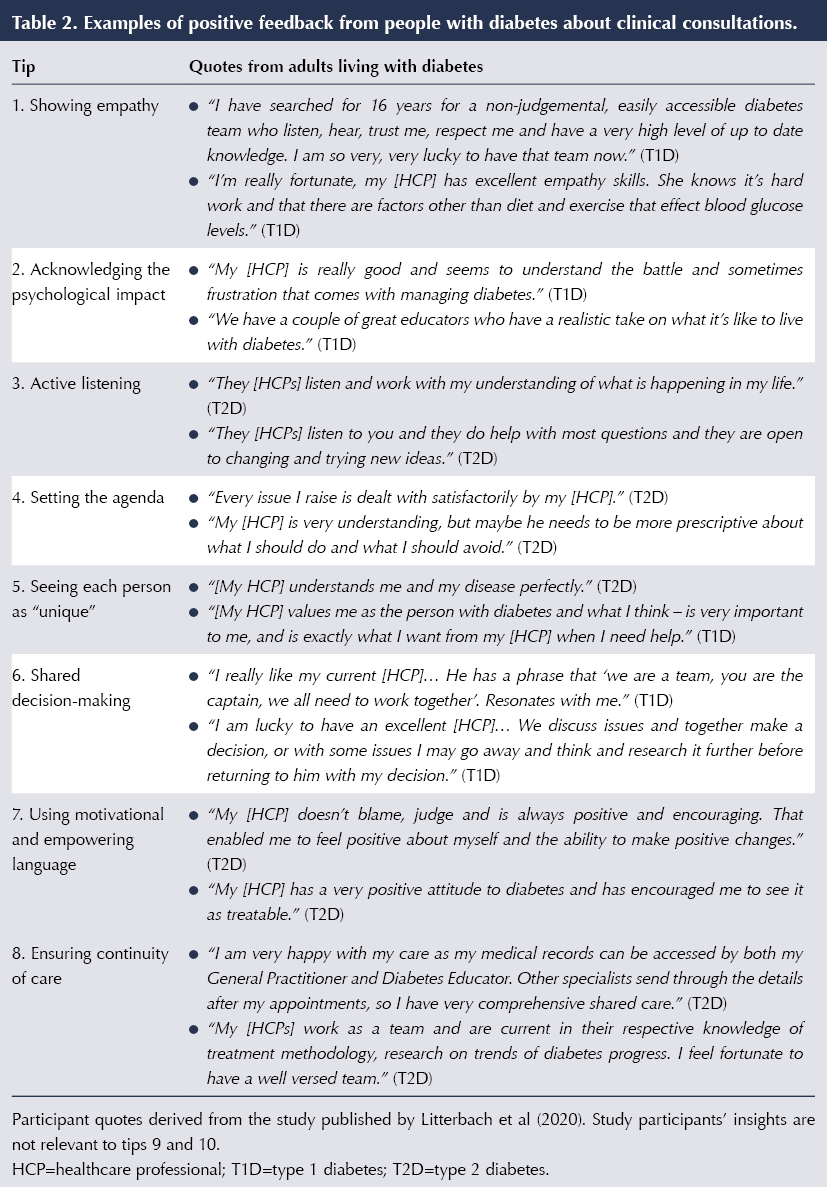

The qualitative responses from our research (Litterbach et al, 2020) inform ten tips for healthcare professionals to improve clinical consultations with people with diabetes. Many of these may seem to be common sense, but it is clear that they are not universally adopted or sustained in clinical practice. These tips may offer you an opportunity to reflect on your own practice and to consider the simple changes you and your teams can make to achieve more effective and satisfactory consultations – both for people with diabetes and for yourselves. Table 2 includes quotes from people with diabetes reflecting on positive experiences with their healthcare professionals, related to the tips.

