At diabetes camps, young people have the opportunity to meet and exchange experiences with other children and adolescents with their condition. Moreover, diabetes camps help young people to acquire independence in self-care, achieve better glycaemic control and improve their acceptance of the condition (Barone et al, 2016; Venancio et al, 2017, Weisserg et al, 2019).

Camps for young people with diabetes are common in countries such as the US and Canada. The camp format varies according to the specific goals. For example, day camps for children with diabetes and their parents might aim to provide family fun, while full-week camps, in which young people participate without parents’ supervision, might target improving independence in performing diabetes self-management.

Training for healthcare professionals who are willing to work in diabetes camps is commonly offered by organisations such as the American Diabetes Association (2012). Nursing staff are part of the healthcare team responsible for diabetes management and education in camps. To the authors’ knowledge, most camp staff are nursing undergraduate students who volunteer or take this role as a summer job. However, the specific role of nursing professionals in this context remains unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the role of nurses in diabetes camps, in order to inform guidelines on diabetes nursing.

Research procedure

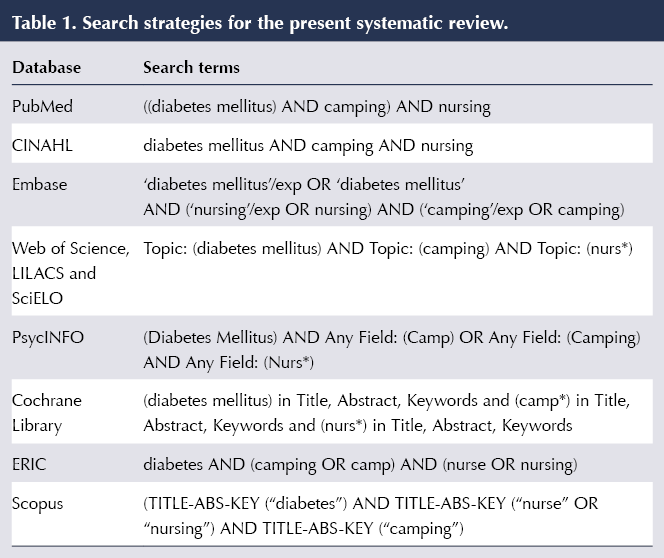

A systematic review was conducted based on the following research question (Moher et al, 2009; Hastings and Fisher, 2014): “What is the role of nursing staff in diabetes camps?” Specific search strategies were used for each of ten major health science databases, as shown in Table 1.

The search was conducted in April 2019 and included primary studies describing the activities carried out by nursing staff in diabetes camps. Studies on camps for children with chronic diseases other than diabetes were excluded. No limit for language or timeframe was applied. Two independent reviewers assessed the titles and abstracts of all identified studies and eliminated duplicates. The eligible studies had their full texts consulted. In order to reach consensus, the opinion of a third reviewer was sought in case of disagreement.

For data extraction and synthesis, the reviewers prepared a table in Microsoft Excel, consisting of the following items: authors; country and year of publication; study objective and design; characteristics of the nursing team; and nursing team role.

