To date, support and advice via telephone has been incorporated into the daily workload of many nurse specialists and is an integral part of patient education and self-management. There appear to be many definitions of telephone support and advice services. Most publications have focused on telephone triage, which is defined as “an interactive process between the nurse and client that occurs over the telephone and involves identifying the nature and urgency of client healthcare needs and determining the appropriate disposition” (Rutenberg and Greenberg, 2012).

Telephone consultations occur in a range of practice settings and are increasingly part of the care of chronic conditions such as diabetes. Evidence suggests that such services are highly beneficial to users (Hughes et al, 2002) but are undervalued and under-resourced by healthcare management, while healthcare professionals’ enthusiasm is tempered by concerns about medical risks (Car and Sheikh, 2003).

Study aims and objectives

In order to evaluate this aspect of the diabetes service, the diabetes nurse specialists in the Saolta University Health Care Group, in the West of Ireland, conducted an audit to evaluate telephone support offered to all patients with diabetes within a one-week period.

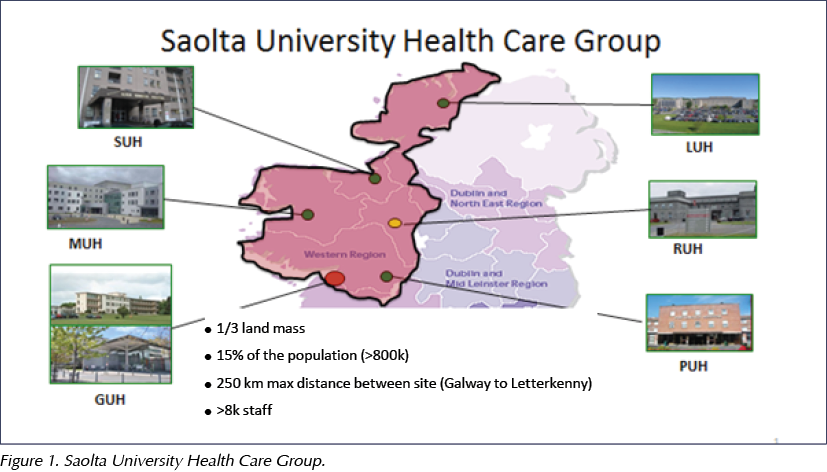

Saolta University Health Care Group serves the population of counties Galway, Donegal, Leitrim, Sligo, Mayo, Roscommon and adjoining areas in the West of Ireland, and serves a population of 703 684, which accounts for 15.3% of the national population (Figure 1). Over 70% of the community resides in rural locations. Each of the counties listed have diabetes units based in the acute hospitals, providing diabetes services to adult and paediatric populations, as well as clinical nurse specialists in diabetes working in integrated care, supporting diabetes education and care in general practice and community settings. The use of the telephone to support patients in their diabetes care and management between clinic visits has become a crucial aspect of the role of all diabetes nurse specialists, but concerns are often voiced about the poor recognition by healthcare management regarding this aspect of the service.

The diabetes nurse specialists in the Saolta University Health Care Group meet twice yearly to offer support, share experience and promote practice development. Through these meetings, discussions took place regarding the increasing demands on time of providing telephone support to people with diabetes between clinic visits. While it was acknowledged that this is a service highly valued by patients, it had never been quantified by the service or recognised by health service management.

The aim of this audit was to quantify the number of calls, the sources, the primary reason for the calls and whether a follow-up telephone call was required. The main objective of the audit was to identify the current resources utilised in providing and maintaining this service. This would also inform on the need for adequate resource allocation for future sustainability of this self-management support.

Method

All diabetes nurse specialists working in the Saolta University Health Care Group agreed to participate in an audit to capture information on the telephone support service. A paper-format audit tool was developed and agreed. The information was collected at the time of each call within a defined period of 1 week. Details included the caller information; whether the call was from a patient, carer or healthcare professional; the type of diabetes; the reason for the call; the call duration; whether a follow-up call was required; and the hospital and diabetes nurse specialist information.

The audit was conducted over five working days over a 1-week period in February 2017. All 29 diabetes nurse specialists caring for adults and children with diabetes in primary and secondary care in the Saolta University Health Care Group participated. Ethical approval was not required.

Results

The total number of calls occurring within the defined 1-week period was 1256, averaging 251 calls per day. The average call duration was 5 minutes, with 21.5 hours of diabetes nurse specialist time spent on telephone consultations. This equates to a diabetes nurse specialist whole time equivalent of 2.6 across the whole Saolta University Health Care Group catchment area.