Tip 1: Showing empathy

This is the first tip for a reason: it is central to holistic care. What is empathy and how can we show empathy without becoming emotionally attached? Empathy is a cognitive rather than an emotional form of understanding the person’s experiences, feelings and perspectives (Hojat et al, 2015). As such, it is different from sympathy. Being empathic does not require the healthcare professional to experience and introspect the person’s emotions, as this could divert the focus from the person’s experience to the professional’s own.

Using open-ended questions builds rapport and trust, enabling exploration of the person’s experiences and better information-sharing. Healthcare professionals are then better informed about the person’s needs and better able to promote effective treatment options.

Tip 2: Acknowledging the psychological impact of living with diabetes

Participants expressed the wish for their healthcare professional to acknowledge the psychological burden of living with diabetes (Litterbach et al, 2020). Normalising this burden can help the person feel less alone or isolated. Responses such as “That’s understandable. You know, many people with diabetes feel that way too” may help to reduce feelings of, for example, guilt and blame, when they realise that what they feel is not uncommon (Fisher et al, 2019).

Diabetes UK’s Diabetes and emotional health is a free, online practical guide for healthcare professionals to support adults with diabetes experiencing common emotional problems, such as diabetes distress or fear of hypoglycaemia. This guide has many practical tips on how to respond when people with diabetes share their emotional struggles and what questions to ask to further explore their support needs.

Tip 3: Active listening

Closely related to empathy and acknowledging emotional impact is “active listening”, which includes attending to both what a person says and how they say it. Although this may seem one of the easiest skills, many healthcare professionals struggle to give the person space to express themselves. This can be because they fear it will lead to long monologues or because they feel ill-equipped to respond to visible distress. But is this fear substantiated? On average, a patient talks for about 90 seconds about their concerns when invited to do so (Langewitz et al, 2002). They are, in general, well aware of the limited consultation time and they do not expect long consultations (Hajos et al, 2011; Mazzi et al, 2016).

Active listening creates opportunities for the person with diabetes to trust and feel confident to confide in you without fear of judgment or blame. An open and honest conversation about the person’s current issues or barriers (e.g. their reasons for not taking medications) will inform ways to overcome these, leading to more effective and sustainable diabetes management plans. Developing active listening skills requires practice. During your next consultation, refrain from interrupting a person while they speak, and show signs (eye contact, nodding) that you are paying attention to what they are saying.

Tip 4: Setting the agenda and agreeing today’s priorities

In a large international survey, most healthcare professionals considered it helpful for people with diabetes to prepare questions prior to the consultation (Holt et al, 2013). However, agenda-setting is not yet routine in clinical consultations. When it is, healthcare professionals interrupt the person after just 11 seconds on average, usually with a statement or closed question (Singh Ospina et al, 2019), which shut down the conversation.

At first, people with diabetes may be surprised to be invited to set the agenda as it has not been part of their past experience, or they may not have a specific agenda. That is fine; it is about offering the opportunity. If they do not take it up now, maybe they will at the next consultation, after they have given it some thought.

If agenda-setting is not part of your routine practice, consider how you could try this. If there are too many agenda points, make a plan that discusses the highest priorities today, and agree how and when to address issues not covered at this time. Between consultations, you could refer the person to online or written resources. This will also help them to formulate their needs and concerns, and potentially their own ideas about what may help.

Tip 5: Seeing each person as unique and not a “textbook case”

Participants in our study felt their healthcare professionals assumed that medical textbooks provide a blueprint for achieving ideal diabetes outcomes, such as an HbA1c in target (Litterbach et al, 2020). Similarly, healthcare professionals often ask, “Why are people with diabetes not motivated to follow my recommendations?” This may be because:

- They have experienced that following recommended guidelines does not guarantee the expected outcomes.

- Diabetes requires a predictable routine that is a huge effort, often unsustainable, and is not a one-off but all day, every day.

- Each person with diabetes has different needs and experiences, and wishes to be recognised for their own expertise in managing this condition.

