Notwithstanding the COVID-19 pandemic, transplantation rates are likely to grow, especially as the UK now has a “presumed consent” approach to organ donation (NHS Blood and Transplant, 2020). Furthermore, long-term follow-up of patients undergoing transplantation is increasingly managed in local district hospitals rather than in large transplant centres, and therefore many diabetes nurse specialists or primary care nurses may see patients with diabetes who have undergone organ transplantation. The new guidance from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists and the Renal Association (Chowdhury et al, 2021) on prevention, detection and management of PTDM is, therefore, welcome. The guidance carries the caveat that many studies in the area are small, short-term and uncontrolled, and hence the evidence behind many of the interventions is really quite weak.

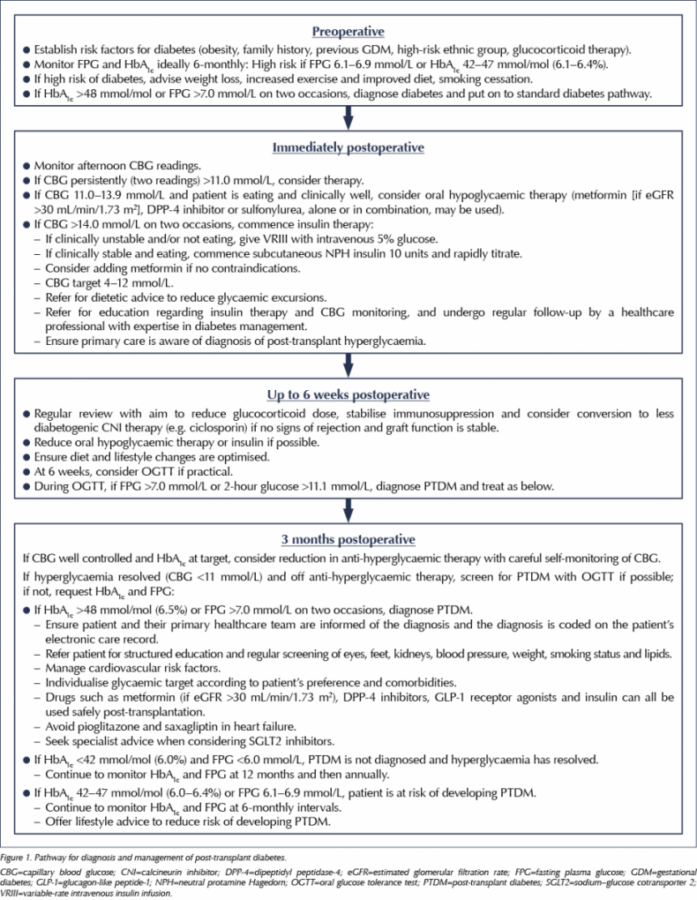

The guidance outlines the epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention strategies for PTDM. However, the main core of the guide is the detection and management of this condition (Figure 1). For centres managing patients undergoing transplantation, the guidance is clear that PTDM should not be diagnosed within 3 months of transplantation. The reason for this is that high doses of steroids and immunosuppression, coupled with stress from the operation, infection, pain and other factors (such as enteral feeding), very frequently lead to transient hyperglycaemia, which may improve with time. Nevertheless, this immediate postoperative hyperglycaemia should be actively screened for and managed.

The optimum screening method for postoperative hyperglycaemia is the use of afternoon capillary blood glucose (CBG) measurements. This is because the use of steroids and immunosuppression (especially calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus) often leads to postprandial hyperglycaemia, and such patients may quite frequently have normal fasting glucose levels. The guidelines suggest that if hyperglycaemia is significant and persistent (two CBG measurements >11 mmol/L), treatment should be initiated. If CBG values are 11.0–13.9 mmol/L, oral hypoglycaemic therapy with metformin (if renal function allows) or a sulfonylurea may be tried. If glucose readings are above 14 mmol/L on two occasions, however, insulin therapy is advocated, either intravenously using variable-rate insulin infusion (if oral intake is poor), or with once-daily NPH insulin given subcutaneously in the morning as a starting regimen. Patients will need input from the multidisciplinary diabetes team, including diabetes nurses and dietitians, to help improve lifestyle and learn insulin administration and glucose testing.

Most transplant patients are seen weekly following discharge, and glucose levels should be regularly reviewed. As immunosuppression doses are reduced, hyperglycaemia may improve and clinicians will need to proactively reduce therapy to avoid hypoglycaemia.

At 3 months postoperatively, most patients are on stable immunosuppression doses and, therefore, can be screened for PTDM using either an oral glucose tolerance test or, much more conveniently, with an HbA1c test, using the standard criteria for diagnosis of diabetes advocated by the World Health Organization (fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L, 2-hour glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L or HbA1c ≥48 mmol/mol [6.5%]). If diabetes is confirmed, the transplant team should ensure the diagnosis is added to the patient’s clinical record and their primary healthcare team is informed, so that structured diabetes education and regular screening and care can be provided.

If glucose management is difficult in a person who develops PTDM, consideration can be given to changing immunosuppression regimens to less diabetogenic ones, which may reduce hyperglycaemia, although this must be tempered with the increased risk of rejection. For example, tacrolimus appears to be much more diabetogenic than ciclosporin, although risk of rejection with the former is significantly lower (Sharif et al, 2011).

The guidance also outlines the importance of screening for diabetes in patients awaiting transplantation. This can be difficult using HbA1c because anaemia (commonly seen in patients on dialysis) can falsely lower HbA1c, so at least yearly fasting plasma glucose checks should be performed in patients awaiting transplantation. Finally, prevention of diabetes is discussed for this group. Improvements in diet and physical activity may have a role in reducing the risk of developing PTDM.

Overall, this guideline has reviewed all available evidence and developed a coherent pathway in this important condition, which transplant and diabetes teams may find useful to follow. As the area is currently rather evidence-poor, the guideline also highlights areas required for further research and some possible audit standards, in the hope that areas lacking in evidence could start to be developed, and detection and management in this group of patients improves over time.

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025