Identified studies

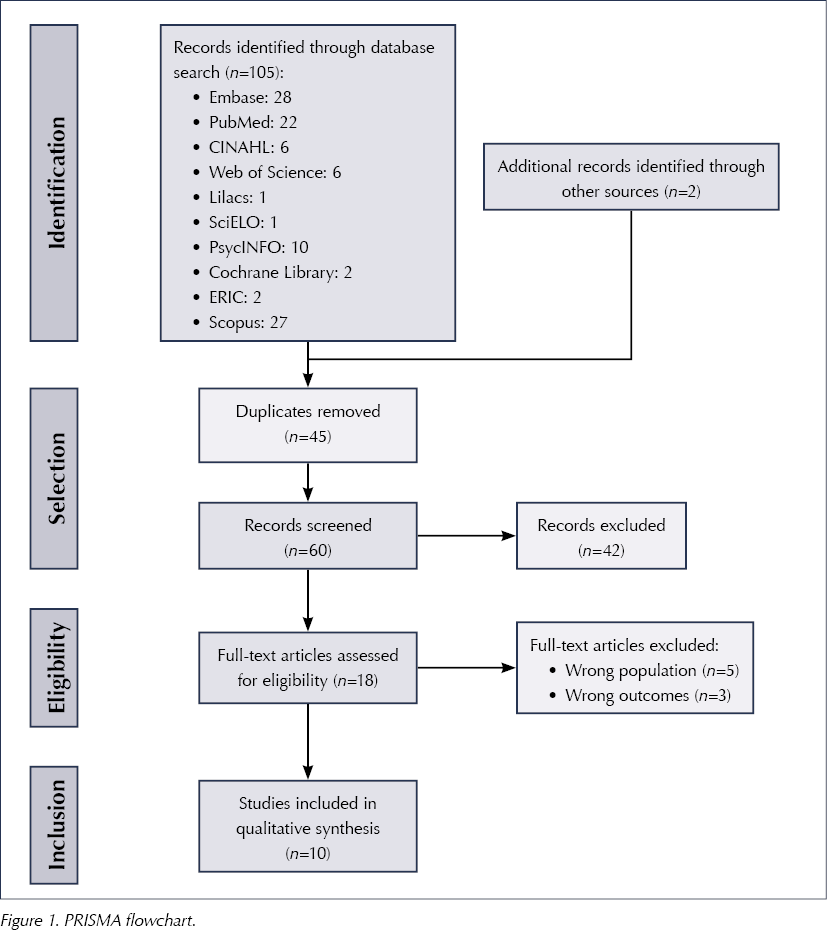

The search of the databases revealed 107 potential studies, and two other studies were included by unsystematic search of the reference lists. After reading the titles and abstracts, 18 full-text articles were analysed, and these gave a final sample of 10 studies for analysis. Figure 1 depicts the screening and selection for this review according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards (Moher et al, 2009).