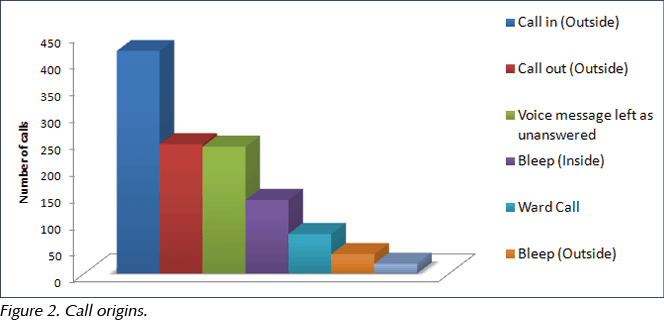

As shown in Figure 2, most calls originated from outside the hospital, with a substantial number of callers utilising the answering machine service and requiring a return call to follow up. Some diabetes nurse specialists allocate a specific time block during the day for answering external phone calls (for example, between 9 am and 1 pm Monday–Friday), particularly in centres with only one available diabetes nurse specialist, to facilitate the inpatient and outpatient clinic workload. Others, where possible, allocate a diabetes nurse specialist to this role during the day. This varies between hospitals depending on the available resources.

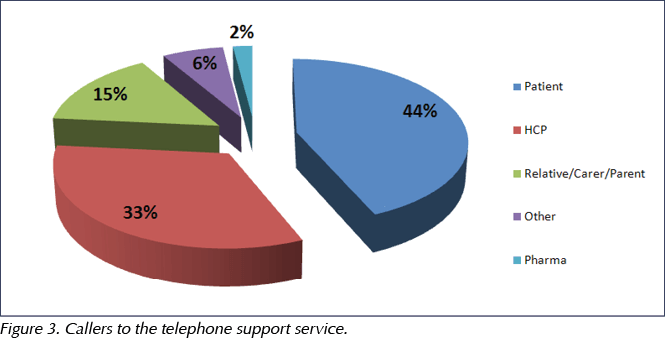

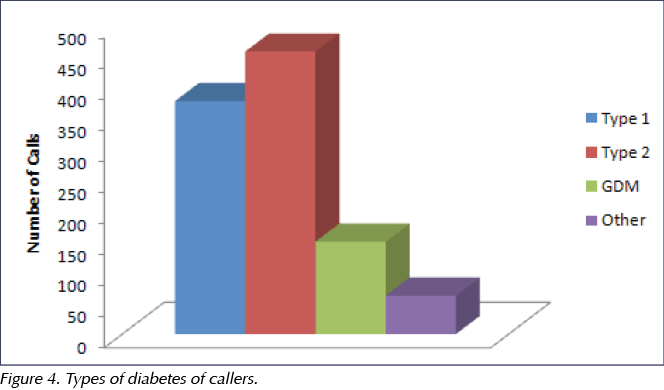

A high volume of calls (33%) were from allied healthcare professionals (Figure 3); however, the greatest proportion were from people with diabetes. Of these, most had type 2 diabetes (43%), followed by 36% with type 1 diabetes (Figure 4).

