The National Paediatric Diabetes Audit (NPDA) established that the number of young people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes tripled over the previous 10 years and is likely to continue to rise (Royal College of Paediatric and Child Health [RCPCH], 2021). It is a more aggressive phenotype with greater lifetime risk than adult-onset type 2 diabetes (Misra et al, 2022).

Statistics show that 75% of families who have a young person diagnosed with type 2 diabetes have experience of caring for someone with the condition, compared to just 5% of families with a young person diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (Shah et al, 2022). Increased risk of youth-onset type 2 diabetes may not always be appreciated by families who have experience with adult-onset type 2 diabetes, and a lack of insulin dependency in those diagnosed without ketosis and an HbA1c <69 mmol/mol may generate false complacency (Shah et al, 2022). Creating a pathway with clear treatment aims is important for achieving diabetes control and instilling the importance of managing this lifelong condition.

Background and prevalence

The Bradford Children’s Diabetes Team (CDT) in West Yorkshire has seen an increased and sustained demand over the last five years. Since 2017, the total caseload for all types of diabetes has increased by 36 patients, and the number of patients newly diagnosed with all types of diabetes has increased from 25 in 2019 to 50 in 2021 (RCPCH, 2023a). The rapid rise it has witnessed in the number of children and young people being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes represents 12.1% of its caseload, compared to an average of 3.4% in England and Wales.

The Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) Study Group (2013) observed that, despite intensive intervention, cardiovascular disease prevalence is likely to be increased in the third and fourth decades of life for youth with type 2 diabetes. In the adult population living with type 2 diabetes, immediate intensive treatment is necessary to avoid long-term complications and mortality, and those with an HbA1c >48 mmol/mol during the first-year post diagnosis have worse outcomes (Laiteerapong et al, 2018). Longer-term outcomes for this vulnerable youth population are lacking and further studies are required (Linder et al, 2013).

Young people with type 2 diabetes are less likely than older adults to receive all of their recommended annual care processes. In 2019–20, 27.8% of those <18 years received them all, compared to 51.6% of those aged 60–79 years (NHS Digital, 2021). They are also less likely to have an HbA1c <58 mmol/mol.

Youth from ethnic minority groups and who are living in deprivation, often with high rates of obesity, are disproportionately impacted by type 2 diabetes (Nadeau et al, 2016; Misra et al, 2022; NHS Digital, 2022). The local centre has an ethnically diverse population and a very high proportion of children and young people with diabetes living within the highest quintile of deprivation (67.1% compared to 23.7% in England and Wales). Within the region, 50.4% of the unit’s cohort are of South Asian heritage compared to the average of 7.9% nationally.

NICE recommends that from diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, young people and their families should be offered tailored education on core topics, such as diet, exercise and complications. Issues such as social considerations and culture should also be taken into account (NICE, 2023). Type 2 diabetes occurs in complex psychosocial and cultural environments, and making sustained change and adhering to medical recommendations can be a struggle (Nadeau et al, 2016). Food insecurity, where limited budgets lead to a diet high in cheap, energy-dense foods and low-quality carbohydrates, also increases the risks and challenges of diabetes management for young people, where nutrition plays a vital role in management (Annan et al, 2022).

Current first year of care

In late 2021, the CDT conducted an audit on the 19 young people who were in the service at that time and had completed a year of care. This concluded that those who had the greatest reduction in weight and HbA1c over the year had started on insulin and metformin at time of diagnosis, had frequent contact in the form of both face-to-face visits and telephone contact, and had received support at school. Those who gained the most weight and had the greatest increase in HbA1c had complex needs, more challenging family situations, missed medication doses and regularly did not attend appointments. The NPDA has stated that type 2 diabetes clinics that are offered for young people are much more poorly attended than those for young people with type 1 diabetes (RCPCH, 2021). Whilst Lee (2020) noted that young people find clinics an opportunity to gain medical advice and a temporary boost in motivation, hospital appointments can also be anxiety-provoking and an unwelcome reminder of their condition. Lee advocated that the focus needed to shift from patient-only diabetes clinics to better suit the group needs.

