I was 14 years old when I developed diabetes. It was February 1955, and I spent 12 weeks in hospital being stabilised. Today, such a long spell in hospital would be seen for what it was: a waste of time and money, for patients cannot be effectively stabilised until they return home to their normal activities. Although there was plenty of time for both patients and parents to be given formal education on the management of diabetes, none was offered. I did weigh my cereal and bread each morning, but mastering other exchanges was not necessary as alternatives were not an option, and I only made one attempt at injecting myself before I was discharged from hospital.

My mother’s introduction to the management of diabetes was just ten minutes with the consultant, on the morning I went home. “Your daughter should not do anything too active”, she was told, “and I fear she is unlikely to undertake full-time employment”. Not a very cheery prospect for someone whose sole ambition at that time was to make the under-16s netball team. Such was the advice given 64 years ago: acceptable at the time, but hardly credible today!

To put this guidance into perspective, let me remind you of what life was like in 1955, when Winston Churchill, the great wartime leader, was Prime Minister. The star of children’s television was Muffin the Mule, and the teenager’s heart-throb was the rebellious 24-year-old film star, James Dean, who tragically died in a car crash just three days before the release of the second of his three films, Rebel Without a Cause. Top of the Pops was a programme on the wireless, transmitted from Radio Luxembourg, and the musical hit of the day was Oh My Papa, played by Eddie Calvert on his Golden Trumpet. Television sets were a luxury and many homes did not possess one, until 22nd September, when the launch of ITV brought a big rise in sales! Of the few personalities known to have diabetes, none were very famous. There was Hamilton (Ham) Richardson, an American who reached the quarter finals at Wimbledon, and an elderly actor, Leo Franklyn, the father of the dashing William Franklyn, who for many years appeared in the Schweppes advert “Schhh… You know who”!

Our currency was expressed in pounds, shillings and pence, and for fourteen shillings and elevenpence, just 75p, you could purchase a very fashionable ladies’ blouse. Blakes Motor Company would allow you to hire a car for the day for 25 shillings, a mere £1.25p, and for £14 you could have a honeymoon in The Lake District! The Echo, which cost tuppence, less than 1p, featured “The Back Entry Diddlers”, “Curly Wee and Gussie Goose” and “The Finishing Touch”. The latter was a lottery in which readers gambled on the first and last letter of a short anecdote. It is said that a sister at Newsham General Hospital once walked into a ward one evening and announced loudly, “Who’s got VD?” A red-faced man in the corner slowly raised his hand. “You’ve won The Finishing Touch!”, she said.

The diagnosis

In the winter of 1954/55 there was a flu epidemic, which I succumbed to in mid December. By early January I was well again but, despite a good appetite, I began to lose weight. I also developed an unquenchable thirst, for which I consumed copious volumes of fluid at frequent intervals. My life was dominated by the constant desire to drink. As I travelled home on the bus from school, my mind would concentrate on two things: the location of our kitchen tap and the route I would take to it. If the bus stopped at the traffic lights – and it inevitably did – my torment would be aggravated by the sight, from my seat on the top deck, of the huge poster advertising Cadbury’s Dairy Milk Chocolate, which showed milk pouring from two glasses into a chocolate bar. In mid February, as I gave up the struggle to attend school, my diet became predominantly more liquid than solid. In place of each meal, I would request either tomatoes and sugar, grated apple with sugar and milk, or Lucozade. Such foods, I would later discover, were the preference of many young people with diabetes just prior to diagnosis.

On the evening of Thursday 17th February 1955, I was admitted to Alder Hey Children’s Hospital under the care of Dr Anne McCandless, who within a few hours had diagnosed my condition as diabetes. I was just one of five patients diagnosed that year. My appearance was classic for someone newly diagnosed: short in stature, I was 1½ stone (10 kg) underweight. On admission to hospital I was very dehydrated and, though barely conscious, I do remember the admitting casualty officer estimating my age to be 10 – I was 14 and most insulted! My blood glucose level was 950 mg%, or 52.7 mmol/L in the units of today, ten times greater than normal (Image 1). My serum chloride and bicarbonate were at equally dangerous levels. The casualty officer wrote in my notes “A thin, slightly dehydrated child, conscious but apathetic”.