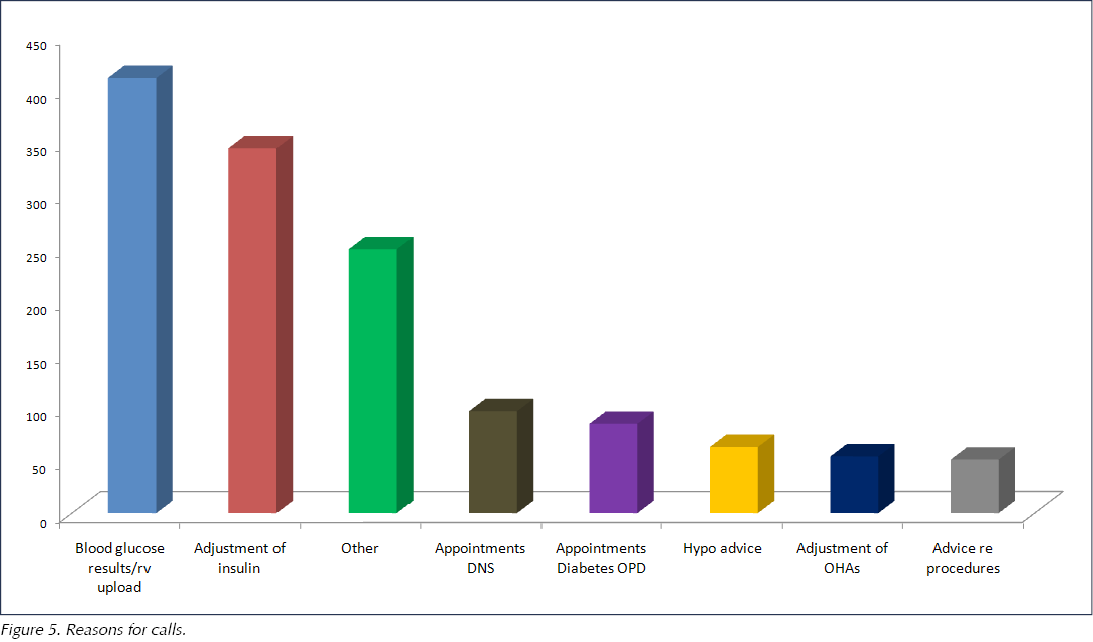

The main reason for seeking advice was concerns about blood glucose results (29%) and titration of insulin doses (25%; Figure 5). Other reasons identified included advice on hypoglycaemia (4%), medications (3%), planned procedures (3%), blood glucose meter issues (2.4%) and psychological support (2%). Many calls (13%) were requests for information regarding outpatient appointments.

Most patients who called (55%) required a follow-up telephone consultation, generally within 1–2 weeks.

Discussion

This audit demonstrates the high volume of telephone support calls to diabetes nurse specialists in the Saolta University Health Care Group. A study of people with rheumatoid arthritis demonstrated that, without telephone support from specialist nurses, 60% of patients would have requested a GP appointment (Hughes et al, 2002). Using the numbers from our audit, this 60% would represent 753 patient presentations to a GP service, hospital diabetes outpatient department or emergency department in one week.

A high volume of calls (33%) were from allied healthcare professionals, including GPs, practice nurses, public health nurses, and staff in nursing homes and community hospitals. This demonstrates the importance of the education and support provided by diabetes nurse specialists in linking the primary and secondary care interface and supporting integrated diabetes care.

Many calls (13%) were requests for information regarding outpatient appointments, which could be managed by administrative support, thus reducing and prioritising the diabetes nurse specialist workload. This highlights the need for administrative support, which is not currently available to most of the diabetes nurse specialists participating in the audit.

Telephone advice services provide a valuable contribution that focuses on promoting self-management strategies for people with diabetes, thereby reducing the risk of medical complications (Wheeler, 2017). They are highly valued by patients, and their cost-effectiveness has been demonstrated in other chronic conditions (Pope et al, 2005).

Borton (2009) suggests that documentation of telephone advice is less rigorous than face-to-face contact, with consultations relying heavily on clinical expertise and effective communication skills. There is also some evidence suggesting increasing levels of stress among nurses providing telephone support (Purc-Stephenson and Thrasher, 2010). Car and Sheikh (2003) suggest that staff training, standardised protocols and dedicated telephone time, with improved documentation to aid continuity of care, will help enhance the quality and safety of telephone consultations. They provide a suggested framework for recording such interactions and the necessary telephone communication skills required; this type of support may go some way to alleviate such levels of stress. Future research could focus on this aspect of telephone support services.

In Ireland, it is estimated that there are 225 840 people with diabetes (Balanda et al, 2006), and this number is predicted to rise to 309 200 by 2035 (International Diabetes Federation, 2014). This increased prevalence is also evident in gestational diabetes trends (Ferrara, 2007), further increasing telephone support requirements on existing resources.

The increasing demand for telephone support consultations highlights the need for specific guidance around providing telephone advice and support for people with diabetes. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Rheumatology Forum has recognised the changes in practitioner roles and variations in service provision, and has developed guidance for nursing practitioners (RCN, 2006), with telephone guidelines developed for other conditions such as Parkinson’s disease (Parkinson’s Disease Society, 2007).

It is recommended that the Health Service Executive capture and recognise the significant support provided through the use of telephone consultations by diabetes nurse specialists. It is also imperative that this support be adequately quantified through the use of key performance indicators and resourced appropriately. Specific guidance must be developed to encompass governance and legal issues, documentation and record keeping, and training and support for staff, with regular reviews and evaluation of the service to include audit and outcome measures (RCN, 2006).

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025