In 2022, the CDT welcomed the opportunity to work alongside community partners and offer a short programme of weekly jiu-jitsu and allotment sessions that also educated on healthy eating and family behaviour change. Although the team hoped that this partnership would cater for the suggestions set out in Lee’s findings, the uptake was poor. Of the 19 young people offered the sessions, six started out and only two completed the full 12 weeks. The impact that the Covid-19 pandemic had on this partnership made it challenging to evaluate any measurable outcomes.

First year of care pathway development

The CDT had already introduced a robust pathway for the management of type 1 diabetes based on the pathways produced by the Sheffield and Leeds CDTs. The increase in diagnoses of young people with type 1 diabetes, and the social complexity of the cohort, adds to staff pressures to deliver timely education. Subsequently, this impacts on the care of young people with type 2 diabetes, particularly those not on insulin therapies. This cohort is frequently viewed as those who can wait for review, as they are not seen to be an immediate concern from sub-optimal glucose control. However, the TODAY study established that type 2 diabetes has a more aggressive course in youth despite good medication compliance, and recommended early intervention to achieve glycaemic control and minimise the risk of complications (Linder et al, 2013).

The team reflected during twice-monthly quality improvement meetings that, whilst it was clear that the need for whole family education and intensive support were required (Pike et al, 2019), this was often not what was delivered to type 2 diabetes families. The audit demonstrated that the frequency and type of contact that families had was variable. Family-based interventions that include healthy nutrition have been shown to result in a moderate reduction in BMI, when delivered by a specialised multidisciplinary team (Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee et al, 2018).

With the publication of new guidelines (Soni et al, 2021), the team set out to map the ideal first year of care. A paediatric diabetes specialist consultant, nurse and dietitian were identified to lead on the process. The developing pathway was regularly shared with the wider team, and amended based on team feedback and clinical experience. Once the proposed pathway was established, a 12-month trial was agreed, with a view to auditing HbA1c, weight, blood pressure, lipid profiles and quality of life at one year, compared to the previous cohort (Appendix A).

The pathway has clear time points for when HbA1c, blood pressure and lipids should be monitored. It also advises clearly when medication should be increased or reduced, based on the recommendations of Shah et al (2022) and Soni et al (2021), evidence from Linder et al (2013) and the TODAY study on the importance of intensifying pharmacological therapy in conjunction with education to reduce the risk of long-term complications and mortality.

Challenges of the proposed service delivery

The working version of the first year of care pathway began in September 2022, with the view that the team would trial it with the people diagnosed after this date. Since then, eight patients have been diagnosed with what appeared to be type 2 diabetes. Of these, two were treated for type 1 diabetes, owing to ketosis or uncertainty with diagnosis; two were treated for suspected type 2 diabetes, but have had positive autoantibodies; two attended the children’s ward but, owing to bed capacity, were discharged and followed the pathway as outpatients; one was diagnosed in a general paediatric clinic and was followed-up on an outpatient basis; and one was admitted and followed the pathway as directed. The barriers encountered during this initial introduction reflect the complex nature of integrating a new standard process.

The two patients with positive autoantibodies both presented with a strong family history of type 2 diabetes, overweight, South Asian ethnicity, presence of acanthosis nigricans, long history of polyuria and polydipsia, and were not ketotic. The first patient had an initial HbA1c of >69 mmol/mol, but met target glucose levels within two weeks of commencing full-dose metformin and did not start basal insulin therapy. The second patient was commenced on basal insulin therapy at diagnosis with an HbA1c >130 mmol/mol, and was quickly moved onto bolus insulin with all meals because of the difficulty gaining adequate glucose control in a timely manner. Whilst both were presumed to have a likely diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, when the antibodies were reviewed at the first clinic appointment four weeks later, they were both strongly suggestive of type 1 diabetes.

