Background

Type 2 diabetes is an ever-growing national and international concern but, despite this, the impact of the disease continues to grow (Hicks, 2015; Valabhji, 2018). As well as its physical effects, type 2 diabetes has a substantial emotional impact upon people with the condition and their families (Berry et al, 2019). In addition, type 2 diabetes has substantial socioeconomic implications; its treatment accounts for just under 9% of the annual NHS budget, around £8.8 billion per annum (Diabetes UK, 2018). It is therefore essential that effective support for people with type 2 diabetes is achieved.

Study aim

The aim of the current research was to evaluate how nurses in a primary care setting support the self-management of people living with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

This article conveys the key findings from research that investigated the perspectives of practice nurses who are directly involved in the care of people with type 2 diabetes. The research was conducted within the West Midlands region of the UK. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from Staffordshire University and the NHS Health Research Authority (HRA).

A qualitative research strategy was employed, which included semi-structured interviews. All participants were required to be working as a practice nurse, supporting people with type 2 diabetes, and to have a minimum of one year’s experience in this role. Invitation letters and information sheets were sent via practice managers to potential participants. These communications highlighted that participation was voluntary and that participants could withdraw at any point of the study without needing to offer an explanation.

In the interviews, respondents were invited to discuss their experience of, and perspectives on, the support of people with type 2 diabetes in primary care settings. This enabled in-depth insights into nurses’ perspectives to be obtained. A semi-structured interview method was adopted, which followed a flexible approach with open-ended questions. While a topic guide shaped the interviews, this flexibility ensured interviewees were free to raise matters that were important to them. The topics covered included the experience of participants in supporting people with type 2 diabetes; how participants assisted patients to achieve self-efficacy; available resources to support the practice nurse role; and perspectives on how the practice nurse role can facilitate good care. Participants were interviewed until data saturation was achieved. The interviews had a mean duration of approximately 30 minutes.

A process of thematic analysis was undertaken to analyse the responses. This required reading and re-reading of transcripts, closed-coding of the text and the organisation of these codes into broader themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This process enabled the key content of interviews to be established and addressed commonalities (and divergence) across participants’ accounts. The three principal themes identified were skills and dispositional qualities; accessing resources; and medication and prescribing.

Results and discussion

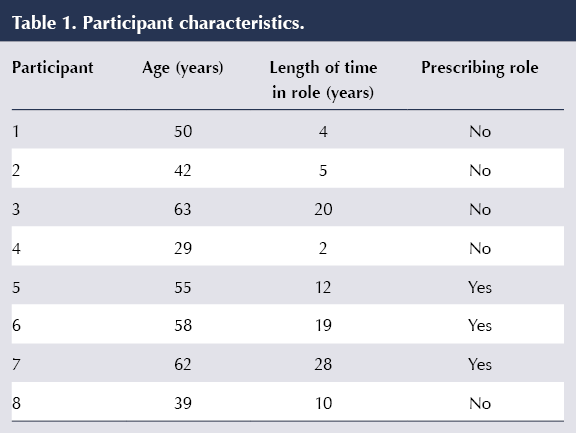

Eight practice nurses participated in the study. Although there was no exclusion criterion on gender, the sample consisted of female nurses only. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

The themes that emerged from the interviews are discussed below.

Theme 1: Skills and dispositional qualities

All participants acknowledged multiple skills and qualities that they felt enhance the self-management and motivation of people living with type 2 diabetes. A commonality across the interviews was recognition of the importance of building a good rapport with patients and the centrality of good communication skills in achieving this rapport. One of the biggest barriers healthcare professionals encounter is meeting and understanding the needs and continued demands of people with type 2 diabetes (Shrivastava et al, 2013). Participant 1 acknowledged the centrality of communication to good practice when discussing how the nurse–patient relationship could be successfully supported:

“…definitely down to communication yeah, you’ve got to be on their level, you’ve not got to be this strict tyrant who’s going to be, you know, preaching at them. I think that just starts with the walls coming up.” Participant 1

Empathy and understanding are also required for ensuring that communication meets person-centred requirements. Delivering individualised advice, tailored to patient need, is considered paramount. This is crucial when the care is of a facilitative nature:

“I try and find what they enjoy and what their motivating triggers and barriers are; there’s no point telling someone to go out running one night a week if they don’t enjoy it because they won’t do it. Or to attend a slimming class if they are skint or lack in confidence, because they just won’t go.” Participant 8

This quote also shows how an understanding of patients’ needs has to be reconciled with realistic goal setting and clear planning (Polonsky et al, 2010). Empathy and understanding are key qualities but these need to be complemented by clear, effective approaches to setting goals and management planning. It is worth noting, however, that this differs from the imposition of external targets, which could be an impediment to person-centred support as, if an excessive emphasis is placed on the importance of targets, it could divert attention from aspects of care that are less amenable to measurement (Harwood et al, 2013).