In those days, the criterion for the treatment of ketoacidosis was hourly urine tests, a somewhat precarious yardstick to use, as the amount of glucose in the urine is only an indirect guide to the amount in the blood. The test produced a colour reaction ranging from blue through green, yellow and orange, to brick red. For the first 24 hours the colour reaction to my urine test remained brick red and, as a result, I was given 20 units of insulin hourly. Then, as the colour changed, indicating that the glucose content of my urine had fallen, I was given 20 units of insulin if the colour was orange and 10 units if it was yellow. Surprisingly, despite the use of such vague data, very few patients succumbed to diabetic coma. Blood glucose analysis was undertaken, but it had its limitations as it involved a laboratory procedure that took four hours to complete.

Thirty-six hours after my admission to hospital, the drips were taken down and I was transferred from an isolation cubicle to an ordinary ward. On the way there, the nurse escorting me encountered one of her colleagues. On hearing where we were heading, she said excitedly that a diabetic was to be admitted to the ward that day. Though I hadn’t a clue of what or to whom the nurse was referring, I do remember thinking, “now that could be interesting!”. I was right; a child with diabetes in those days was an interesting occurrence, and many medical and nursing staff came to look at me!

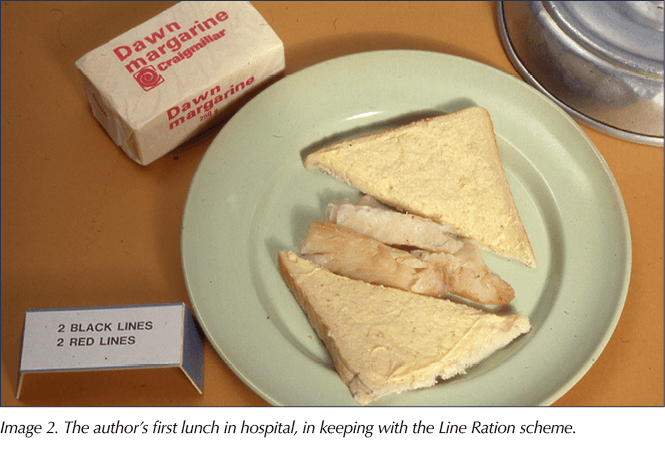

As soon as I arrived on the ward, Dr McCandless came to see me with the good news that I could have some lunch. Having not eaten for two days, I was ravenous, and I began speculating on what the meal might be. Chips, sausages, baked beans, roast potatoes? The food arrived under a tin cover and, as it was removed, I groaned in disbelief. There before me was a small piece of steamed fish with one slice of white “hospital” bread and margarine! Labelled 2 Black and 2 Red Lines (Image 2), it was scarcely appetising, yet I ate it readily, proving that if you are hungry enough you will eat anything!

The appearance of the teaching staff on the Monday morning came as a shock to me, for I had assumed that this unwelcome spell in hospital would at least exempt me from attending school! I certainly did not share the teacher’s enthusiasm for writing a daily diary – it was a reminiscence of junior school – nor did I relish completing sums for her to assess my standard of education. The sums were simple addition, multiplication and division and, as I was in the second year of senior school, I was outraged and once again insulted! However, my outrage soon turned to panic as I found I was unable to solve the most simple sum! It was an unnerving experience for me, which in hindsight I realise should not have been allowed to take place, for at that stage I was not fit enough to attend lessons.