- Hormones, other medications, sleep quality, weather, incidental exercise, and the list goes on, all impact glucose levels.

While evidence-based clinical recommendations are essential and provide directions for what works, there has to be a realisation that one size does not fit all when managing a chronic condition. Personalised care leads to better outcomes because these fit better with the person’s beliefs, needs and concerns.

Tip 6: Shared decision-making

With today’s plethora of diabetes management options, including a range of technologies, medications and dietary approaches, people have choices and may have strong preferences. Some participants highlighted that they are the expert in their own diabetes and that they often come to consultations knowing more about the latest advances than their healthcare professional (Litterbach et al, 2020). Others rely on their healthcare professional as “the expert”, and want to be given detailed guidance and plans.

Shared decision-making is a shift in power from the healthcare professional controlling the interaction to a collaboration between the healthcare professional and the person with diabetes. It is a process of sharing information and expertise: the healthcare professional providing accessible and evidence-based information about available treatment options, costs and benefits; and the person with diabetes sharing what matters to, and works for, them.

Tip 7: Using motivational and empowering language

There is consistent evidence that self-efficacy is a key determinant in behavioural change. Yet clinical conversations are still highly focused on risk reduction, with an emphasis on what the person with diabetes “should avoid” or what they “should be doing better”, rather than identifying where they are already doing well and building upon that positive foundation. In our study, some participants reported their healthcare professional(s) to be very supportive and encouraging, or they appreciated their positive outlook (Litterbach et al, 2020).

Healthcare professionals are ideally placed to support people with diabetes to identify their strengths and skills, which can enhance their empowerment (Kristjansdottir et al, 2018). In this respect, NHS England’s Language Matters document is a practical resource for reflecting on the words and language that can empower and motivate people living with diabetes (Cooper et al, 2018).

Tip 8: Ensuring continuity of care

Diabetes care involves multiple healthcare professionals, each with their own expertise and perspectives. People with diabetes reported a lack of consistency in advice and messages, and in continuity of care (Litterbach et al, 2020). There was a desire for team-based care, with communication between all team members.

Higher continuity of care has been found to be associated with lower mortality rates (Pereira Gray et al, 2018). It is difficult to determine with certainty why this relationship would exist, but the authors speculated that trust (built over time) and open communication lead to greater disclosures, better tailoring of care to the person’s needs, and greater likelihood of optimal self-care and taking medications as recommended.

Tip 9: Taking small steps

When making changes in lifestyle and management, we often advise people with diabetes to go slow and take small steps towards achieving their short- and long-term goals. This advice is also helpful for healthcare professionals who want to enhance their consultation skills. Reflect on your current practice, consider what works and what you would like to change. Think about the changes you could make, what you would like to achieve, how and when. Then evaluate after a couple of consultations what has been going well and how to improve further next time.

Tip 10: Making consultations more satisfying for yourself

Working in a health setting and caring for others can, at times, be demanding and stressful. Many factors contribute to work stress; one is the quality of communication and interpersonal relationships in the work setting. When experiencing frustrations, and perceiving that this is because “patients are not motivated”, take a step back and reflect on what the reasons may be.

Person-centred care benefits the individual with diabetes as well as the healthcare professional, and may reduce the risk of work burnout. Having a better understanding of the person’s perspective facilitates shared decision-making, and will very likely impact the person’s motivation to engage with the agreed action plan. This affects the therapeutic relationship, to the satisfaction of both parties.

Conclusion

These are ten tips, but they all come down to one central topic: communication, mutual trust and respect. These tips for more effective and satisfying consultations are proven and powerful. Most importantly, they are possible in your clinical practice today.

Acknowledgement

The authors are supported by the core funding to the Australian Centre for Behavioural Research in Diabetes provided by the collaboration between Diabetes Victoria and Deakin University.

Shift towards more personalised treatment recommended in draft guidance.

20 Aug 2025