Accurate diagnosis is likely to be an ongoing challenge, as the latest NPDA report showed that 42.3% of young people with type 1 diabetes were overweight or obese, in addition to 92.8% of those with type 2 diabetes (RCPCH, 2023b).

The cornerstone of the type 2 diabetes pathway is intensive education with a dietary focus and an attempt to reduce long-term micro- and macrovascular risk. The future may bring a hybrid approach to ensure that young people, regardless of their diagnosis, are coached and encouraged to achieve a healthy weight and meet targets for all other risk factors in order to provide a legacy for a healthier future.

Aside from these complexities, the nature of a cohort that requires intensive management must be considered. Within the Trust, the reliance on interpreting services is significant. The frequency of appointments set out in the proposed pathway calls for a significant number of clinical hours, which will impact on the interpreting services the Trust can provide. An alternative solution, given the high proportion of families of South Asian origin, could be to consider a business case for an in-house, multilingual family support worker.

Within the team, the clinical hours required to provide this level of care will be significant – for units that do not have a whole-time equivalent dietitian, the pressure to deliver the diet and exercise sessions within the time frame may be unrealistic. NICE (2023) recommends that information should be tailored in timing, content and delivery to meet the needs of families. Although the proposed pathway outlines the topics required for education, the number of sessions required to deliver this information will vary, and is likely to be more for families with additional needs, learning disabilities or where English is not the first language. It is likely that the allocated key worker will need to be responsible for ensuring that the relevant requests for blood tests and ultrasound scans, and the delivery of education are allocated and conducted at the appropriate times over the first year of care.

NICE also recommends that, at diagnosis, young people with suspected type 2 diabetes are referred to a multidisciplinary paediatric team. Those under 16 years are likely to be seen within specialist diabetes services (89.3% of those under 12 years and 91.6% of those 12–15 years). However, as age increases, the National Diabetes Audit has reported that young people with type 2 diabetes are more likely to be exclusively under the care of their GP (70.1% of 16–18-year-olds were under specialist secondary care; NHS Digital, 2023). Within this Trust, young people over the age of 16 years who have had no previous admission to the paediatric ward are likely to have inpatient stays on adult wards. For young people aged 16–18 years, local policy should be considered to ensure that those diagnosed within this bracket on an adult ward or in primary care are referred to the appropriate team for specialist support.

Conclusion

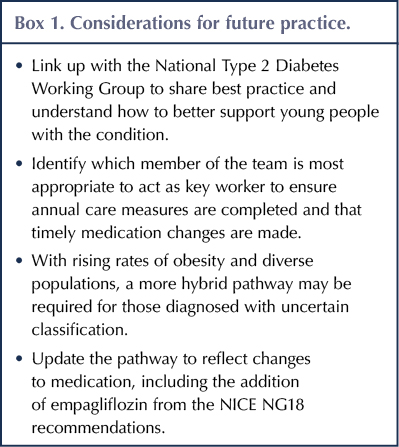

Type 2 diabetes is rapidly rising in the youth population and, as the understanding of how to better manage this condition changes, so does national and international guidance. The pathway will require annual review to ensure changes to guidelines are reflected in the service delivered. The introduction of a new process is not without challenges. Nevertheless, the creation of a standardised first year of care was to ensure that families diagnosed with this complex condition are provided with a clear plan of their treatment pathway. Future work (Box 1) will review which member of the team is most appropriate to act as key worker and ensure annual care measures are completed and medication recommendations are followed in a timely manner.

As the pathway is in its infancy, the audit at 12 months will be key to understanding whether this standardisation has been beneficial. Learning taken from the audit will be shared through the National Type 2 Diabetes Network working groups and will guide any further improvements. As a team, this work will also shape further quality improvement projects for future practice.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge the Birmingham City University’s Children and Young People’s Diabetes Care Module.

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025