Life in hospital

Three people controlled the administration of the hospital at the time. Dr Crosby, the Medical Superintendent; Mr Harold Mason, the Hospital Secretary; and Miss Inga Cawood, the Matron. Dr Crosby, who always wore a winged collar, held the key position of authority; even the menu was compiled to meet his requirements. His contribution to the children’s nutritional intake was to insist that we were given either rice pudding or custard each day, and tomatoes had to be served with the supper at least three times a week. Dr Crosby and his wife lived in a spacious flat in the centre of the hospital. For this accommodation they paid a nominal rent of £8 per month, which entitled them to a maid; food supplies, which were replenished daily; and a choice of menu from the kitchen, which at lunchtime always included, for just the two of them, a whole, freshly cooked joint of meat. Fortunately, the catering officer, who had to find the resources to meet these demands, had over 80 staff, including his own butcher. His kitchen was dominated by a coke oven so large that it was later converted into the diet bay! Meals for patients were delivered to the wards in insulated boxes that had been heated in a large hotplate. Heated trolleys were not purchased until 1961, and then they only took out the lunches; they were not used in the evening because the hospital administration refused to pay the porters the overtime rate, which came into force after five o’clock. Despite numerous protestations, this detrimental practice was still in force in 1992.

Matron Cawood was a model of efficiency, and standards under her regime were notably high. A revered disciplinarian, she rigorously enforced the regulations of the establishment, and woe betide anyone who infringed the rules. Unlike today, when visitors may come and go more or less as they please, visiting was permitted for one hour only, on Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday afternoons. The exception was Miss McCandless’s wards, where an additional 30 minutes’ visiting was allowed each evening. Matron Cawood clearly considered this policy to be an infringement of hospital rules and, as the evening visitors waited to enter the ward, she would inevitably arrive to do her ward inspection, which could take at least ten minutes if she so wished. Beds had to be aligned, the correct distance apart and the correct distance from the wall, and sheets had to be turned down the regulation number of inches. All books and toys, including unfinished jigsaws, had to be out of sight, and patients, myself included, had to sit up in bed, hands resting in front of them on the counterpane! A silence fell as, imitating the Colonel-in-Chief of a large regiment, she slowly and deliberately strode down one side of the ward and back up the other, with the anxious sister in attendance. A ceremony of military precision no longer witnessed today!

Wards were strictly for one sex only, boys on one side of the corridor, all in blue hospital pyjamas, and girls on the other, all in white hospital nightdresses. Apart from official visits to other departments, patients were not allowed to leave the ward, and only with special permission could you wear your own day clothes. Receiving gifts of food was not permitted, and if visitors brought in sweets they were confiscated by nursing staff, who at visiting time stood guard at the ward door. Placed in a communal dish, they were shared out once a day, the child in the first bed always getting the prime choice.

The education of patients with diabetes was minimal, and it was rarely offered before discharge from hospital was imminent. I was given no reason for my admission to hospital, nor did I get any explanation for the treatment I was receiving. Getting weary of injections, I asked the two nurses making my bed one morning how long this form of treatment would continue. You could have heard a pin drop. “We are not allowed to tell you,” one reluctantly volunteered, giving knowing looks towards the sister’s desk. “Please tell me,” I begged, “I promise not to tell anyone”.

“Promise,” they both insisted, “cross your heart.” I duly crossed my heart. “You will have to have injections for ever,” one whispered. “You’re lying,” I shouted in horror, “you must be!” In time I realised they were telling the truth, but at that moment I could not check it out for fear of breaking my word and getting them into trouble.