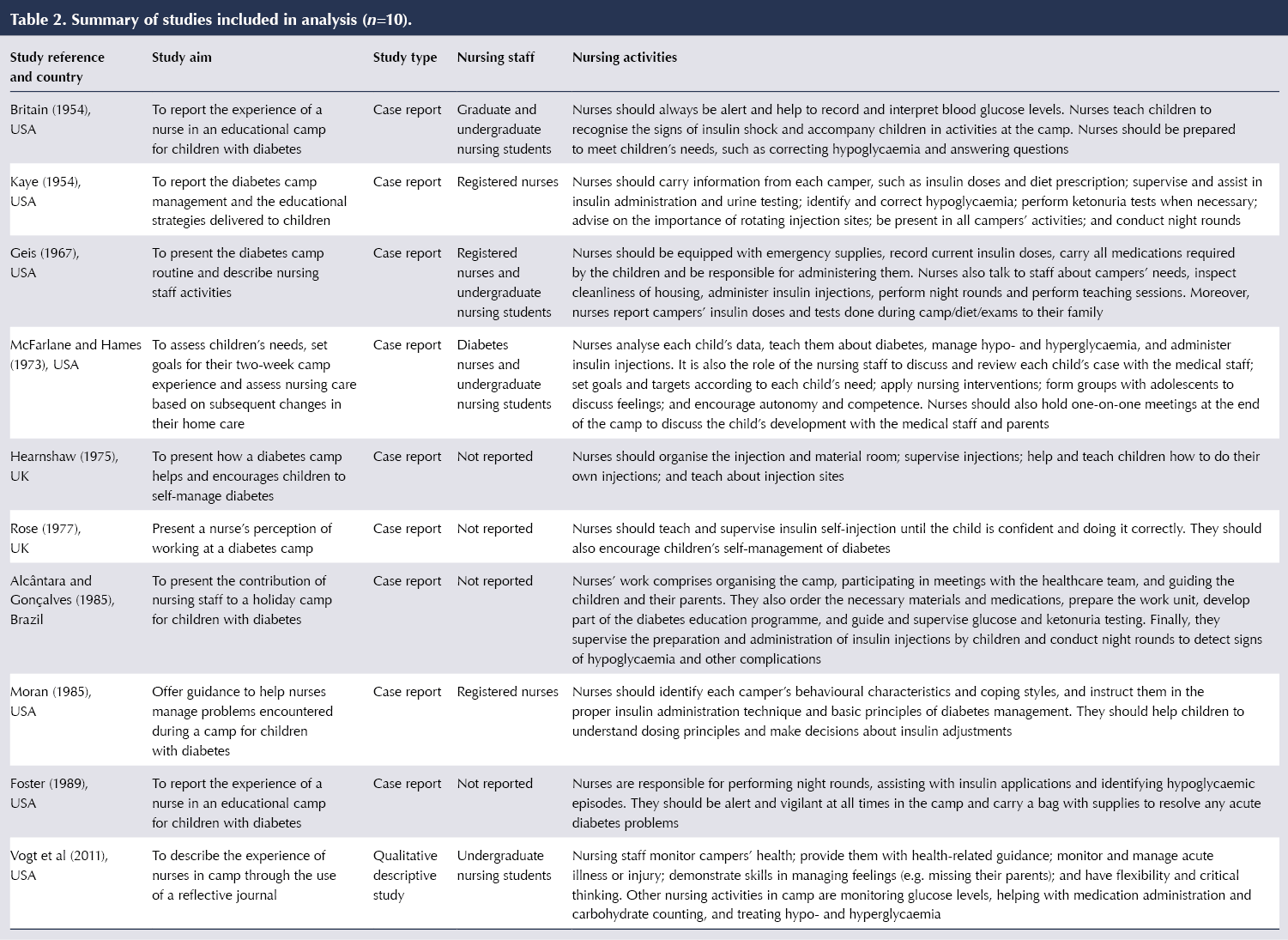

The studies included in the synthesis were published between 1954 and 2011; nine were in English and one was in Portuguese. Nine studies were experience reports and one was a qualitative descriptive study.

Results of analysis

Top-level details of the ten studies are presented in Table 2. The studies highlighted several roles for nursing staff in diabetes camps. The first of these was checking and assessing blood glucose data, as well as recognising and treating hyper- and hypoglycaemic episodes. Performing night rounds provides better supervision of glycaemic variation, which often has no signs and symptoms (Kaye, 1954; Geis, 1967; Alcântara and Gonçalves, 1985). The rounds are necessary for understanding glycaemic variations and preventing acute complications.

Nursing professionals were observed in all studies as key to the education process for self-management of diabetes. The supervision of and education on insulin therapy enhances individuals’ quality of life as well as reducing the occurrence of inadequate insulin absorption and lipohypertrophy (Spray, 2009).

The role of nurses in promoting self-care and autonomy was observed in seven studies. By being encouraged in this, young people with type 1 diabetes change their attitudes and become active agents of their own diabetes management (Kaye, 1954; McFarlane and Hames, 1973; Hearnshaw, 1975; Rose, 1977; Alcântara and Gonçalves, 1985; Moran, 1985; Vogt et al, 2011). Greater adherence to the diabetes therapeutic regimen can provide young people with healthy lifestyle habits and optimise metabolic control (American Diabetes Association, 2019).

Although dietitians play a part in many camp educational teams, this review also highlighted nurses’ roles in assisting carbohydrate counting (Vogt et al, 2011). It is especially relevant that nurses pursue additional education in the nutritional management of diabetes (Ojeda, 2016). Improving healthy-eating habits prevents hypo- and hyperglycaemic episodes, facilitates insulin dose adjustment and enhances safety during physical activity. Furthermore, by teaching carbohydrate counting management, nurses can help young people with diabetes to have a more diversified diet, dispelling the belief that people with diabetes cannot consume some foods, which can also improve their social life.

With regard to family involvement in diabetes care, the development of reports and post-camp meetings with family members reinforces the importance of sharing the learning benefits achieved at camp with all family members (McFarlane and Hames, 1973; Venancio et al, 2017). Nurses’ role in family-centred communication was also described in one study, highlighting that some of the difficulties experienced by campers may be part of family issues with diabetes management as well. Nursing reports can contribute to family members feeling safe and confident in the care of the children when they return home.

It is essential to acknowledge the difficulties encountered by each person with type 1 diabetes before planning and executing educational programmes aimed at strengthening self-care practices. The managerial role observed in this study suggests that nurses are ideal to lead education initiatives in diabetes camps. Nursing staff were recognised as being responsible for managing the camp’s healthcare supplies and organising the emergency team (Alcântara and Gonçalves, 1985; Foster, 1989). Given that nursing professionals are trained to manage physical, human and information resources to achieve the best healthcare assistance (Molayaghobi et al, 2019), our findings reinforce the potential of nurses in coordinating the camp activities, providing better care to young people with diabetes.

Conclusions

The role of nursing staff at diabetes activity camps covers healthcare, psychosocial support and camp management. Studies on the role of nurses in diabetes camps provide recognition of these professionals’ work and improve practice. Future studies are necessary to understand the required training standards for nursing staff in order to assess nursing performance and quality indicators. Moreover, future work in the field of diabetes nursing in camps should document the attributions of these professionals and broaden the current understanding of their roles, reinforcing the relevance of nursing professionals in diabetes camps and nursing education.

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025