Communication needs to be purposeful and grounded in the nurse’s self-directed planning and organisation. This is addressed further in the following quote, in which it is highlighted how documentation skills are vital as a way of ensuring that messages could be revised according to patient responses:

“…I always document carefully and I could see I had seen him for the past three years and he had done nothing different at all and I was just saying the same things, so I said to him can I just ask what you get out of coming here because for the last three years I’ve told you the same things and you’ve done nothing about it, and he said to me he did not understand how to change his diet.” Participant 3

Theme 2: Accessing resources

The wider availability of resources provided to enhance patients’ self-management of type 2 diabetes was discussed by all participants. It was highlighted that there was limited access to any healthy lifestyle services (Peter et al, 2011), as previous services had been decommissioned and, consequently, the majority of lifestyle management was now undertaken in-house by the practice nurses:

“We used to have lots of services… most of that stuff has been taken away from us; it’s a difficult one really, it’s like your smoking cessation has been taken away from us. I mean what’s the best thing to tell a diabetic to do: stop smoking, isn’t it really, to stop them getting peripheral arterial disease, but there’s nowhere to send them.” Participant 6

Diabetes is often linked with depression; this might increase pessimistic feelings, and a lack of self-efficacy could potentially demotivate individuals from making the changes required to self-manage their condition (Graffigna et al, 2014; Nash, 2015). Participant 8 considered dealing with these underlying problems to be a priority in the improvement of self-management:

“I think it is important to deal with any underlying issues that can stop patients managing their diabetes. Depression is a biggie; I try and tackle this with patients and get them to engage with the wellbeing services before I knock them further putting more pressure on them. I think the better a patient is in their mind, the easier it is to get them to engage.” Participant 8

Practice nurses are at the forefront of care, yet their limited time with patients can be spent finding access to services and making referrals. These referrals can become subject to a lengthy delay, which may then result in demotivation. Furthermore, the participants felt communication between practice nurses and community-based services impacted on diabetes management due to communication barriers and conflicting information, but they did not offer suggestions on how this situation could be improved.

Additional resources that were discussed were online services and health apps. However, while all the participants mentioned signposting patients to online resources, such as Diabetes UK, none discussed the value of such services, or whether they actively demonstrated this resource to the patients. In addition, limited attention was granted to the use of health apps. One of the possible reasons for this is alluded to below:

“That’s the way we are all being pushed to go, but I’m really struggling getting people to engage… it’s amazing just how many people just don’t want it, not interested. It’s very time-consuming for us as well but I do try, I do try… you’ve got people there with smartphones sitting there in front of you – I haven’t got an answer as to why they are not interested, because if you show them they appear interested but they don’t – I can’t think of one person that use the health app.” Participant 7

This acknowledges that the use of technology in self-management is pertinent but that there can be challenges in engaging people in its use. Impediments to the employment of technology are, therefore, not only structural (e.g. limited external capacity of services) but could also be a consequence of patient disposition, or nurse–patient interactions. As the participant highlighted, this is noteworthy considering the familiarity of smartphone usage for many people. Alternatively, it could be that patients do not view the management of their condition and personal resources such as their phone as compatible. It is possible that a lack of compliance could impact upon nurse motivation (Jansink et al, 2010), leading them to feel less inclined to promote these resources. Further investigation is required to grasp why there could be impediments to embedding technology within self-management.

Theme 3: Medication and prescribing

Medication was a further key theme raised across the interviews. This topic was salient for participants regardless of whether or not they were a qualified prescriber. Of the participants, the majority (five) were not in a prescribing role, and all of these had mixed perceptions on where their roles stood in terms of providing patients with medications. For example, Participant 4 felt able to discuss alterations to medication with a GP, yet this would not involve the GP assessing the patient themselves. The heavy involvement in the titration of medication was also conveyed by Participant 8:

“I do find myself advising them on titration, which I suppose I shouldn’t as I’m not a prescriber, but what are you supposed to do? You can’t just let the patients go on poorly controlled, and what a waste of resource… if you referred everyone and then they have to wait ages.” Participant 8

Partaking in this process is known as prescribing by proxy, meaning nurses are independent in their decision-making regarding care and treatment, but have no actual legal right to prescribe (Bradley et al, 2005).

Although only three interviewees were qualified prescribers, their consistent view was that prescribing made their job role easier and enhanced the quality of care. The following quote demonstrates this perspective, addressing how much the prescribing role assists:

“Massively because I can up and down prescriptions and change things and it lets you do it holistically, and it saves the waiting time and talking to doctors, who perhaps don’t always understand it as much as you do. They are just saying: ‘what do you want to prescribe?’” Participant 7

However, another participant expressed unease with some of the updates available for prescribers on diabetes medication. They felt it was too complex and aimed at GPs, who ultimately do not provide the reviews for patients:

“There are some updates available because we went to one last week with a drug rep. It was a bit over my head, it was a bit too – erm, what’s the word I’m looking for, erm – ‘scientific’.” Participant 5

This could discourage prescribers from making the choice to prescribe for patients with type 2 diabetes, potentially hindering the support of self-management. This is in line with the findings of Drennan et al (2014), who found decreasing numbers of actively prescribing nurses within the UK.

Study limitations

The limitations of the research design must be recognised. As a small-scale qualitative study with a focused sample, no claims to generalisability are made. The study relates to the particular experiences of a group of professionals within one region of the UK.

Conclusions

Facilitating the self-management of type 2 diabetes is a complex challenge, due to the breadth of factors that shape people’s experience. Communication is central to nurses’ endeavours to facilitate effective self-management of the condition. It is vital that communication is predicated on a sound understanding of each patient’s disposition and circumstances, so that person-centred support can be delivered.

The patient–nurse interaction within primary care, in itself, is not sufficient to ensure that high-level support of people with type 2 diabetes is achieved; a wider context of support also needs to be accessible. Increasing resource constraints upon health and social care services could therefore pose a challenge for practice nurses. The inclusion of the prescribing role within the practice nurse remit also shows how professional boundaries are constantly shifting. If role boundaries are unclear and access to external support is constrained, then this could impede nurse–patient interactions where the goal is to facilitate the self-management of people with type 2 diabetes.

It is therefore recommended that greater attention should be granted to ensuring clarity of role boundaries and also the nature of the relationship between diabetes support and other services. This can help to generate a more coherent context within which the self-management of type 2 diabetes can be facilitated. Person-centred communication must also be reconciled with goal setting for patients, ensuring that goals are tangible, realistic and sustainable.

Developments that will impact your practice.

7 May 2025