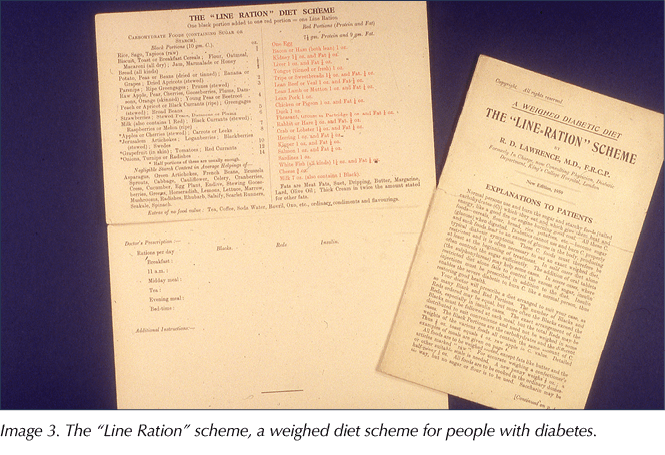

Dietary intake was controlled by the “Line Ration” scheme (Image 3), a regimen compiled in 1925 by Dr Robin Lawrence, who himself had diabetes. Usually referred to as the “Lawrence Line Diet”, the carbohydrate foods were printed in black (Black Lines), and the protein foods in red (Red Lines). Each black portion or line contained 10 g of carbohydrate and each red portion or line contained 7½ g of protein and 9 g of fat. If a red line was deficient in fat then an appropriate amount of butter had to be added to it. So a slice of beef could be served with a knob of butter on top! All foods had to be weighed, but carbohydrates had to be weighed accurately, no matter how small the intake. Portions had to be shaved to measure with a very sharp knife. Such exactness was a nightmare for a mother making sandwiches! I remember my father painstakingly creating a recipe for fruit salad, working through numerous permutations of fruit to find a combination that was not only varied but also measurable to a total of exactly 10 g of carbohydrate. The final recipe was a mathematical masterpiece!

The diets were prepared in the main kitchen and sent to the wards with the other patients’ meals. Patients with diabetes, however, ate their evening meals one hour after everyone else. For whose benefit this was I never discovered! All it guaranteed for us was a dried-up meal stuck to a red-hot plate, a result of flash-heated food left to go cold on the ward kitchen table. There was no flexibility and no allowances were made for dislikes. For example, bedtime drinks were always hot milk with Horlicks or Ovaltine, a tough ruling for those, like myself, who had a strong dislike of all three ingredients! To ensure I understood the importance of eating all my carbohydrate foods, I was instructed to eat everything or I would die! Surprisingly, this austere threat did not unduly upset me, as I attended a convent school and was programmed to follow similar emphatic and often ridiculous instructions without question. In the main I did eat everything, except for tinned peas, which were always shrivelled and hard. I used to hide them in my locker until the late evening, when the night nurse dimmed the lights with red covers and went to the kitchen to make herself a cup of tea. Then another patient and I would use them as missiles, aiming for targets in the beds opposite. Marks were awarded according to the volume of the patients’ cry of “Nurse”!

Life seemed to be dominated by urine tests. First there was the practice of double-voiding. To avoid testing urine that had been in the bladder for some time, it was obligatory to empty your bladder about half an hour before the allotted test time. I found this practice most obnoxious, not because it involved urine but because it forced you to pee on demand and took away the freedom to do so when you desired. Patients who were not able to pass urine at the designated test time were given “the water treatment” – in the belief that the sound of running water makes you “want to go”, every tap within hearing distance was turned on full! If this did not have the desired effect, they would catheterise you; they took no prisoners in those days!

Testing urine was a tedious procedure; you had to collect the urine, then, using an eye dropper, place eight drops in a test tube with a teaspoonful of Benedict’s solution. Then you boiled it vigorously over a Bunsen burner for two minutes. The only advantage offered by this lengthy routine was the break from school. The tests, despite the significance of the results and the presence of gas and a naked flame, were rarely supervised. This simple task could take ten minutes to perform, twenty if the whole procedure had to be repeated because the test tube was knocked over. Sometimes I knocked the test tube over twice! As the urine boiled, the colour changed depending on the amount of sugar present, from blue through turbid yellow and orange to brick red. A blue or negative urine test showed the urine was “sugar-free”; however, this merely indicated that the blood glucose was not above 10 mmol/L, for glucose does not leak into the urine until it has reached this concentration. It certainly did not identify the condition of hypoglycaemia, yet if I reported the result of my test to be blue on two consecutive occasions, the nurses would give me sugar in water. It was always offered in a green Bakelite cup, heavily stained with tannin. My loathing for the taste of this revolting cocktail in a disgusting receptacle remains with me today. One of my first objectives when appointed to the post of dietitian at Alder Hey was to introduce the use of Lucozade!

At home, in place of a Bunsen burner, I used a spirit lamp or a pan of boiling water. If a pan of water was used, the urine had to boil for five minutes. Using a spirit lamp to boil urine in a test tube would provoke my mother to admonish, “Mind what you’re doing!”, for if you did not mind, the vigorously boiling urine would shoot with a crack from the slanting test tube, all down the wall! Monitoring treatment by such a method was distasteful but it was even more repugnant when you were away from home, as you had to take with you all your equipment, including a chamber pot! “Don’t forget your bag!”, my Mother would call after me as I went out the door. I lived in fear of being asked to reveal what was in the loathsome bag, or the zip breaking and the contents spilling out in front of a large crowd of people! Clinistix and Acetest tablets were not in regular use at that time, and yet to be made available were the plastic strips for detecting glucose and ketones in a stream of urine.

Unlike the razor-sharp, micro needles used today, we used thick needles with a heavy glass and metal syringe (Image 4). The needles, far from being disposable, were expected to last for weeks; I think my record was six months! The syringe, which at home I kept in industrial spirit in a metal container, had to be boiled regularly because, as the spirit evaporated, it left a sticky deposit, which in time gummed up the syringe. I rarely boiled my syringe because the process was time-consuming and frequently caused the syringe to crack. Though the use of industrial spirit was an improvement on the laborious task of having to boil your syringe before and after each injection, it did have an expensive disadvantage: the smallest drop of spirit would take the surface off any furniture, leaving a tell-tale mark which clearly identified the culprit! On the ward, needles were recycled. After each injection they were tossed into a large steriliser, where they would bounce around in the boiling water, blunting their points on the metal sides of the steamer. To encourage patients to do as they were told, the nurses would promise them the use of a new needle for their next injection! At home, patients were advised to sharpen their needles on a fine razor stone, or they could be sent away to be sharpened by experts at a cost of three shillings (30p) per dozen!

There were few diabetologists in the 1950s, and most patients were treated by a general paediatrician or physician, usually the one working on the day of their admission. Such widespread care meant many consultants lacked experience and confidence, and as a result they imposed on their patients an exact regime. My experience at Alder Hey was typical of the rigid management of the time. During my final weeks as an inpatient, the consultant felt I would benefit from a couple of hours spent at home. Once in the house, my Mother naturally made some tea, and then came the dilemma: should I or should I not have a cup, as we knew milk contained carbohydrate? After some lengthy discussion we decided I should, as if I did not have a cup of tea my family couldn’t either, and then what else would we do? But then came a bigger problem: how to measure the milk? Eventually we decided I would use a tablespoon, then on my return to the ward the same amount could be deducted from my next portion of milk. We felt very pleased with the way we had handled the situation until the ward sister, instead of congratulating my mother and me for using our common sense, sternly rebuked both of us for eating an unknown quantity of carbohydrate at an unspecified time! Meal times, then, were of prime importance: on the dot, twenty minutes after insulin. On the ward I would sit with knife and fork at the ready, waiting for the clock to reach the allotted time!

Life at home

During the war, those who suffered from diabetes were allocated extra rations of meat, bacon, cheese and eggs, and so it became standard practice for patients with diabetes in hospital to be given their extra protein with a salad in the middle of the afternoon. This custom continued for at least another fifty years, if not longer! As I had been instructed to follow strictly the diet I had been given in hospital, I continued to take this afternoon snack of salad plus protein after I went home. As soon as I got in from school, I would have my teatime carbohydrate: one slice of toast with two poached eggs, and a plate of salad (Image 5). I became an expert at eking out half a slice of toast with each egg. As I returned to a more normal weight, my appetite subsided and this mini-meal became time-consuming and tedious. After twelve months, the mere sight of a salad or poached egg nauseated me, and I finally rebelled and began taking my teatime carbohydrate in a more convenient, attractive form: chocolate biscuits!

Whatever the circumstances, the prescribed dose of insulin and the allowance of carbohydrate could only be altered by the doctor. Until the late 1970s, medical advice was obligatory and accepted without question, and so it is not surprising that I was still following these principles of diabetes management in 1960, when as part of my training I worked as a cook. The job was physically demanding and as a result my blood sugar was always low. Yet I conscientiously continued to take the prescribed dose of insulin, correcting the hypoglycaemia by eating pounds and pounds of biscuits! In one year I gained a stone in weight, eating my way through the profits of The Royal Insurance!

I faced my first diabetic mishap riding a bicycle a few weeks after I left hospital. Knowing I had been forbidden to do anything too active, I went to ask the GP if he felt a bicycle ride fell into this category. The GP, as perplexed as I was over why I had to follow this guidance, thought a ride to a bridge in Tarbock, a mere four miles away, an acceptable pursuit. So one afternoon, unaware of the dangers of hypoglycaemia and unequipped to deal with such an eventuality, I set off with a friend to the bridge. Within half an hour we had reached our destination and, after a sit in the sun, we became bored and decided that, as the ride so far had been uneventful, there would be no harm in moving on. A few yards down the road we saw an enticing sign, “To The Transporter”. The Transporter was a somewhat Heath-Robinson-esque contraption which offered motorists a memorable experience, as it carried them across the river Mersey between Widnes and Runcorn (Image 6). The “car”, as the moving platform was called, was noisy and open to the elements. Suspended by steel cables from a pulley, it cleared the river, by a mere twelve feet at high tide. At low tide you could see the rocks on the river bed below. The actual crossing took about ten minutes but, because of the loading and unloading, the wait between “cars” could be at least half an hour.

My friend and I, tempted by the sign, rode on to Widnes, took the car across to Runcorn and cycled up Runcorn Hill. By the time we got back to Childwall Fiveways, we had ridden some 22 miles and I was sweating, argumentative and wobbling all over the road. My friend’s solution to the problem was simple: “You ride on the inside so that I can protect you from the traffic!” Queens Drive, though not then a dual carriageway, was still one of Liverpool’s major roads! Having struggled the last half mile home, we were then afraid to go in and meet my mother, as we knew we had gone further than we should have! My friend pushed me to the door step, rang the bell and ran away. My mother, seeing my condition, sat me in an armchair and rang the consultant at home for advice. Fortunately for me, she was in. After this rather frightening experience of hypoglycaemia, I was at last instructed to carry sugar with me at all times (Image 7). Carrying small sugar lumps in a tin box was not as convenient as a packet of glucose, for the tin was fairly heavy and granules of sticky sugar spilled into your pocket from the rattling lumps.

In preparation for my discharge from hospital, my mother had been advised by the consultant to read Dr Lawrence’s text book, The Diabetic Life. It was 230 pages long. She dutifully followed this guidance, reading a chapter each night before going to sleep, including the one on “Operations and Surgical Complications”, which vividly described ulcers, infected bone and amputations! On 16th April, eight weeks and three days after my admission, I left hospital equipped with medical supplies and a small pair of metal scales (Image 8), graduated from a quarter of an ounce to eight ounces. To follow my prescribed diet of 22 Black Lines and 10 Red, I was given a diet card, no bigger than a sheet of foolscap paper. Compared with the literature offered by the dietitians at Alder Hey in the 1980s, the information was rather meagre. Seeking more practical information, my mother went to a bookseller and purchased The Diabetic ABC and The Cookery Book for Diabetics.

Reading the 1955 edition of The Diabetic ABC today is encouraging, as it emphasises the great advances and changes that have been made in the management of diabetes. “Bread, potatoes and alcohol” are included in a list of dangerous foods because “they have a high carbohydrate content.” The paragraph headed Precautions for Motor Driving includes the surprising guidance, “It is not necessary to declare your diabetes when applying for a driving licence.” And included among the rules for general health are the following maxims:

“A satisfactory daily action of the bowels must be secured. Usually the vegetable diet keeps this right. Otherwise mild laxatives, such as senna, cascara, or perhaps salts, should be taken as your doctor advises.”

“A diabetic should have plenty of rest and sleep and lead a life of moderation in all respects. Worry is very bad for diabetics and should be avoided as much as possible.”

It was with this last recommendation in mind that I sought a career in the NHS!

My education in diabetes and its management was indeed minimal, but in hindsight I believe that, for me, learning by experience was more effective and long-lasting. When working as a member of a diabetes management team, I often pondered what my reaction would have been to intense instruction from a group of keen therapists! I suspect I would have been overwhelmed! Despite my consultant’s gloomy predictions, I did work in full-time employment and, more importantly (Image 9), before the end of the Easter Term 1955, I was indeed selected for the under-16s netball team!

Developments that will impact your practice.

7 May 2025